Recent posts

#31

Humor / Re: Humor for the Day

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 17, 2026, 03:21 PM #36

Humor / Re: Humor for the Day

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 17, 2026, 03:19 PM #37

Suspension Setup Strategies for Track & Racing / Re: Suspension Setup Strategie...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 16, 2026, 01:39 PMOther Key Decisions to Make

Tires & Wheels:

One of the most important choices to make are tires & wheels. First, Captain Obvious here, tires are the only thing connecting the race car to the track. They are the #1, most important, highest priority to a race car. Any race car. If you race in a series or class that has tire & wheel rules, other than following them, the only advice I have is always run FRESH tires.

I'm not referring to tread depth. Tire age is key. The rubber in tires begins curing the instant they are poured in a mold & never stop hardening. Running old tires on a race car to "save money" is the dumbest thing you'll ever say. It completely throws away the event. Test, play, fun track day or race, buy & run fresh tires. If you call or text me trying to sort out your hot rod on old tires, I will laugh & hang up on you. Yes. I. Will. No sense in both of us wasting our day.

Now, if you're building a track car, time attack car or race car with no tire rules, it behooves us to run the best tire we can. Best usually, but not always, means highest grip. If you run endurance racing, we need to consider wear & temperature management. Size matters. Typically we want to run the biggest tires we can, but there are exceptions. If you're building a bodied race car that is light and or low powered, tire friction & rolling resistance comes into play.

For road race cars that run 4 cylinder race engines in the 200-300HP range, we run race slicks no wider than 315's. For 400-450HP we'll run 335's rear & 315's front. Yes, an exception to my all 4 tires the same size guideline. Beyond 500HP, & up to 700HP, we'll run 335s all around. Above 700HP I like to run even wider tires. I only run the 345/35-18s when we want the tire to fill up the fenderwell better, like on a stock car. They're taller than I like at 26.8" (with a taller sidewall) ... compared to 335/30-18's at 25.6" with over 1/2" shorter sidewalls.

I LOVE the Hoosier 355/650R18. It's 25.8" tall with 13.50" tread width compared to 12.8" for a 335. Plus the S2 compound is a little faster than the Hoosier "A". I love to run this tire on all 4 corners of race cars, up to about 850-900HP. After that, we see a lap time advantage running the 1" wider tread Hoosier 365/720R18 (14.50" tread). I don't like the 28.20" height of the 365/720R18 for lateral G's, but it does help with initial throttle roll on & corner exit grip with 900HP + race engines.

Rookie Racers often don't know how critical tire width to rim width ratio is to grip. We often see people putting good width tires on narrower than ideal wheels ... usually to suck the sidewalls in for fender clearance ... and experience significantly less grip. An example is when Racers want to put a 315 tire with 11.8" of tread on a 10.5" wheel. Not good.

The optimum wheel width for grip varies with sidewall height & design. Stock Car bias ply tires have 6"-7" sidewalls & respond well to wheels around 10% wider than tread width. Modern cars with 18" wheels & 30 or 35 series radial tires have 3.5"-4" sidewalls & respond well to wheels equal to tread width or 2-3% wider than tread width.

If the rim to tire ratio is narrow, the sidewalls are bulging out past the rim, and we run less tire pressure to achieve even tread wear. This is bad. The lower pressure is not enough to keep the tire carcass in the proper shape with high G side loads (even worse with taller sidewalls). So, the tires "roll under" significantly during cornering. This distorts the tread contact pattern.

This is WHY we have less grip with narrow wheels. Wider wheels require more tire pressure to achieve even tread wear & this keeps the tire carcass in the proper shape with less roll under. A bonus advantage to wider wheels & higher pressures is, the optimum slip angle is lowered. This makes the tire respond quicker to driver input.

For 18" wheels with radials, treaded or slicks, we recommend:

For 315/30-18 tires with 11.8" of Tread, we recommend 11" min, 11.5" is better, 12" is best.

For 335/35-18 tires with 12.7" of Tread, we recommend 12" min, 12.5" is better, 13" is best.

For 345/35-18 tires with 13.2" of Tread, we recommend 12.5" min, 12" is better, 13.5" is best.

Unfortunately, many series rules limit rim size, as they know running wider rims is an advantage. SCCA GT1 limits the 355/650R/18 fronts to 13" & the 365/720R18 rears to 14". They would both benefit grip-wise with ½"to 1" wider rims if you're not racing under SCCA rules.

Trans Am limits the Pirelli 320/660-18 to 13" wheel, which is awesome for the 11.85" tread width. Similar with the 350/720-18. It is limited to a 14" rim & has 13.10" tread width. Great rim to tread width ratio.

I always believed I wanted the lightest wheels to reduce unsprung weight. The goal in running lighter wheels (and other things) was to get the suspension to follow the track undulations the best. The proven, real world objective is to keep the tire loaded over track undulations. This is why 6, 7 & 8-post machines exist. They help pro level race teams figure this out BEFORE going to the track. Later on, I learned wheel rigidity is just as, if not more important than weight.

Believe it or not, I learned this next bit of wisdom kart racing. I was running the lightest spun aluminum wheels (Van-K for you old Kart Guys) and never thought otherwise. A good friend of mine, race car builder extraordinaire Ray Cunningham, suggested some cast magnesium wheels that were heavier but more rigid. Holy crap they had more grip. Better front grip & turn in. Better rear grip. Faster lap times. Yet they were heavier.

I learned in road racing full bodied, tube chassis race cars, with aero, that ultra light wheels flex too much & allow the tire carcass to distort. Not good for the footprint, contact patch or grip. As we put the same tires on stronger (but heavier) wheels we went faster. So, I was on an eternal search for the lightest, strong wheels. Until I ran Forgeline wheels. They have 5 wheel designs that are perfect. They are the best balance of strength, rigidity & lightness.

The factory Porsche teams runs Forgelines & asked them one time to take 3/4 of a pound out of each wheel. Forgeline's engineers told them that's not the way to go. But us racers gotta try stuff ourselves sometimes. Porsche put the lighter wheels on & went slower ... thinking it was some other handling problem. Forgeline suggested they put the regular wheels back on ... and viola ... the handling problems went away & they went quicker. I'm no shill for them. I simply love a well engineered product I can count on. We run nothing else.

Summary, your strategy decision here is easy if you run with tire & wheel rules. Buy the lightest strong, rigid race wheel you can, in the size dictated by the race series rules. If you're not under rules, pick the best tires for your application .... Based on width, grip & rolling resistance ... with the optimum tire width-to-wheel width ratio ... and again ... buy the lightest strong, rigid race wheel you can.

Track Width & Wheelbase:

If you are racing in a series with track width and/or wheelbase rules, I assume you're going to do the follow the rules. They are designed to keep everyone on a level playing field. We won't be, but that's the goal. Whatever the rules are for track width, do NOT make your car narrower for a rules cushion. I push the very limit of their track width rules ... because this is a key factor to corner speed. I'll argue & make them remeasure several times in tech if there is an issue.

Soooo ... if you're running time attack, a track car or racing in a series without track width rules, you have a decision to make. Regardless of body choice, you can always widen the body, widen the fenders or flare the fenders to gain track width. Just know track width is corner speed. Take this into account when you choosing a body.

Most, but not all, silhouette race bodies are super wide right out of the mold. But this is an area I always push. Because it is key to speed, I always ask can we make it wider. Steel OEM shell, custom hand built steel body race car, fiberglass shell or whatever ... if you want to go faster, safely, increase the track width if the rules ... or lack of rules ... allow you too.

Wheelbase used to be a big conversation in full body car racing. Back in the day, when front end geometry had yet to be figured out, running a shorter wheelbase car helped it turn a little better. This was true on road courses & even more so on autocross tracks. I see some feather weight Shelby Cobra racing autocross with a 90" wheelbase & think they should win every event, unless they break.

Today, if you are picking an older race car to race Vintage or as a Track Car, this theory of shorter wheelbase may still apply. It depends if you're running the old, outdated, crappy front end geometry. If that is the case, just know your car model wheelbase choice will matter. On the other hand, if you're building a new chassis with modern, well designed geometry, we find wheelbase is less of an issue.

I didn't say it was a non-issue. Just less. If you're running road courses & your choices include a 105" wheelbase, 110" wheelbase or a 125" wheelbase, I'd suggest avoiding the 125" wheelbase. The other two? Not sure you'll notice if the front end geometry does its job. Personally, for our Track-Warrior cars, I really like 108" wheelbase. It allows us to move the engine back 8.5-9", get a 50/50 weight bias, has plenty of cockpit room for drivers over 6' & the rear suspension links are long enough to see minor change with travel & roll.

Chassis Rigidity:

When you think about it, all chassis are rigid or flexible to some degree. No chassis is 100% ridged with zero flex, and if it is, you built it waaaaaaay too heavy. Rigidity in a chassis makes the car more responsive to driver input & tuning changes & creates more grip. Flexibility in a chassis makes the car less responsive to driver input & tuning changes ... and has less grip. Most production cars are limp noodles & flex way too much.

