Recent posts

#41

How to Properly Measure Suspension & Steering Geometry Points / Re: Measuring Suspension & Ste...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 12, 2026, 05:16 PMPart 3 of 3 measuring front suspension points

Time to measure your steering:

10. Inner & outer tie rod ends:

We need the accurate 3 measurements of your inner & outer tie rod ends. This is pretty easy if these are rod ends. If you have OEM type tie rod ends, you need to take them off the car & find the center ... the same way you did the ball joints. OEM style tie rods are basically smaller ball joints with a threaded stud off the said.

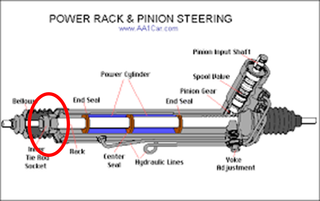

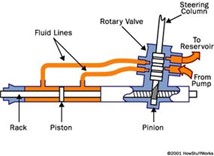

If you have a rack & pinion ... to get an accurate measurement of the inner rack pivot ... you should remove the boots to measure & replace then afterwards.

11. Steering Box, Pitman, Idler & Centerlink pivots:

If you have a steering box instead of a rack & pinion, you'll also need to measure the Steering box, Pitman, Idler & Centerlink pivots. This is trickier than the earlier tasks, because we have to get dimensions that allow the software to calculate the steering pivot axis of the steering box & pitman arm, as well as the idler arm. Be patient & do your best to be accurate.

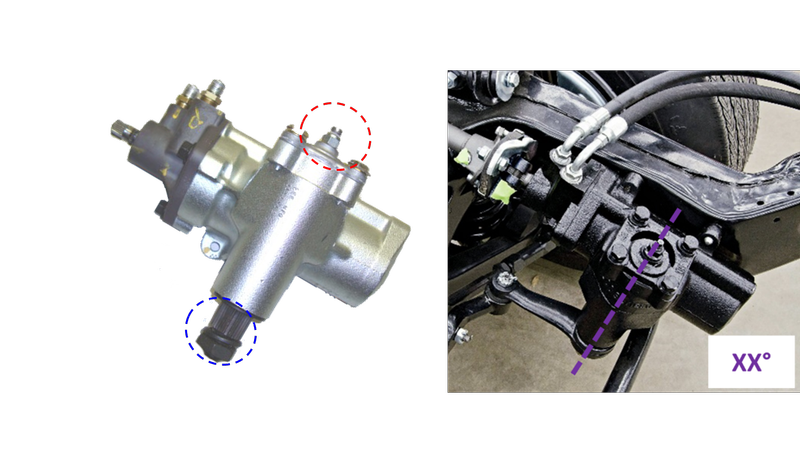

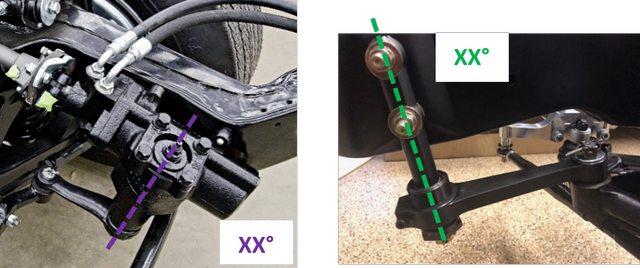

On the steering box, we need to gather the 3 dimensions on the stud sticking out of the top of the box (See red dotted circle in photo below on left) & the 3 dimensions on the splined shaft sticking out of the bottom of the steering box (See blue dotted circle in photo below on left) that the pitman arm attaches to. Ultimately, this is to calculate the steering axis as shown by the purple dotted line in the photo below on the right. To help find the center, there should be divots in each end.

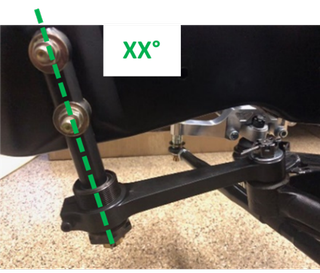

We need to do the same for the idler arm. This is harder if the idler shaft is stepped, like many factory units (on left in photo below). If the shaft is straight, like this Howe Racing unit (on right in photo below), it's easy. With the OEM unit, I ignore the step. Since I plan to mount it level on the side of the frame, I make my "Out from Chassis Centerline to Idler Pivot Axis" the same at top & bottom. Because that is how it will work.