You can build a chassis too rigid for optimum performance. I'll share my experiences. Designing a car with the optimum rigidity is a balancing act. We all have seen race cars too soft. Too flexible under race loads. These cars are sluggish & slow. They are lazy to respond to Driver input & the handling doesn't change much when significant tuning changes are made. The worst is when the chassis is so "flexi-flyer" the suspension and/or steering move around. These cars are not consistent & teach the Driver bad habits.

We know a more rigid chassis is quick & responsive to driver input. Especially in the suspension & steering area. The car turns in better. It is quick & responsive through switchbacks (chicanes). If the chassis has the correct amount of rigidity in the right places, the car accelerates better & brakes better too. A well designed chassis is confidence inspiring. A chassis that is too flexible ... or too stiff ... can be scary as hell to drive.

Yes, a chassis can be too rigid. I have seen a LOT of race cars overbuilt for the application. I first learned this in the 1980's while we were building drag race doorslammers. The long stroke, 600-700 cubic inch Mountain Motor Pro/Stock cars of that era created so much torque, they would launch & 60' quicker with additional frame structure.

Some called it a "double frame rail." We call it a "backbone" connecting the rear half of the chassis to the front in the trans tunnel area. When the short stroke 500" NHRA Pro/Stock Racers tried this, they slowed down. The additional stiffness actually hurt grip on launch & it showed in the 60' times.

Decades later when I got into USAC Midget racing, I bought a used race car. I could see it was a more rigid design than others. Man that thing was fast! For 10 laps. It was TOO SENSITIVE. As the track would rubber up on a 30-50 lap race, this car's handling would change significantly. We had to decide which 10 laps we wanted that car fastest. LOL

Our biggest competitor in the USAC Midget chassis business had a little trick up his sleeve. I could see the difference between his "House Car" & his customer cars. His cars had additional bracing to be more rigid. When I asked him about it, he grinned & said, "My customers are not constant tuners like you & I are. By making my customer cars softer, the car is less sensitive. It works OK at most tracks & track changes don't affect it as much. I make mine stiffer, which requires being more spot on the setup, but our car is faster."

I design all our race car chassis ... from the autocross cars to the each level of Warrior tube chassis ... knowing exactly where the loads are, and are not, as well as how much G-loads that car & suspension package can create. There are no wasted bars & no extra weight.

I've designed the Track-Pro & Track-Star roll cages a little more flexible than cages in our Race-Pro & Race-Star. Our Track Car clients are less concerned with a few tenths in lap time & want to have a fun, easy day. Our Race Car clients want every ounce of performance & are willing to do the constant tuning it takes to win races & championships. Your choice.

Our 21 Track-Warrior chassis vary in rigidity, depending upon how much power, tire, weight & g-force loads they're designed for. It's not a one-size fits all. The same can be said for our 8 Race-Warrior chassis. They vary from each other based on power, tire, weight & g-force loads. But they are more rigid than our Track-Warriors because our Race Car clients want every ounce of performance & are willing to do the constant tuning it takes to win races & championships.

Knowing where the forces are in a race car is half the battle. I see so many race cars built wrong, built dangerous and/or built overweight for no good reason. By "built wrong" I mean the chassis designer and/or builder created strength where there are no forces ... and left areas weaker, where there are serious high forces.

A great oval track chassis builder out of Los Angeles, Jeff Schrader, owns Racecar Factory in Irwindale. He's a NASCAR ARCA champion crew chief as well. He built chassis for me of my design for a few years. He & I would look at race cars in person or in photos occasionally & just shake our heads. His phrase was, "they bars going from nowhere to nowhere." Hilarious but true.

Often times when someone is building a car doesn't know what the F they're doing, they will overbuild it. X's there. Triangles everywhere. They say, "When in doubt, build it strong." But they end up with a heavy tank that doesn't handle well, isn't fast & is not competitive. It is simply because they don't where the forces are, how much the forces are or how strong it needs to be built for those forces.

I can't teach everyone on here the keys to complete race car design. But I can get you some clarity on do's & don'ts. First some don'ts. Don't build your chassis based on drag cars. Drag car forces are primarily in the rear of the car. When you see a massive jungle gym of tubing back there, it's to deal with the 800HP or 3000HP forces they're trying to manage. Don't build your chassis based off of dirt cars. Dirt cars work primarily off the rear tires. The rear tires are for accelerating, braking & turning. Hell, you can run one of those car without a steering wheel around an oval track if you have experience. Watch this video. It's hilarious. The driver gets hit by another car ... knocks the steering wheel off ... uses the throttle to keep the car turning ... and calmly puts the wheel back on. Go HERE

Pavement Stock Cars & Road Race Cars work off the front tires. The do most of the braking and all of the turning. We pull way more g forces on corner entry under braking than we do accelerating out of the corner. The front end is where you need more bracing for more rigidity. Especially under hard, threshold braking on corner entry.

Under hard braking on corner entry, there is a huge amount of force pushing up on the front tires & therefore the chassis. The front frame literally bows upward. This chassis flex is "lost energy" & reduces the load ... and grip ... on the front tires. Adding strength to the front frame clip ... in the correct path of the forces ... reduces this flex significantly & adds substantial front grip to your race car.

Adding an engine "bay bar structure" to reduce the amount the front frame bows up, reduces this lost grip. Unfortunately, that force is all directed at the spring or coil-over mounts, twisting them inward. Again, this flex is "lost energy" & lost front grip.

The second part of the solution is to strengthen the bay bars on both sides so they can't twist inward. That is what a bay bar brace does. It prevents each side of the frame & cage bars from twisting inward, towards each other. This two part solution restores almost all the lost grip, allowing you to drive in deeper, with more grip, speed, stability & predictability.

Summary, your strategy decisions here are to determine how rigid & strong to make your chassis & where that rigidity & strength needs to be. That starts by determining the future weight of your race car & the loads it will see from g-forces & power. After that you need to decide if your engineering knowledge & experience is enough to design this chassis optimally. Or, should you hire an expert to design it for you. (I don't do this anymore) A 3rd option is if one of my engineered chassis fit your needs, then my race car in a box package will achieve your goals.

Light race cars don't just happen:

A friend & mentor of mine, Louie Gennuso, always said ounces add up to pounds. Louie built & crew chiefed a lot of amazing, winning race cars in the oval track world including Super Modifieds & Indy Cars. He paid attention to every little detail when it came to weight. So, he had the lightest, best handling, fastest, winningest race cars. I would see him shortening the threads on EVERY bolt on the race car, so there were no excess threads. None. Not one thread. Not kidding.

He ran aircraft nyloc half nuts everywhere the bolt was in dual shear. He ran the half nuts on studs in single shear, because they don't move around like a bolt. He only ran full height AN Nyloc nuts on single shear bolts. He ran light AN washers everywhere he could. But he ran bigger, thicker heavier hardware if it was needed for safety or durability. Just zero excess weight

If the team could afford it, he ran titanium bolts. If the budget was a little smaller, he ran tubular chromoly bolts. If they budget was nil, he would be drilling out the centers of larger bolts & deburring the ends. Safety wiring something? After twisting the wire don' leave more than 1/2" tail. Adding a bracket to the race car? Regardless, if it needs to be steel or can be aluminum, use the thickness needed and no more. No excess either. Be that way in the chassis design too. Only run bars that need to be ran for forces that actually exist ... and run the minimum diameter & wall thickness needed.

My belief, and Louie's, is light race cars don't just happen. They are the result of hundreds of ferocious decisions to be light. Light chassis, light suspension, light wheels, light brakes, light body, light engine, etc. We can & did build 2400# complete road race cars with aluminum small blocks. 2500# if iron block.

Why so light, if we have we weigh more anyway? The answer sounds benign but is very, very important. All great race car builders do this. Build the car as light as possible then put the ballast where you need it. In oval track cars, left side ballast is key to more wins than can be counted in history. In road racing, it's ballast low (floor level) & in the center of the car. Building your car this way is a race winning strategy. It doesn't happen by accident. It happens because you made a one big decision ... and a lot of little decisions after that.

Friction:

Friction happens on it's own. It is a choice to reduce friction in your race car. I see newbie racers concerned about how much aerodynamic drag they race car body has, but don't give two hoots about all the friction in the car. My race cars were so low friction one person could push them through the pits. They rolled that easy.

There are lots of areas of friction we care about, including the wheel hubs, brakes, rear end, transmission, engine & engine accessories. There are lots of ways to reduce friction including, micro polished surfaces, coatings, additives, preload adjusters, ceramic bearings, tapered angular bearings & more.

Our USAC Focus Midget weighed 1100# & the sealed spec engines only made 185HP. They were faster than stock cars at most tracks, but we always wanted more power. An alternative is reducing friction. We ran angular contact bearings in hubs & in the rear end. We ran micro polished bearings & gears in the rear end. We'd take a $1300 rear end & make it cost $5500, but it would free up 3HP on the wheel dyno. Maybe not the best cost per HP. LOL. But we were racing to win. Period.

A strategy decision to make is how much you care about reducing friction in your race car. This happens only by choice & lots of little choices along the way that cost money & time. Make the decision if this is important to your race car or not.