Now to get the correct steering axis, we still need to measure top & bottom from front axle centerline and from the ground, to arrive at the Idler Arm's rotational axis. (See Green dotted line in Photo below)

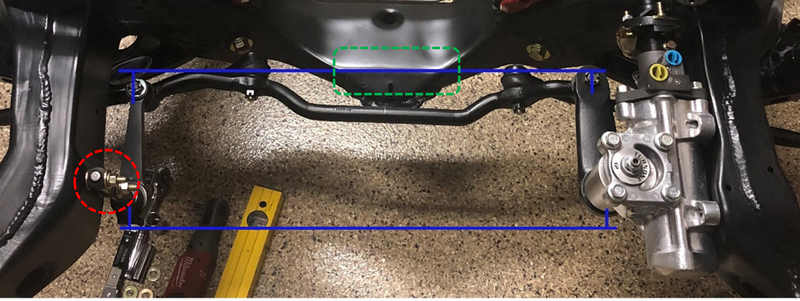

Lastly, with your steering linkage still assembled (See photo below) we want to measure the 3 dimensions of the centerlink pivot points, where they connect to the idler arm & pitman arm. Remember we need the pivot points. There are several designs of centerlinks. Some have the pivots in the actual centerlink. Some have the pivots in the ends of the idler & pitman where they bolt to the centerlink. Regardless of shape of style, you need the 3 measurements to each of the centerlink's 2 pivot points.

#42

How to Properly Measure Suspension & Steering Geometry Points / Re: Measuring Suspension & Ste...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 12, 2026, 05:14 PMPart 2 of 3 to measure suspension points

3 types of measurements:

1. Height ... from the ground up to the pivot point

2. Outward ... Left or right ... always from the car centerline to the pivot point

3. Fore or Aft ... from the axle centerline to the pivot point

We sometime refer to these as X, Y & Z measurements

What you're measuring ... in order:

1. Car ride height front & rear

2. Car centerline

3. Axle centerlines front & rear

4. Track Widths front & rear

Front:

5. All four ball joints ... at true center of their pivot

6. All 8 control arm pivot centers (2 for each upper & lower control arm)

7. Shock pivot centers (upper & lower)

8. Spring end centers (upper & lower) if not coil-over

9. Sway bar attachment points to A-arms

Steering:

10. Inner & outer tie rod ends

11. Steering Box, Pitman, Idler & Centerlink pivots if steering box

Rear: (IRS – Same as front)

Rear if straight axle:

12. All rear linkage pivot centers (2 for each link)

13. Panhard bar or Watts if utilized

14. Shock pivot centers (upper & lower)

15. Spring end centers (upper & lower) if not coil-over

16. Sway bar attachment points to & axle or chassis

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Here is detail for each area of measurements:

1. Car ride height:

Pick a spot on the bottom of the frame rails that will be easy to measure now & in the future. The further apart you go, the more accurate. Most Racers usually pick a spot in front of the rear tires & a spot behind the front tires ... if the frame rails are wide at that point & out near the rocker panel. Either pick a spot with identifying holes or marks on the bottom side of the frame rails ... or make something to

permanently mark these spots. You'll use these for the life of the car, no matter what changes you make.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

2. Car centerline & front axle centerline:

Before we start, "mark down" means using either the laser or plumb bob & string ... along with painter's tape & a sharpie ... to put a mark on the floor exactly where a point is. Some people use the term "transfer" ... meaning to transfer a point on the chassis or suspension onto the ground. I don't like marking on my epoxy coated floors, so I put blue masking tape down first & write on it with the Sharpie marker.

This measuring process is difficult & somewhat subjective. Pick a section of the frame that looks symmetrical ... and either go inside or outside (but use the same on both sides of the car) & "mark down" ... putting a dot or "x" on the floor. Do this in 3 spots, using 3 different sections of the front frame. Then, do this in the rear, using 3 sections of the rear frame. Now find the center of those 6 frame sections, using tape & sharpie again.

Next, with a friend's help, pull your chalk line taut ... down the center of the car ... on the floor ... and the string "should" hit all 6 frame section centers. If it doesn't, either recheck your measurements and/or re-evaluate your choice of locations. Ultimately, you're going to put a chalk line on the floor using the marks you trust. That is the car centerline that everything is going to be measured from & to.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

3. Axle Centerlines:

Start in the front. A simple way to do this is to pull a taut string behind the front tires, on the floor, and mark the string location on both sides. Do the same in the front. Split the difference & that is the front axle centerline. Problems only occur with this method with different tires, different pressures, suspension or tire bind from not rolling it into place straight.