Aero:

Aero downforce doesn't just happen either. If you're racing in a series with rules, I assume you're going to do the max legal aero. But if you're running time attack, a track car or racing in a series without aero rules, there are decisions to be made on what, where, how much & can we afford that. I have a whole forum section on aero to explain the what, where & how much. But you have decision to make on how aggressive you want to be.

If you're building a time attack car, I suggest you go balls out. So far the race car looks like a space ship. If you're racing in a series, like NASA Super Unlimited, where there are no aero rules. How far you push for downforce is decision for you to make. Same if you're building a track day race car.

One thing you should take into account is how FICKLE aero downforce can be. This is KEY, aero downforce is not an absolute. Airflow is a variable. If we have a headwind, we'll have more downforce. Tail wind? Less downforce. Crosswind? Who knows! Hang on! A wheel jerking Driver can make downforce disappear long enough to crash.

With significant aero, the Driver HAS TO BE SMOOTH as glass ... or bad stuff will happen. Remember, aero downforce is adding grip on top of the mechanical grip we build into the suspension. There are two common strategies for Track Cars when it comes to aero. One is put significant aero on the car, to add grip for a safety cushion. I love this strategy. Just don't drive to the limits & be a squirrel behind the wheel. Give yourself some cushion.

The second strategy is kind of stupid. Guys say I don't want to add any aero because I don't want to rely on it. WTF? They know they're squirrels behind the wheel & heard aero can be fickle. They don't want to get in over their head & then "lose downforce." I'm not a fan of this strategy. It is marter to have the extra grip & not need it, than to need the extar grip & not have it. I suggest Track Car guys put the aero on they can afford & don't over drive the car.

Grip Creates Harmonics:

Grip creates harmonics. Period. Anytime we create more grip in a race car, we will have more harmonics. Higher spring rates? More harmonics. Higher sway bar rates? More harmonics. Stiffer shock valving to control the springs & bars? More harmonics. Shorter sidewall tires? More harmonics. Wider wheels & more tire pressure? More harmonics. Big aero creating downforce and load on those springs & tires? More harmonics.

Ok. Ok. There are exceptions to the rule. Eliminating chassis bind reduces harmonics. So does eliminating stiction throughout the suspension. But, for the most part, creating race car with a high level of grip, brings a high level of harmonics with it.

Read the following story about Prototype Development Group & shock valving. Then pick up after the story where I cover makign harmonics decisions.

Prototype Development Group Achieves Big Gains with RSRT Valving

The partnership was sparked when PDG reached out to Ridetech for a shock development partnership. Ridetech's Bret Voelkel accepted the proposal and linked the team to work with Ron Sutton. Ron worked up two sets of Fox/Ridetech shocks for them to test. Shortly after, PDG traveled to Buttonwillow Raceway for a test that produced eye-opening results.

"We had customized name brand race shocks and ran into a limit with the shock absorbers ability to control wheel motion," PDG crew chief True Tourtillott said. "I was aware of Ridetech and Ron Sutton's expertise and their commitment to be a market leader. Their product is multiple steps better than anything on the market. I saw the success they were having and it sparked my curiosity in Ron and Ridetech to try to take it to the endurance road racing environment."

On May 27th, the team traveled to California's Buttonwillow Raceway to test their new Fox/Ridetech shocks with Ron's piston & valving package. Buttonwillow Raceway is one of the bumpier tracks on the WERC circuit making it the perfect venue to put a suspension package through its paces. Driver Carl Rydquist was tasked with track testing each shock package the team had brought using one set of tires for an accurate comparison. Rydquist went out and set a baseline time of 1:49.9 with PDG's current shock set-up.

The crew then installed the first set of shocks that Ron Sutton provided them. The Fox/Ridetech Triple Adjustable shocks with "Track-Star" valving. The shocks carry the same valving that Sutton has used for clients in dual purpose autocross & track applications. Carl said the PDG GTM car immediately had more grip with a best lap of 1:46.8, a shocking 3.1 seconds quicker than the baseline package.

"We haven't done of a lot of hardcore, fender-to-fender racing so we were happy to see the results. It was an epic improvement!" Ridetech's Bret Voelkel said. "I would not have predicted that level of improvement. It is almost unheard of and really promising."

Excited by the progress PDG moved on to the second set of Ridetech Triple Adjustable shocks that had been provided to them. This set of shocks carried RSRT's "Race-Star" valving and the performance was even more impressive. The car gained another four tenths of a second for a total best lap of 1:46.8. PDG had gained 3.5 seconds a lap in time simply by changing to Fox/Ridetech shocks with Ron Sutton valving.

"The Fox/Ridetech solution has every bit of the performance of a high end race shock at a price impossible to beat for a triple adjustable American-made product. The additional value also comes from the support that Ron provides. We couldn't be more pleased," Tourtillott said.

Although Sutton provided the advice and the product, he too was pleasantly surprised by the amount of gains that PDG experienced.

"There are a lot of name brand shocks out there, with long histories, that are simply behind the technology curve," Sutton said. "I knew the Fox/Ridetech shocks with my valving would outperform the brand they had. Buy even I was surprised that the shocks went 3.1 seconds faster, then 3.5 seconds faster, in a winning GT car & on a rough track. People always ask me how much faster these shocks would be. I couldn't quantify it before. Here we had a proven car, with a good set-up and a consistent driver with great feedback. Now we know how much quicker there are."

It was a benchmark day for all parties involved that had them encouraged for their future. Prototype Development Group has a laser sharp focus to go for the 25 Hours of Thunderhill overall win. That victory seems much more within their grasp with the improvements they have seen with Ridetech.

"It was not just about lap time, but that the driver has control of all four tires," Tourtillott said. "In endurance racing with multiple classes, the ability to drive anywhere with confidence while passing five to ten cars a lap is huge. It is critical to be able to go off line and off camber."

At the time, PDG was racing in NASA's Western Endurance Racing Series Championship & had fallen close to 3 seconds behind an IMSA level Porsche GT race car. After the test, PDG & Carl Rydquist went on to win more WERC races & that season's championship.

Bouyed with their newfound speed, they decided to tackle racing the top GT class of the United States Touring Car Championship. More wins & the USTCC championship followed. They backed it up the following year with more GT Class wins & a second USTCC Championship.

With the Trans Am series expanding to the West Coast, PDG & Carl Rydquist entered the series in SGT class. Results? More wins & the Trans Am SGT West Championship.

OK. Story Over. Back at the Ranch ... the veteran driver, Carl Rydquist, mentioned the increased harmonics from all the additional grip to the team to discuss. He loved the grip. He races to win & the harmonics didn't bother him.

This is not comfortable in the car. In fact, it is downright uncomfortable & will wear out the average driver in a shorter time. If the goal is to build a winning race car, the driver & crew need to embrace harmonics as a side effect of going faster. The driver needs to be in better shape & not complain about the harmonics to the crew. Because the only cure is to reduce grip & slow the car down.

Now, if you have a track car, and driving is all about fun, you need to decide what level of harmonics are you willing to live with to outrun all of your friends. Thank goodness track days only run 5-15 laps, then you get a break.

But Carl sure noticed. His concern is when they run the 25 hours NASA races once a year with two additional drivers. "Gentlemen Drivers" as they're known. Fellas that drive good & bring a check to help fund the race event. His concern, as they are older, they may not be able to handle the increased harmonics for hours at a time.

The good news, by doing it with shocks, is they can reduce the harmonics, by reducing the grip, with an adjustmanet knob on each shock. So they can decide if & when they want additional grip & can handle the additional harmonics. When they come in for a driver change, adjust the rebound softer on 4 shocks is pretty quick. Again, with doing this on the shocks, they are in control of the grip & harmonics. If it was monster sway bars & stiff springs, that is not a quick change in the pits.

Racers, I know your choice. Do everything to win. But for Track Cars, & you Track Day racers, you have choices to make. How mean do you get with the Sway Bars & springs? How mean do you get with the aero? How mean do you get with the shocks. Shocks are the quickest & easiest to "tame" if you want to. Plus quick & easy to put back & go outrun some "friend" that has been runnning his mouth faster than his car. You know the guy.

Safety:

Borrowing from a few things I've said above, "Safety doesn't happen on it's own." So many racers gloss over this area. They think of safety as the driver's suit, helmet & harness. It is so much more. PLEASE read my forum thread on Safety. Realize safety is designed in at the beginning, or it's a reckless afterthought.

In building a new car, you have decisions to make on many components. A lot of our focus is on "go fast." Some of our focus needs to be on "prevent crashes" & "survive to race another day." I find wheel hubs are the most overlooked. You'll learn about hub bearing ratings & more in the Safety forum thread. Same can be said about building in crush zones in the chassis structure. Often overlooked.

Fire systems & suit choice based on TPP rating are critical decisions to be made. Full containment seats don't get enough love. They have saved as many lives as HANS devices. Maybe more. I suggest you choose a racing seat with full containment & plan to run a HANS type device from the start.

I find Track Day racers are the most lax on safety. They somehow think, "well I'm not really racing." But your car breaking & crashing can happen just as easy as in a race. Someone losing control of their car & spinning in front of you can happen just as easy as in a race. You crashing into another car or barrier can happen just as easy as in a race. Someone else's car breaks or they lose control & take you out can happen just as easy as in a race. A component failure & in-car fire can happen just as easy as in a race.

Alright, I'll get off my soapbox. Sort of. If you don't take the lead on your race car (or track car) safety, who will? No one. I strongly urge you two things:

1. Don't rely on the rules or requirements of sanctioning bodies to guide how safe you make your car & gear. Many tracks & sanctioning bodies want to keep the rules simple to attract new customers, while doing just enough to cover their ass with the insurance company. Make your own safety a priority & go above what the rules require.

2. Learn about safety as passionately as you learn about going fast. Create your own safety standard. In all my race cars I maed the rules my Drivers had to follow to protect them. The last thing I wanted to happen is someone to become serious hurt, paralyzed or die in one of my race cars because we were lax. I required full containment seats when the rules didn't. I required HANS devices when the rules didn't. I required Nomex underwear, gloves & socks when the rules didn't. I required a higher TPP fire rating than the rules did. You get the picture.

I call this safety advice my "Client retention program." If you avoid crashes due to a better built car, you might stay a client longer. If you survive crashes due to smart safety decisions now, you might stay a client longer. If you survive a hard crash due to crush zones in the chassis, you might stay a client longer. Because I'm sure if you die I'm losing a friend & a client. Neither of us want that.

#38

Suspension Setup Strategies for Track & Racing / Re: Suspension Setup Strategie...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 16, 2026, 01:38 PMAdditional Decisions to Make Once Your Suspension Strategy is Set

Front Clip & Crossmember:

• Now is the time to design in proper front clip & crossmember height for ground clearance.

• Ride height & adjustability range.

• Same with making sure the front suspension itself has proper travel clearances.

• No issues with tie rod or sway bar interference through travel & roll.

• Suspension travel capacity without bind (control arms, spindle, ball joint angles, shock mounting, etc).

• You can also place the mounting heights of all the control arms at the optimum heights.

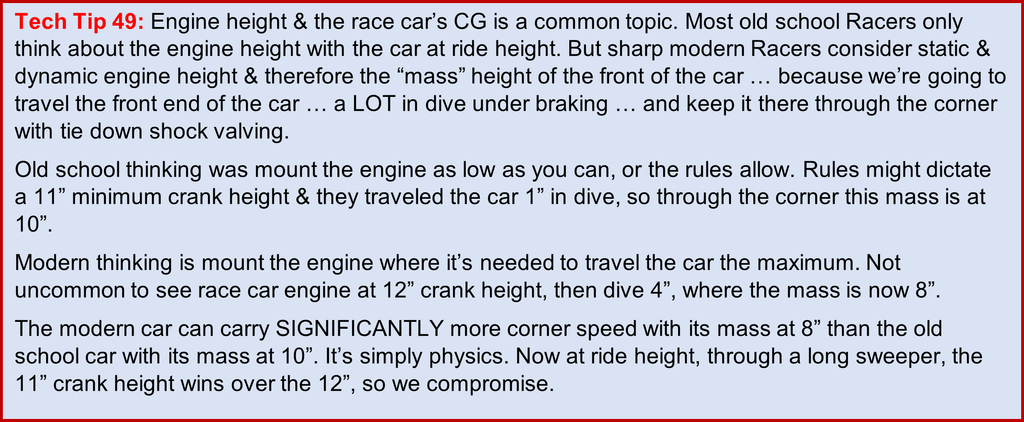

Engine Placement:

• If you're going Low to Moderate Travel, you'll want to mount the engine as low as rules allow and/or you have oil pan clearance, typically below the bottom of the clip crossmember.

• If you're going High to Ultra High Travel, you'll want to mount the engine high enough to provide adequate oil pan clearance, typically above the bottom of the clip crossmember.

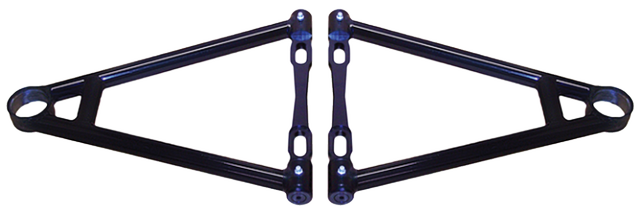

Control Arm Lengths:

If you chose a low travel setup, achieving enough camber gain can be a challenge. And if you chose high travel preventing too much camber gain can be a challenge. The proper control arm lengths are key to achieving the goal.

• If you're going Low Travel, you'll need very short control arms to generate more camber gain.

• If you're going Moderate Travel, you'll need short control arms to generate more camber gain.

• If you're going High Travel, you'll need long control arms to generate less camber gain.

• If you're going Ultra High Travel, you'll need very long control arms to generate less camber gain.

Sway Bars & Arms:

• If you have made a travel strategy decision, that will affect the sway bar package you decide to go with in the front.

• If you're going Low to Moderate Travel, you'll run a lower rate front sway bar. This allows you run less expensive, smaller OD, splined sway bars. And, because your dive travel is low, you can run shorter sway bar arms without having too much angle change for the sway bar links.

• If you're going High to Ultra High Travel, you'll need long sway bar arms to avoid having too much angle change for the sway bar links. Longer arms require a larger OD bar to achieve the same rate as shorter arms. Plus you'll want an even higher roll bar rate to achieve your low roll strategy. These longer arm & bigger bar packages do cost more.

Oil System & Pan:

• Part of the Engine Placement decisions are based on oil pan depth. Dry sump oiling systems are almost always better & safer for your engine than wet sump systems in high g-force environments.

• If you're going High to Ultra High Travel, there are also handling advantages to running a short depth dry sump pan. You'll want to get the engine as low to the ground as possible primarily in dive dynamically & secondarily at static ride height.

• If you're going Low to Moderate Travel, you'll have more ground clearance in dive dynamically, so the choice of oiling system is primarily budget & engine safety.

FLLD Target:

• If you have made a travel strategy decision based on your track usage & goals, such as going autocross or road racing, you may be able to work out your Front Lateral Load Target (for Balance) as well.

a. Front Weight bias % + 3% for tight autocross tracks

b. Front Weight bias % + 3.5% for avg autocross tracks

c. Front Weight bias % + 4% for big, open autocross tracks

d. Front Weight bias % + 5% for average road courses

e. Front Weight bias % + 6% for road courses with super fast, sweeping corners

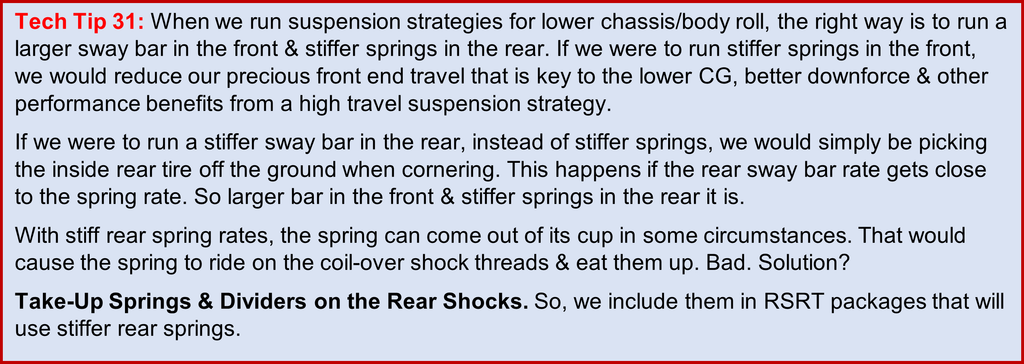

Stiff Rear Spring Strategy:

Now I'm going to throw a curve ball at you. This is an option for the low-roll suspension strategy. You already know we run bigger front sway bars. The "meaner" the set-up ... and lower the target roll angle ... the larger the front sway bar is ... to reduce the roll angle in front. For the rear, a high rate sway bar

won't work. Anytime the rear sway bar gets too close in rate to the rear springs, the bar lifts the inside rear tire off the ground. Literally.

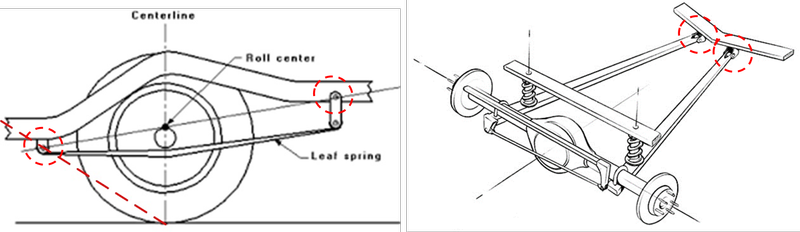

What works pretty well is having a very adjustable rear sway bar set up, like my RSRT versions with 4 holes 3/4" apart, with the highest rate 55%-60% of the spring rate. If you read in the forum section called "Track Tuning Techniques for Overall Handling Balance" you know how much I love utilizing the rear sway bar as a tool handling balance mid-corner. We just can't get carried away with rate. If the rear springs are 300#, I like the stiffest rear sway bar rate to be 180# or less. Remember, we want to reduce the loading of the inside rear tire mid-corner ... to achieve neutral handling balance. But we don't want to fully unload .. and lift ... the inside rear tire. No sir. Huh-uh. Notta. Nope.