Put a chalk line on the floor representing the front axle centerline. Many things, but not all, will need to be measured from & to this point. For all things in front of the front axle centerline, express them in negative or minus numbers. Example: if something is 2 & 3/8" in front of the front spindle centerline, write it down as -2 & 3/8". Everything behind the front axle, express as positive numbers.

Do the same for the rear axle. The only difference is everything behind the rear axle, express as negative numbers.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

4. Track widths front & rear:

Just for clarification ... "tread width" is outside to outside of the tread. "Track width" is center to center of the tires. A lot of people get those confused & our conversations get sidelined.

We need to know the track width ... the true center to center of the front tire contact patches. Several options, but here is a quickie. Start in the front. On the front side of the tires ... measure from the outside of the tread width on one tire ... across to the inside tread width on the other side. Do the same on the back side of the front tires ... and average the two numbers ... to account for any toe in or out. If you get 55-1/2 at the front of the tires & 55-3/8" at the rear of the tires, average that to 55-7/16".

Do the same in the rear. BUT ... if you have any "toe" in the rear, and your rear suspension is not IRS, you may want to address this.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

5. Locate all four ball joints ... at true center of their pivot:

Since you have already pre-measured ball joints, this part is not as tough as it is if you're trying to find the pivot centers while measuring. Eyeballing these pivot centers ALWAYS leads to inaccurate data. Use your measurements from the top off the housing, or the end of the stud, to the axle centerline & work out the math. Double check by eyeballing to see if your math places the pivot center where it actually is.

Your Roll Center locations & Camber Gain numbers will only be as accurate as your measurements. This is a time consuming & somewhat tedious operation. I always suggest people take the time to do it right the first time, so you don't have to do it over (or suffer handling problems from incorrect tuning).

You need to measure the location of each ball joint in 3 directions ... all based on the true pivot point of that ball joint. You need the ...

1. Height ... from the ground up to the pivot point

2. Left or right ... always from the car centerline

3. Forward or backwards ... of the front axle spindle centerline.

Reminder: for all things in front of the front axle centerline, express them in negative or minus numbers. Example: if something is 2 & 3/8" in front of the front spindle centerline, write it down as -2 & 3/8". Everything behind the front axle, express as positive numbers.

I can't stress this enough. Make sure your tape is both straight & a true 90 degrees to what you're measuring. Having the tape measure angled any direction other than a true 90 degrees will produce incorrect numbers. This is hard to see when you're holding the tape under the car in a tight spot.

Use your friend as a "spotter" to insure your tape is straight up & down for height measurements on 2 planes ... and 90 degrees to the car centerline & level for right & left distance measurements.

There are times when it is more accurate to ...

• Use a tape and measure directly.

• Hang a plumb bob on a string off the point, or near it, and measure.

• Utilize the laser (and level) to point up or down & transfer the measurements.

• Use the level to extend a point out to where you can use the tape measure.

• You'll just have to use your best judgment or try it different ways.

I like to mark on tape on the floor ... so I don't forget (I'm old). I put "points" on the tape along with the measurement ... so I can find the point again easily to re-measure if I want or need to ... and so I can re-check my measurements. I check my numbers & recheck them several times. So when I capture them all ... I KNOW THEY'RE RIGHT ... and can trust the data & results.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

6. All 8 A-arm pivot centers (2 for each upper & lower control arm):

You need to measure the location of all 8 A-arm pivots in 3 directions ... all based on the true pivot point of the bushing. You need the ...

1. Height ... from the ground up to the pivot point

2. Left or right ... always from the car centerline

3. Forward or backwards ... of the front axle centerline.

(See image above) For the upper control arms ... you can simply measure off the ends of the pivot shaft. For the lower A-arms, I need you to measure each bushing bolt ... on both sides ... and average the numbers.

For example: If the center of the bolt at front of the driver side lower A-arm is 8-11/16" in the front of the bushing & 8-9/16" in the back of the bushing ... you will average that to 8-5/8". That is the height of that bushing.

When measuring from the car centerline, the differences are bigger, because the lower control arm may be angled (top view). So, from car centerline, if the center of the bolt in front of the bushing is 10-1/16" & the center of the bolt on in the back of the same bushing is 10-7/16" ... you will average that to 10-1/4". That is the distance from the car centerline to the centerline of that bushing.

If this same bushing is 1-1/2" ahead of the axle centerline on one side & 1-7/8" ahead of the axle centerline on the other side ... you will average that to 1-11/16" ... and because it is AHEAD of the front axle centerline, you need to express it as a negative, so write it as - 1-11/16"

We need all 3 dimensions on all 4 bushings.

7. Shock pivot centers:

The process should be getting simpler by now. You're measuring to find the front shock pivot point centers. We need all 3 dimensions on the top & bottom of the shock bushings or bearings.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

8. Coil spring end centers:

If you have coil-overs, skip this step, as the spring does whatever the shock does. If you have separate shocks & coil springs, carry on this step. A little tricky to measure ... but we need measurements from the center of the spring top ... to the front axle centerline & car centerline ... and the height. We need the same thing for the bottom of the spring ... for both front springs.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

9. Sway bar attachment points to front control arms:

We need the 3 accurate measurements from the center of the sway bar link ends, where they connect to the lower control arm.

If your sway bar has linkages that mount off the side of the sway bar arm ... you want to measure to the center of the connection points on the A-arm ... NOT the center of the sway bar arm. Sway bar arm length matters to calculate your actual sway bar rate. So now is a good time to measure & record it. Measure from center of main sway bar to center of pivot on sway bar arm ... 90 degrees from the main sway bar ... regardless of angle or shape of the arm.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

#43

How to Properly Measure Suspension & Steering Geometry Points / Re: Measuring Suspension & Ste...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 12, 2026, 04:59 PMLet discuss HOW to map out your front suspension geometry points

This may sound funny, but I do not know what spring & sway bar rates a car needs without running calculations based on the car's geometry. Frankly, I don't know the optimum camber, caster, roll centers & so on ... until I know the car's entire geometry picture. I offer two "Tech Services" ... Tech #24 & Tech #40... to assist Clients dial in and/or Improve their race car's performance.

Tech Service #40 entails:

* I send the client a link to these measuring instructions & 3 measurement forms

* They measure their car's suspension & steering points accurately & return the completed forms

* I plug all the info into my software & see what each area of their geometry looks like

* I evaluate each area that affects performance & gather the information for a client discussion

* We discuss what's wrong with their race car's geometry & how that affects our possible strategies

* We discuss front end suspension travel & car roll angle strategies & the client decides on the best one for them & their racing goals

* I share with them what to do & how to do the changes to improve the geometry & track performance

* The client makes the physical changes on their car - Some involve minor fabrication & welding

* If it is a production car from the 1960's to 1980's we can plan on truing up the lower control arm pivots. More on this later.

I then work out a "set up" which includes:

* Front spring rates based on the travel strategy chosen

* Front sway bar rate based on the roll angle strategy chosen for different courses

* Rear spring rates based on the roll angle strategy chosen

* Rear sway bar rates to achieve handling balance with holes for fine tuning

* Rear roll center height (IRS, Panhard Bar or Watt's link) for handling balance & grip

* Static Camber & Caster Settings for optimum tire contact patch dynamically when the car is in dive & roll

* Toe & Ackerman settings for optimum turn in, tire slip angle & inside front tire grip

Tech Service #24: Is just for new setups. It requires I already have the geometry in my software, from either doing a Tech #40 before ... or if I designed the race car's geometry.

You can see more details on both Tech #24 & tech #40 HERE

If you are doing your own geometry optimization, you'll need to purchase a software. I used to keep up on the brands & versions available, but not anymore. So, I don't have any recommendations these days, other than Performance Trends. I've used several brands & versions & I always go back to Performance Trends Suspension Analyzer. It's simply to use, accurate & affordable. What else are you looking for?

None of them will tell you the results are good or bad. Everything is just numbers. You'll have to know what numbers you're shooting for. I share some of that in the other forum threads, like what kind of anti-dive percentage I target, FLLD percentages, etc. Being perfectly frank & transparent, I'll share you with a lot of what you looking for, but not all. Intentionally. Hey! A girl has to keep some of her secrets.