If you choose the low roll strategy & increase the front roll stiffness, you need to increase rear roll resistance to match, or we end up with the problem of having diagonal roll the wrong way, from inside front tire to outside rear tire. You have too good options in the rear. One is soft springs with a higher rear roll center & the second is stiffer rear springs with a lower rear roll center. Ideally, with the appropriate rear sway bar.

How high? Higher than my mind could comprehend the first time I was taught this strategy. I have a story for you. I hired a NASCAR Busch crew chief to learn some things from. Rented the track, flew him out, had 2 race cars & crew to test. We tested with front spring rates, different bump stops & even coil-bind setups in search of some lap time. Found it. Both race cars got quicker throughout the day with changes. In fact, we finished testing everything on our agenda early.

That is when this NASCAR Busch crew chief said he'd like to try some things in the rear if I was open to it. Sure! Heck yeah! You know it! Then he said, "Do you trust me?" I thought that was a weird thing to ask after a day of testing. Good testing. Sure I do. Of course. He went up in our Cup Hauler & started going through springs, looking for a certain rate. I told him he was in the wrong drawer. Those are front spring rates. But he grabbed a pair of 600# springs & headed for the car.

I was like ... hey there ... whacha doin'? Again, he asked if I trust him. Ahhh ... yeah. But ... those are 600# front springs. We were running a set-up with rear springs around the 275# range. When the NASCAR Busch crew chief I was working with said we were going to run 600# rear springs ... it fried my brain. First I thought he was nuts or high. If the car is "loose" with 300# rear springs ... what will it do with 600# rear springs? I said, "This is crazy. It will just spin out. It won't have any grip."

But it was the end of a test day, and we were there to test, so I said "sure" ... and warned my veteran, winning race car driver that this car may feel like driving on ice & to "be careful." We had a race to run in a few days. I asked him to just "sneak up on it." He did. Started off 70% and worked his way up faster each lap. By the end of the session, the car was measurable faster than a few minutes earlier. Same car. Same driver. Same track. 600# rear springs. Hmmm.

The car rolled back into the pits after the run. I looked in the window & asked my Driver if he felt the car was faster through the corners even though it had less grip on exit? He said, "it had MORE rear grip on exit. In fact, the car had more grip on all 4 tires." The data acquisition & lap times on the stopwatch all matched. My brain was officially fried at this point. With my 20+ years of racing background (then) it didn't make sense. If the race car was good with 275# rear springs, a little loose when we tested 300# springs earlier in the day ... how could it have more rear grip, more total grip ... with 600# rear springs?

Our test day was over. We went to dinner & beers afterwards. I asked him to explain it & he did. The explanation kind of made sense. Kind of. I struggled to wrap my head around it. So I arranged for him to stay another day, moved his flights & rented the track for the next day, to test this "new strategy"

We went back to the track the next day with the same set-up intact ... with 600# rear springs ... and similar weather (California). Car ran great. As a controlled test ... with full data acquisition & a team of Engineers ... we went down on rear spring rate in steps. The results were:

Session #2: 500# rear springs = Less grip / A little loose

Session #3: 400# rear springs = Crazy loose / Undrivable

Session #4: 350# rear springs = Pretty loose / Not raceable

Session #5: 300# rear springs = More grip / Just a tick free

Session #6: 275# rear springs = Good grip again / Not as good as the 600# springs

Session #7: 600# rear springs = Good grip again / Better grip than the 275# springs

Monitoring the tire temps (infrared sensors behind the tires) showed the concept he explained clearly ... and I got it. I want you to "get it" too. Here is what happened with the tire temps.

Session #1: 600# rear springs = Inner Tire Temp Avg 177° / Outer Tire Temp Average 184°

Session #2: 500# rear springs = Inner Tire Temp Avg 167° / Outer Tire Temp Average 180°

Session #3: 400# rear springs = Inner Tire Temp Avg 147° / Outer Tire Temp Average 168°

Session #4: 350# rear springs = Inner Tire Temp Avg 151° / Outer Tire Temp Average 177°

Session #5: 300# rear springs = Inner Tire Temp Avg 135° / Outer Tire Temp Average 183°

Session #6: 275# rear springs = Inner Tire Temp Avg 124° / Outer Tire Temp Average 191°

Session #7: 600# rear springs = Inner Tire Temp Avg 177° / Outer Tire Temp Average 184°

Again, do your best to visualize what is actually happening in the car "dynamically" mid-corner & exit ... and your understanding can move to a higher level. When the car had 275# rear springs the outside rear tire was loaded just enough for good grip throughout the corner ... and no more. The inside rear tire was, for all intents & purposes, loaded very little during the roll through zone of the corner ... and loaded more on corner exit under throttle. Combined, the grip of both tires was good.

When the crew put 600# rear springs on the car ... the outside rear tire was loaded less (but only a little bit) than it had been & the inside rear tire was loaded a LOT more than it had been ... but combined, they provided a HIGHER amount of total grip through the corner.

Here's the bonus. The outside rear spring (being 600#) helped keep the inside front tire PINNED & LOADED throughout the corner. No matter what direction, the inside tires were loaded more (shown by increased tire temps). This is how the car had more total grip, not just more rear grip. Frankly, had it had ONLY more rear grip, the car would have gotten tight/pushy & slowed down. When, in fact, it got quicker lap times. As the driver said, the total grip improved with the stiffer rear springs.

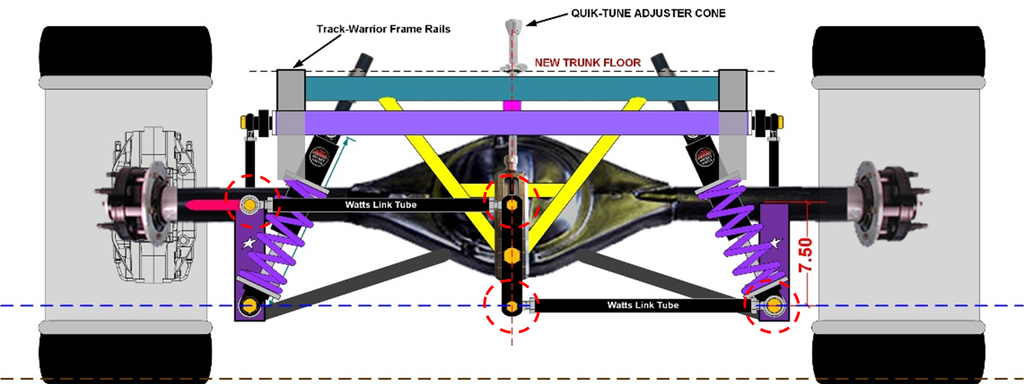

Now, I left something out of the conversation so far, that we'll address now. Rear roll center height. As you probably know I like panhard bars because I can load them left or right to favor tracks with corners predominantly one direction. We adjusted the rear roll center evenly every session.

Session #1: 600# rear springs = 8.00", 8.25" & 8.50" > 8.25" Best

Session #2: 500# rear springs = Tried 8.25", 7.50" & 9.00" > Not Happy Anywhere > 8.25" Best

Session #3: 400# rear springs = Tried 9.00", 8.00" & 10.00" > Crazy Loose in All 3 Settings

Session #4: 350# rear springs = 10.00", 9.25" & 10.75" > Pretty Loose in all 3 > 10.00" Best

Session #5: 300# rear springs = 10.75", 10.25" & 11.25" > 10.75" Best

Session #6: 275# rear springs = 11.25", 11.50", 11.00" & 10.75" > 11.00" Best

Session #7: 600# rear springs = 9.50", 9.00" & 8.50" > 8.50" Best

Conclusion 1: Even though the soft rear spring with high rear roll center is "Close" in performance to the stiff rear spring & lower rear roll center ... the stiff spring/low roll center combination is faster. I have had it proven to me & others many times in ABA tests. I've seen it on other cars I had nothing to do with in both oval track & road racing.

In 20+/- years I have utilized this "Stiff Spring Strategy" on hundreds of race cars. There are two sweet spots or ranges for rear spring rate & a dead zone. One ... the lower "soft spring" range ... is based on working the outside rear tire primarily. The second higher range ... is based on working both rear tires closer to even. When we combine this with a big sway bar set-up in the front ... that works both front tires more evenly that conventional set-ups ... we have a package that works ALL 4 tires better.

Conclusion 2: There are two sweet spot ranges for rear spring rates & a "dead zone" in between. It is affected by the car's weight, but it's more or less 200# in-between the two sweet spots. From experience I find for cars in the 2500#-2800# range, the soft spring sweet spot is 175# to 275# ... the dead zone is 300# to 475# ... the stiff spring sweet spot range is 500# to 650#. For cars in the 3000#-3500# zone, the soft spring sweet spot is 225# to 350# ... the dead zone is 375# to 575# ... the stiff spring sweet spot range is 650# to 800#. Treat this just as a guideline & do your own testing.