Part 1 of 3 - Preview:

Whether you're measuring your race car for you or me to enter into a suspension geometry software, it is critical you take your time, double measure & gather accurate dimensions.

You're going to measure all of the pivot points in your front suspension, steering & rear suspension, plus front & rear track widths, sway bars, shock & spring points. You need what engineers call the X,Y,Z dimensions. In other words, you need the dimension to each pivot point.

• OUT from CHASSIS CENTERLINE

• UP from the GROUND/FLOOR

• FORE/AFT of the respective AXLE CENTERLINE

• I'll just refer to these as getting all three dimensions.

Once you, or I, input the dimensions into the suspension software & we'll get clear on your CURRENT:

• A-arm Instant Centers

• Static Roll Center locations

• Dynamic Roll Center location*

• Scrub radius

• Camber Gain

• Dynamic Camber in dive & roll*

• Spring Motion Ratios

• Actual spring rate at the wheel aka Wheel Rate

• Sway Bar Motion Ratios

• True rate of your Sway Bars

• Shock Motion Ratios

• Shock Valving rate at the wheel**

• Anti-Dive

• Ackerman

• Anti-Squat

• And more.

From there, we'll be able to make informed decisions on A-arms, ball joints, spindles, etc ... to achieve optimum front geometry for your goals. So, we can dial in the whole list above to the optimum settings (within physical & financial possibilities). Plus adjustments to the rear suspension to optimize it as well, and balance the handling.

I will show you how the information can guide us on part & tuning decisions, after we lay it out, along with what all the info means. If there are Engineers following this post, you're going to dislike some of my terms. I apologize in advance. Sometimes I use the engineering term. Other times I use what I call as "car guy" terms.

In this post, I'll lay out a method to measure all of the pivot points in your upper & lower A-arms, steering, rear suspension links, plus track width, sway bar, shock & spring points. There are hundreds of ways to doing most things. I'm laying out one way I think most Racers can do in their garage. You will need some basic tools & creative body language when it comes to getting into difficult spots. This method will take a little longer, but we will have accurate numbers ... AND ... as you make changes, you will need to take only a few measurements & we'll still know where everything is.

These dimensions are important, so taking your time, measuring several times & even measuring different ways will ensure we have accurate numbers.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Tools:

You will need a good tape measure. Use just one ... so if the end isn't dead zero perfectly accurate, at least all the measurements are the same. Every 1/16" matters.

Tool check list or shopping list:

• Good, readable tape measure.

• 4-6" dial caliper or digital caliper.

• Short laser level (6-10")

• Framing squares in sizes that fit under your car

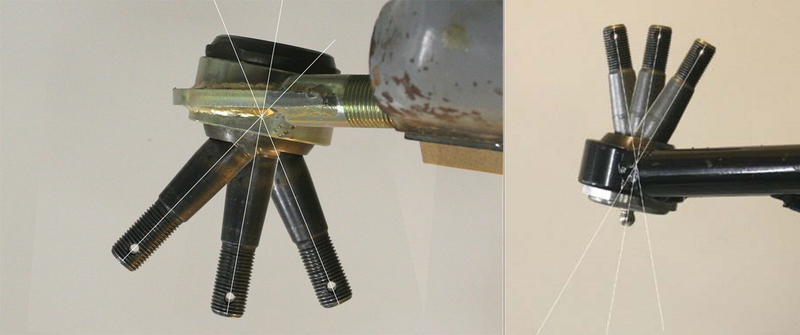

• 2 Bob weights (See image below)

• Chalk line (blue will come off your floor eventually. Red is not coming out ... ever)

• Roll of quality string

• Removable masking tape (Blue 3M works best)

• Sharpie fine point marker(s)

• Brake Cleaner & paper towels

• Note pad & pens

Home Depot or Lowes has everything in one stop if you need something.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

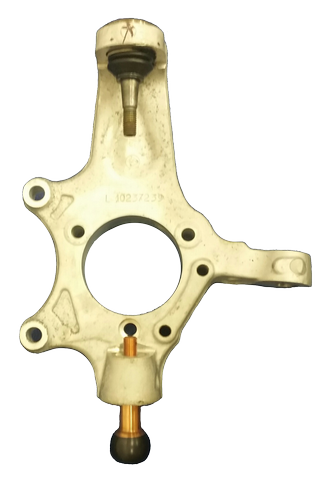

Pre-measure Ball Joints:

If you have some spare upper & lower joints ... great. If not, make a stop at your local, friendly auto parts store where you buy parts. You'll need to borrow an upper & lower ball joint to measure at the counter.

Guys, don't use a "generic" ball joint. Use the part numbers for your car.

(See image above). Take a ball joint & lean it all the way to the right & draw a Sharpie line on the housing ... in line with the BJ pin. Now lean it left & do it again. Now straight up & do it. There is your true pivot center. Take your dial/digital calipers & measure from the pivot center to the top of the housing & again from the pivot center to the end of the stud.

Do both upper & lower ball joints & write down all the numbers. When you're under the car, getting to the top off the housing or the end of the stud will be WAY easier to achieve. You just need to do the math ... along with measuring ... to arrive at the true pivot center locations on your car.

What was the brake cleaner & paper towel for? To clean off your Sharpie marks on the ball joint housings. Plus clean stuff under your race car as you go.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Before you start:

a. Plan for this to take at least a full day or more.

b. You'll need a helper to hold the other end of the tape and to "spot" for you.

c. Work out how you're going to put the driver weight in the seat. Don't use a person. (We use lead)

d. Put your track tires on & set the tire pressures just like you compete with.

e. Get the car as close to "race ready" as possible: fuel level, stuff out of (or in) the car, etc.

f. CRITICAL: Document all numbers & details on paper, so we can refer back later.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

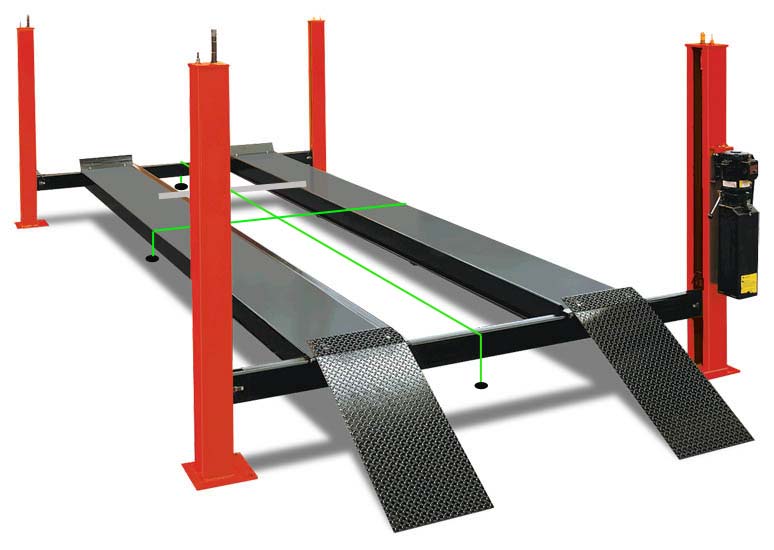

Platform:

The tires & suspension have to be "loaded" just like the car is on the ground. So, you can't use a chassis lift or jack stands. You can use a drive on lift & I strongly urge you to find one to use if you can, because it is the easiest. Drive on Lifts have two advantages. One is you can adjust the height of the car to work under. The second is you utilize strings with weights on each end (like the image below) to create your "ground line" to measure from. This is pretty accurate. You just slide the strings where you need them to measure each time. I've also seen guys with shop access use muffler & oil change pits, where they can walk under the car.

There are 2 other good ways. Just remember the car has to be on its tires, just like ride height, but you need to be able to get under it. On Stock Cars & NASCAR Modifieds we use 10" Joe's Racing stands & simply add 10" to all of our height numbers. You "may" be able to do this on the garage floor, but it is harder. Depending on ride height your fat ass may not be able to get under the car well, or at all.

If you're measuring from the floor, pick a spot in your shop as flat as possible with minimal dips. With a friend, pull strings taut over the area & look for low & high spots. Avoid areas with high spots. Low spots are OK, because you can account for them. How? Simply put painter's tape on the low spots with the dimension of how low the dip is, below the taut string (3rd person?). Then you can subtract that dimension from your measurements when in that area.

For example, if the dip is 3/16" and you measure from a pivot point to that dip & get 15-5/16" ... subtract the 3/16" ... and your true dimension is 15-1/8". Make sense? Don't add the dip number. Subtract.