The car has more total grip, is faster through the corners, easier to drive, way more consistent on long runs. All modern race cars in top professional series run a low roll strategy today. No teams are on a high roll set-up. They wouldn't qualify for the field at the top levels of racing. At the grassroots level of sportsman racing & competitions like autocross & track events, high roll set-ups are still the norm, but low roll set-ups are "trickling down" from the pro level to grassroots level.

Reminder: With low travel/high roll setups, utilizing stiff front springs, running the stiff spring strategy is not a great option. The stiff rear springs reduce the roll. If all four springs are stiff the car doesn't want to roll or pitch. So, it kind of skates on the top. This works better if we're lower to the ground, with low CG. But not so great with a significant ride height & higher CG.

With high travel/low roll setups, you have the option of running either soft rear springs with a higher rear roll center ... or the stiff rear spring strategy with the lower rear roll center. The stiff spring strategy is faster, but not without disadvantages. With stiff rear springs, drivers need to crack the throttle softer & then can roll it on relatively aggressively. We do not want to "shock" the rear tires with stiff springs, as they will break loose. Once that happens & they heat up, it's hard to get back to good rear grip.

Softer rear springs absorb some of the shock of a driver aggressive at jumping on the throttle. So, know yourself or your driver & use that in the decision. Another disadvantage is the stiff rear spring strategy does not like rough tracks. Slightly bumpy is fine. Undulations in the track surface are fine. It will still be faster. But I've seen autocross courses where the competitors are driving across a drainage ditch. That's not a good environment for the stiff rear spring strategy.

Let's Move On to other Choices you Need to Make Decisions On

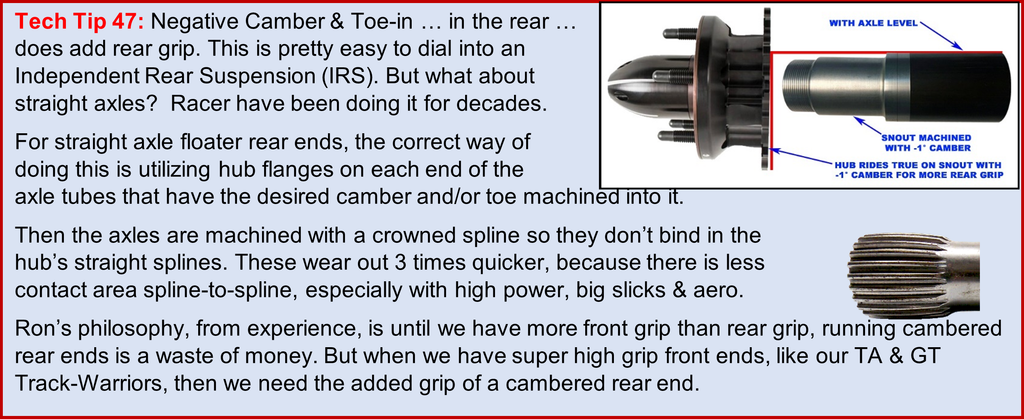

Cambered Rear End?

Negative camber of the rear tires ... in small amounts ... would help the outside rear tire run with a flatter contact patch, giving it more grip. Just as in the front end, camber helps the contact patch of the outside tire & hurts the contact patch of the inside tire, by tipping it the wrong direction. But the loss is not a "1-for-1" kind of thing.

The outside rear tire is loaded more, so it "rolls under" more than the inside rear tire. If you add just enough negative camber to the rear tires to optimize the outside rear tire's contact patch ... you won't hurt the contact patch & grip of the inside rear tire very much. The gain in grip on the outside rear tire will exceed the loss of grip on the inside rear tire, netting an overall grip increase. Besides ... you need to disengage the inside rear tire to a degree anyway, to get the car to turn.

This makes sense, providing you feel you need more rear tire grip. In my experience, with adjustable rear suspensions, on MOST race cars, I've never been in a situation where I couldn't get all the rear grip we needed. There are exceptions. With ultra high grip front suspensions, dialed in perfectly, I have found we can benefit from the extra rea grip a cambered rear end offers. So, the question is not will it help rear grip ... it will. The question is do we need more rear grip?

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2. Toe-in of the rear tires ... takes the outside rear tire (in whatever corner) & turns it "inward" to add slip angle. This makes the outside rear tire have grip sooner & respond quicker on corner entry. This is quite common in road racing, as it builds confidence in the driver. But there are many negative side effects. In my opinion, the side effects are not worth it.

Side effects:

a. The outside rear tire gets to the optimum slip angle at a lower corner speed, reducing that tire's ultimate corner speed capability.

b. The toe-in of the two rear tires ... say 1° each for a total of 2° toe-in ... creates unwanted scrubbing of the rear tires. This builds heat, misleading the crew into thinking they're working the rear tires better.

c. The poor inside rear tire is turned the opposite direction for optimum slip angle, and therefore has less grip throughout every section of the corner.

d. Toe-in of the rear tires reduces the rear steer effect of slip angle. That rear steer effect is needed to offset the counter steer effect the slip angle produces in the front end. So, we end up with a tighter race car ... prone to pushing & understeer. I feel rear toe-in is a band-aid for old design, tall sidewall tires and/or cars with a rear heavy weight bias that need additional grip on corner entry

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

3. Toe-out of the rear tires ... takes the outside rear tire (in whatever corner) & turns it "outward" to reduce slip angle. This makes the outside rear tire have grip later & respond later ... so the car may feel loose on entry. But the outside rear tire gets to the optimum slip angle at a higher corner speed, increasing that tire's ultimate corner speed capability.

The inside rear tire is turned the correct direction for optimum slip angle, and therefore has more grip throughout every section of the corner. Now both tires have more grip & the capability for the back end of the car to carry more corner speed ... if the front is also capable. But the biggest effect toe-out of the rear tires produces ... is increased rear steer effect of slip angle. This increased rear steer effect makes the car turn better ... to help offset the counter steer effect the slip angle produces in the front end.

There are concerns:

a. The toe-out of the two rear tires ... say 1° each for a total of 2° toe-out ... creates unwanted scrubbing of the rear tires. This builds heat, misleading the crew into thinking they're working the rear tires better. It builds heat on the inner edges of the rear tires, clouding the picture of whether the team is properly working the contact patch correctly in the corners.

b. The car does feel looser on initial corner turn in.

c. The extra rear tire grip balances out the rear steer effect ... otherwise the additional rear tire grip is not needed, nor a benefit.

d. It is debatable whether the increased rear steer effect is needed, unless the parameters of the car make it hard to optimize the front suspension & geometry.

Where it may be an advantage & make sense, is long wheelbase, front heavy race cars ... as long as the driver can get comfortable with the loose feeling on initial corner turn in. It's scary at first.

Opinion:

I have a lot of tricks I use in building winning cars. For oval track, especially with the funky weight bias & scrub radius we end up with ... rear tire camber & toe out make a lot of sense. For hardcore track cars running road courses and/or AutoX ... I don't see the gain amounting to much, unless you're tracking a real front heavy and/or long wheelbase car.

Summary:

There are advantages, side effects & concerns ... just like most things. If you have a real need to utilize one of these tuning tools, hopefully you now understand them a bit better & can proceed.

Test:

If you're not sure ... are intrigued ... and have the resources ... set up your rear end with switchable hub plates ... buy a set of square mounts & 1-2 different angle mounts and go track test. In this case, I would start with a set of 1.5° hubs & rotate them to provide 1° of negative camber & .5° of toe-out ... and compare that to the square mounts. Of course, I think this test should come after you have worked out the car many, many days on track & have it pretty dialed in.

#39

Suspension Setup Strategies for Track & Racing / Re: Suspension Setup Strategie...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 16, 2026, 01:38 PMOKAY ... Let's Talk Suspension Setup Strategies

First, all 16 Critical Race Car Design Concepts above matter here, but the red ones matter more as we discuss suspension setup strategies. We're going to pull from many of the Critical Race Car Design Concepts to cover this topic. Chassis roll & dive will be front & center in early discussions. But we'll cover all the strategy areas & options you'll want to make decisions on. Buckle up Buttercup !

Definition of Choices:

A range of possibilities from which one or more may be selected.

Definition of Choice:

An act of selecting, or making a decision, when faced with two or more possibilities.

Definition of Decision:

A conclusion reached after consideration.

Definition of Planning:

The process of deciding on choices, steps & timeline, regarding the activities required to achieve a desired goal.

Definition of Strategy:

A comprehensive plan, or set of integrated decisions, deigned to achieve specific, long term goals or outcomes, by allocating resources effectively & creating a valuable position in a competitive environment.

Discussion:

Not to be funny, but in building race cars, you have a lot of choices, in many areas. Just like you have many choices to choose from in engines, transmissions, seats, helmets, etc. ... you have many choices in the key areas of chassis design, front suspension, rear suspension, overall suspension strategy, etc.

In the forum thread, I'll walk your through come areas of choices, along with providing you pros & cons, to assist you in making informed decisions. As you make these decisions, you are planning. When you pull them all together, you have a comprehensive race car strategy. That is my goal for you.

Let's get going!