I've seen guys use under tire, car ramps & custom built stands ... shimmed so all 4 are the EXACT same height. So, give this some thought on where & how works best for you. If you rig something up to raise the car, all 4 stands need to be the EXACT same height. Any height will do, but they have to be the same. Whatever the number is, you will be subtracting it from your height numbers to get true numbers, as if the car was on the ground.

Another option if you're using stands, is to level them to each other & run strings or straight edges across the tops of the stands, similar to using a drive on ramp lift.

Do NOT use a jack or jack stand under the lower control arm or ball joint. It is not accurate, because it loads the suspension at a different point. Do not use jacks under the ball joints like shown in the pictures above. No matter how careful you are setting the spindle pin in the correct height, this method will end up causing inaccurate measurements. Put tires on the car and get your measurements with the front suspension under weight and the suspension relaxed, not in bind. Most of you will be able to do this with the tires & wheels on. Do it that way if you can.

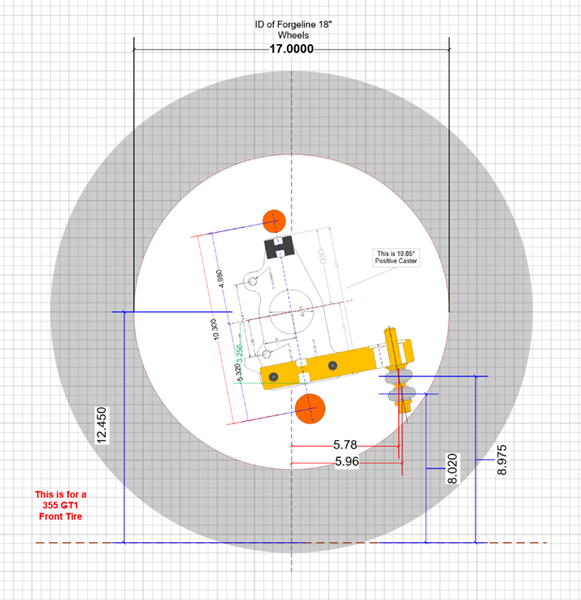

If you have deep back spaced wheels (like our road race cars) & the ball joints are deep inside the wheel & make this too difficult to measure accurately ... and the wheels have to come off ... use adjustable wheel stands like the photo below. Adjust them until the center of the hub is EXACTLY the same height as is was with the tire & wheel on, all four corners. Frankly this is how we do all of ours, but there is an expense to buy them. We also use them on top of perfectly level scale plates in our race shops, so we don't have to account for uneven floor surfaces. But you gotta use what you have access to.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Pull the car into your "space" straight. Make sure the front wheels are "dead true straight" as you roll it in & do NOT turn the steering wheel once you're in your spot. Back up & do it again if you need to.

A simple way to check & confirm the front wheels are "dead true straight" ... is to pull a long, taut string across rear tire & front tire on one side ... at the same height (preferably axle centerline) ... and pay attention to how it lays across the front tire. Do both sides.

If the car is toed-in, the gap between the string & front sidewall, of the front tires, should be the same on both sides. If the car is toed-out, the gap between the string & rear sidewall, of the front tires, should be the same on both sides. If a gap is bigger on one side, the steering is not straight. You don't want to have to turn the wheels ... in their spot ... and leave them, as there will be "tire bind" (unless you have grease plates under one or both tires so they freely slide). Get it true & back the car up 2' & roll it into place again if you need to.

#44

How to Properly Measure Suspension & Steering Geometry Points / Re: Measuring Suspension & Ste...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 11, 2026, 03:54 PMFirst, Let's Talk About What We're Measuring & Why

We cannot go any faster through corners than the front end has grip & the front roll center is the #1 priority to front end grip.

Front Roll Centers:

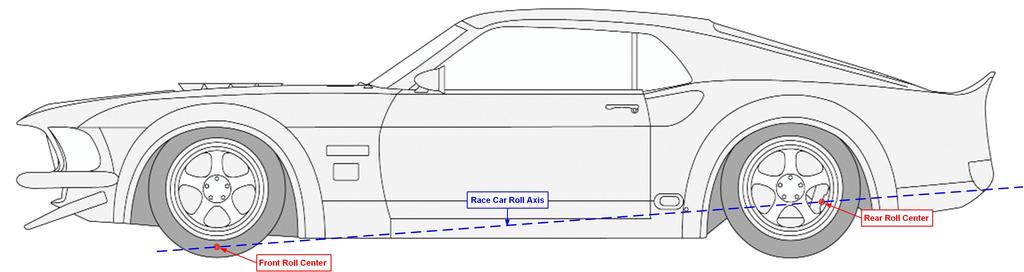

I'll be very basic for any readers following along that are completely new to this & apologize in advance for boring the veterans with more knowledge of this. Cars have two roll centers ... one as part of the front suspension & one as part of the rear suspension. I'll first explain what role they play in the handling of a car ... and then how to calculate the front roll center.