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

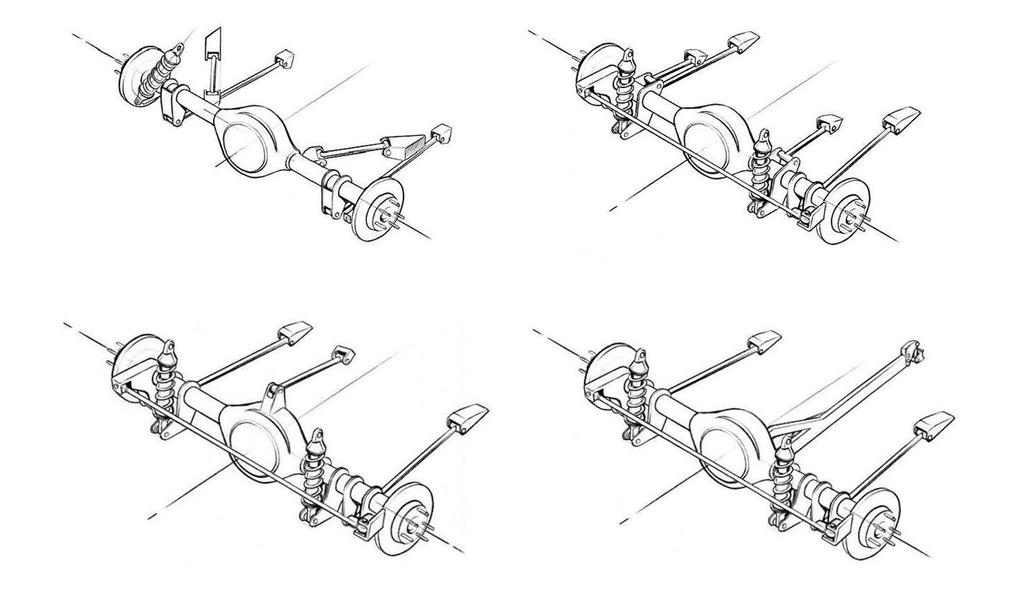

All handling cars need to travel the suspension to work / What's your strategy?

The race car can't run flat ... it needs to travel ... so it's either got to Roll, Pitch or some combination of both ... that's the primary differences in the tuning concepts I'll outline. There are two common strategies that work. One relies more on the roll angle & the other on pitch angle.

Everything we discuss here is for Race Cars with some significant ride height from 1.5" to 6". None of this discussion is for Race Cars that have no ride height rule & run 1/4" off the ground.

Roll Angle vs Pitch Angle:

• A race car should not pitch AND roll a LOT ... it would be dangerous & undrivable

• A race car should not pitch AND roll NONE ... running too flat would make it just skate on

the road surface.

• A competition car can pitch a lot & roll a little ... OR ... pitch a little & roll a lot

You need to pick a path ... so here is what they look like.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Conventional Setup:

• Stiff front springs & soft rear springs

• Small, soft rate sway bars front & rear (if any in rear)

• Higher Roll Angle when cornering

• Less Pitch Angle Change in dive under braking

Old School – Let it Roll:

• High Roll Angle (2° to 3° or more)

• Front suspension doesn't compress much on corner entry. (1" +/-)

• Work the outside tires for grip & work the inside tires less so it will turn.

Disadvantages:

• Too much roll angle overworks the outside tires in corners & underworks the inside tires.

• The tires heat up quick & go away quick, making this a short run set-up.

• After tires "come in" the car is "knife edgy" to drive.

• Very line sensitive ... drivers say, "can't drive it just anywhere" ... meaning it handles poorly out of

its optimum groove.

• As the track grip increases & the car rolls more ... these problems magnify.

• When it rolls a lot & you brake hard, the inside rear tire has no grip. To prevent from being

loose on entry you must run stiffer front springs.

• The stiffer front springs make the car tight/pushy in the middle ... requiring the driver to brake

more and run slower corner speeds.

Advantages:

• The tires heat up quicker, making this a good short run set-up.

• The stiffer front springs allow this race car to be driven deeper & brake harder on corner entry.

• The low travel does not change control arm angles, geometry or camber very much.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Modern Setup:

• Soft front springs & stiff rear springs

• Big, stiff sway bar in front & small sway bar in rear

• Known as SS/BB ... soft spring/big bar ... if no bump stop or coil bind is utilized

• Same concept used in conjunction with travel stops: Bump Stops or Coil Bind

• Lower Roll Angle when cornering

• More Pitch Angle Change in dive under braking

New School – Nose on the ground & run the car flatter:

• Minimal roll angle, controlled primarily by the front sway bar & stiffer rear suspension. (0.5° to 1°)

• Front suspension travels a LOT in dive (compression) creating more forward load transfer & grip on front tires. (3"+)

• Load the outside tires only slightly more than inside corners for optimum 4 tire corner grip.

Disadvantages:

• Even when optimized ... it still can not be driven as deep on corner entry as a conventional set up.

• When racing door-to-door in a field of race cars running a mixture of set-ups, the SS/BB set-up is

susceptible to dive bomb passes.

Advantages:

• Flatter Roll Angle works the tires more evenly.

• The tires heat up slower & last longer ... making a better long run set-up as the tires are "good"

way longer.

• Less line sensitive ... drivers say, "I can drive it just anywhere" ... meaning any line on the track.

• As the track grip increases ... the advantages show more.

• The soft spring/high travel front end puts creates maximum grip on front tires for highest cornering

speeds.

• Will produce faster cornering speeds & quicker lap times over conventional set-up, all other things

being optimum & equal.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The two successful types of suspensions ... conventional stiff front spring/small sway bar - low

travel/high roll ... and modern soft front spring/big sway bar - high travel/low roll ... have been used

successfully at all types of tracks from AutoX to Laguna to Daytona. They are just different strategies

to travel the suspension. The conventional relies on more roll, & the modern relies on more front

suspension dive travel.

There is a third successful strategy ... which is to run a set-up somewhere in-between. Often

referred to as 'tweener set-ups or moderate set-ups, because they utilize moderate front end travel

(2" +/-) & moderate roll angle (1° to 2°).

I used the term "have been used successfully" ... because the conventional strategy hasn't been

used in the top levels of Indy, F1, NASCAR, IMSA, etc. for many, many years ... on any

track ... big or small. At least not by any front running teams. They all are on the modern strategy of

low roll angle. How much they travel the front end depends on the ride height rules of each series.

They are all getting the nose on the ground during dive, if the rules allow.

Where old school conventional strategies are still common is the lower ranks of racing from AutoX, grassroots road racing to short oval tracks. But the change is happening there too currently. I

see it. There is a trickle down process of knowledge. Eventually a racer in each series tests & works

out a modern suspension for their car ... and wins ... and slowly the evolution happens. As with any

change, there is resistance by some people, and acceptance by others. This migration to the new

strategy takes time ... years in fact. Again, I've seen it firsthand.

The cars you have seen run so well with old school conventional set ups are using the first

strategy, have it worked it all out & fine tuned it to its optimum. It wouldn't be as fast as a car with a

modern high travel/low roll suspension that was also worked all out & fine tuned it to its optimum ...

but it would faster than those that aren't optimized & equal.

To summarize, you can make either the conventional or modern set-up work on all types of

tracks. If each suspension is well designed & tuned to its optimum, the modern set-up will carry

more corner speed & provide a slight competitive advantage.

Weight transfer: Speaking literally ... weight doesn't transfer. I mean weight doesn't unbolt itself

and move around the car, re-attaching itself somewhere else just because you jumped on the brakes

... I mean other than your coffee cup. What is really happening is the car's weight mass at the CG is acting on the roll & pivot axis of the car and applying "Force" when the driver tries to get the car to stop, turn or accelerate. Calling it "weight transfer" is simple & easier for many to understand. I'll understand if you use that term. I used to use that term. Today, I use the more proper term of "load transfer" ... which comes from the g forces acting on car's weight mass at the Race Cars' Center of Gravity.

Static Weight & Load transfer (Force) combine to define the load on the car's 4 tires. Load

applied to a tire ... adds grip to that tire. More load equals more grip ... up to the point of overloading

the tire. Overloading & loss of grip happens when the tire exceeds it's slip angle grip range. We'll cover a LOT MORE on this soon.

As load shifts from one tire, we are reducing the load on another tire. Understanding this is key. Whatever you car weighs ... 2500#, 3000#, 3500#, whatever ... that's what you have to work with ...

and only that to work with.

With the exception of aerodynamics ... suspension components & geometry tuning are the

primary tools we have to work with in controlling load transfer from tire(s) to tire(s).

Reminder: You're not creating the Force. The Force already exists when you try to stop, turn or

accelerate the race car. When you step on the brakes, Force will make the front end want to

compress (dive) & the back end want to lift ... also known as "pitch.". You're just using the tuning

tools available to influence how fast & how far the front end dives & the rear end lifts. When you

steer the car hard left or right ... Force will make the car roll about its roll centers. You're just using

the tuning tools available to influence how fast & how far the car rolls. On corner exit, under power

... you get it.

We have many tools to use, to influence chassis pitch & roll, including springs, sway bars, shocks,

adjustable roll centers, weight placement, ride height, suspension arm or link geometry, track width,

wheel base, etc, etc. Some are "built in" & some are tunable. For this section I'm focused on springs,

sway bars & shocks.

Captain Obvious says:

• When you brake in a straight line load transfers from both rear tires to both front tires.

• When you brake & turn at the same time, load primarily transfers from the inside rear tire to the outside front tire.

• When you are turning, with no braking force, load is transferring from the inside tires to the outside tires.

• As you accelerate out of the corner, load transfers primarily from the outside front corner to the inside rear corner.

• As you unwind the steering wheel to straighten the car, but are still accelerating, load transfer is from the front tires to the rear tires.

This next part is instrumental in understanding your role as a tuner. Where load is

transferring TO ... is loading the tire more ... and increasing tire grip/traction at that tire. Where ever

load is transferring FROM ... is loading that tire less ... and decreasing tire grip/traction at that tire.

You need to optimize the "balance of the grip" of all 4 tires at each stage of the corner (entry-middle-

exit). You don't want to over load some tire(s) & underload other tire(s). You're tuning the

car to find the optimum "balance of the grip." To learn more on this, go to the "Track Tuning Techniques for Overall Handling Balance" section of the forums.

Captain Obvious Back Again:

Tires are your only contact with the pavement. Grip is speed. Using all four tires will be faster than just using two. You just have to work out where to increase load/grip & where to decrease load/grip ... and how much.

So how do you work a tire more?

The further the suspension travels ... the more load is transferred TO that end or corner of the car,

putting more load & grip on the tire(s) at that end or corner. And more load is transferred FROM

the opposite end or corner, reducing the load & grip on the tire(s) at that end or corner.

Another way we work tires more is simply going faster. Part of that is on the race car's capabilities, which we'll work on improving here. The other part is the driver's capabilities ... and balls. So there's that part of the equation to work into what we're doing.

Here are some basic examples utilizing ONLY SPRINGS as the tuning tool & ASSUMING the

Roll Angle is kept optimum with other tuning tools. Such as sway bars, CG height, roll centers, track width, etc.

As you brake in a straight line the front springs allow load transfer from both rear tires to both

front tires.

• Softer front springs allow the front end to travel more, putting more load/grip on both front tires &

reducing load/grip on both rear tires.

• Stiffer front springs allow the front end to travel less, putting less load/grip on both front tires &

retaining more load/grip on both rear tires.

When you brake & turn at the same time, the outer front spring primarily allows load transfer

from the inside rear tire to the outside front tire.

• Softer front springs allow more travel, putting more load/grip on the outside front tire & reducing

load/grip on the inside rear tire.

• Stiffer front springs allow less travel, putting less load/grip on the outside front tire & retaining

more load/grip on the inside rear tire.

When you are turning, with no braking force, the outside front & rear springs allow weight

transfer from the inside tires to the outside tires.

• Softer front & rear springs allow more travel, putting more load/grip on the outside tires &

reducing load/grip on the inside tires.

• Stiffer front & rear springs allow less travel, putting less load/grip on the outside tires & retaining

more load/grip on the inside tires.

• Softer front & stiffer rear springs put more load/grip on the outside front tire & reducing load/grip

on the inside front tire ... while putting less load/grip on the outside rear tire & retaining more

load/grip on the inside tires.

• Stiffer front & softer rear springs put less load/grip on the outside front tire & retaining more

load/grip on the inside front tire ... while putting more load/grip on the outside rear tire & reducing

load/grip on the inside tires.

In most every situation in life & racing there are "exceptions to the rule" ... this is one of

them. What you read is not a typo. As you accelerate out of the corner, the inside rear spring

WOULD allow load transfer from the outside front corner to the inside rear corner ... IF THE FORCE

was that direction. But it's not. The Force ... when accelerating out of a turn, while still turning ... is to

the outside & rear. So, there is NO FORCE pushing the car onto the left rear ... yet. BUT ... for

optimum acceleration you still need to utilize all the potential grip available with the inside rear tire.

So ...

• Stiffer rear springs keep the inside tire engaged more retaining more load/grip on the inside rear

tire.

• Softer rear springs lessen the inside tire's engagement more reducing load/grip on the inside rear

tire.

As you unwind the steering to straighten the car, but are still accelerating, NOW there is

load transfer to the inside rear tire as the car flattens out.

• Softer rear springs allow the rear to travel more, putting more load/grip on both rear tires &

reducing load/grip on both front tires.

• Stiffer rear springs allow less travel, putting less load/grip on both rear tires & retaining more

load/grip on both front tires.

• There is an exception to this rule, called the "Stiff Rear Spring Strategy" we'll discuss in-depth later.

Did you notice some conflicts? That's what makes this challenging in finding the best compromise

... the best "balance of the grip."

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Let's clarify some things ...

Corner Entry:

1. Softer front springs allow more load & grip on the front tires for better turning ability.

2. Stiffer front springs keep more load & grip on the rear tires allowing the driver to drive into the

corner deeper & brake harder.

3. Too soft of front springs do not allow the driver to go in as deep & brake as hard. Optimizing the

brake bias & shock package helps.

4. Too stiff of front springs makes the car push on entry due to low load & grip on the front tires

5. Rear springs are left out, because their primary role here is working with the rest of the

suspension for optimum Roll Angle.

Mid-Corner:

1. Softer front springs allow more load & grip on the front tires ... allowing for higher cornering speeds

... allowing softer braking on entry.

2. Stiffer front springs keep more load & grip on the rear tires ... requiring lower cornering speeds ...

requiring more braking on entry.

3. Too soft of front springs "would" make the car loose in the middle of the corner due to low load & grip on the rear tires. But typically with too soft of front springs the car will be loose on entry first.

4. Too stiff of front springs makes the car tight or pushy in the middle of the corner due to low load & grip on the front tires.

5. Softer rear springs allow more load & grip on the rear tires for more traction.

6. Stiffer rear springs keep more load & grip on the front tires for better turning ability.

7. Too soft of rear springs can unload the inside front tire & make the car tight or pushy.

8. Too stiff of rear springs can unload the outside rear tire & make the car free or loose.

Corner Exit:

1. Softer rear springs allow more load & grip on the rear tires for more traction.

2. Stiffer rear springs keep more load & grip on the front tires for better turning ability.

3. Too soft of rear springs can make the car push on corner exit due to low load & grip on the front

tires.

4. Too stiff of rear springs can make the car loose on corner exit due to low load & grip on the rear

tires.

5. Front springs are left out, because their primary role here is working with the rest of the

suspension for optimum Roll Angle.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To understand what the suspension is doing, visualize what the race car is doing dynamically:

Forget the car sitting still. Visualize when you come to a corner, you brake first, and the front suspension compresses more or less evenly. A lot of load has transferred from rear to front. The rear tires have less load & less grip. The front tires have more load & more grip.

Now ... you turn into the corner. This doesn't happen "all at once" ... it happens gradually. Let's say it's a right hand corner. When you first move the steering wheel to the right ... load starts to shift to the left side tires.

Visualize the body roll to the outside of the corner. Is your setup for low roll or high roll angle.

The left side front tire is now getting more load than any other tire ... and the loading will increase as you turn the steering wheel more and the car turns harder into this right hand corner.

If you were running a low roll set-up, the inside front tire would still an effective & vital part of the front suspension & grip equation. It's just not doing as much work, or providing as much grip, as the outside front tire, because it is loaded less ... but it is loaded some. If you chose a high roll setup, the inside front tire is not doing much, because it has either no load at all, or very little.

All through the braking zone, the braking force is keeping the front suspension & tires loaded. When you release the brakes ... the shocks' high rate of rebound low speed valving (in the bleed circuit) needs to hold the front end down through 95% of the roll through zone area. The shocks should be just releasing the front end to start coming up at the end of the roll through zone. The timing of this is critical for optimum handling and one of the key areas we tune on in racing. This is covered more in the forum section "Methods & Strategies to Increase Overall Grip."

The front shocks allow the front suspension to extend gradually over the entire corner exit. The rate of this is also critical to corner exit grip. If the front end comes up too quick, the car can push, then snap loose. If it happens too slowly, the grip will be less than optimum.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Let's get clarity on "travel."

Ultimately, for handling purposes, what we care about is wheel travel. The shock is going to travel less. How much depends on the mounted distance & angle. Shock travel is simple to calculate if you know your wheel travel & motion ratio.

As you know, you have to calculate the shock travel (shaft travel).

The formula is:

A/B = C x Cos x WT =ST

A = The dimension from CL of LCA pivot to CL of lower shock mount.

B = The dimension from CL of LCA pivot to center of tire tread. (not the ball joint)

A/B = C

* Do not square it. That is only for spring rate calculations ... not travel.

Cos = The Cosine factor based on shock angle (I use a chart or spread sheet formula)

WT = Wheel Travel at the center of the tread

ST = Shock travel at the shaft

For example:

A = 16"

B = 20"

A/B = C = .75

Cos = For a 22° shock angle is .927

WT = Wheel Travel desired = 4" max in dive & roll

16" ÷ 20" = .80 x .927 = .742 x 4" = 2.967"

ST = Shock travel at the shaft is 2.967"