Think of the front & rear roll centers as pivot points. When the car experiences body roll during cornering ... everything above that pivot point rotates towards the outside of the corner ... and everything below the pivot point rotates the opposite direction, towards the inside of the corner. Because the front & rear roll centers are often at different heights, the car rolls on different pivot points front & rear ... "typically" higher in the rear & lower in the front.

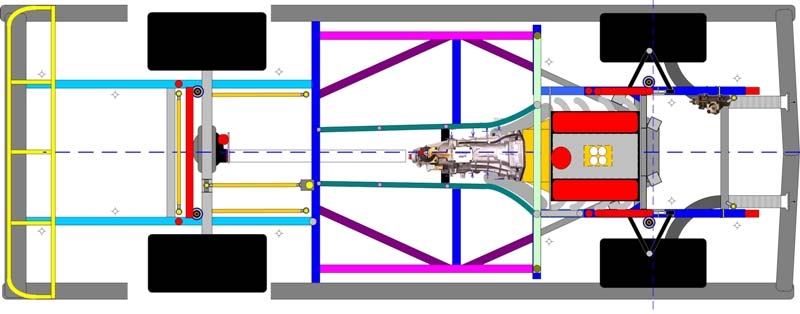

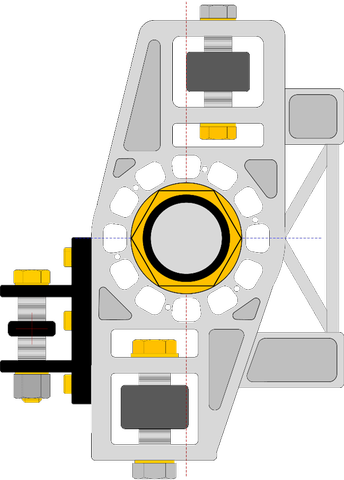

(See image above) If you were to draw a line parallel down the middle of the car connecting the two roll centers ... this is called the roll axis ... that line would represent the pivot angle the car rolls on ... again "typically" higher in the rear & lower in the front. (See image below) If you had a bird's eye view from the top, the roll centers should be in the center of the race car.

The forces that act on the car to make it roll ... when a car is cornering ... ... act upon the car's Center of Gravity (CG). With the race cars we're focused on, the CG is above the Roll Center ... acting like a lever. The distance between the height of the CG & the height of each Roll Center is called the "Moment Arm." Think of it as a lever. The farther apart the CG & Roll Center are ... the more leverage the CG has over the Roll Center to load the tires & make the car roll. While more grip is the goal, excessive chassis Roll Angle is your enemy, because it over works the outside tires & under utilizes the inside tires.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Locating Your Front Roll Center:

Measuring all the pivot points in the front suspension to calculate the Roll Center in the front suspension of a double A-arm suspension car can be tedious ... but the concept is quite simple.

Your UCA & LCA have pivot points on the chassis ... and they pivot on the spindle at the center of the ball joints. Forget the shape of the control arms ... the pivots are all that matter.

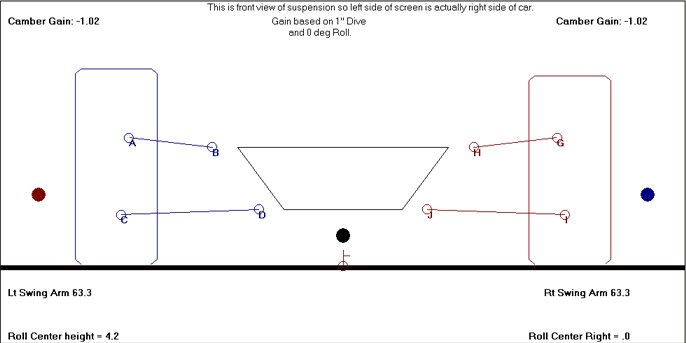

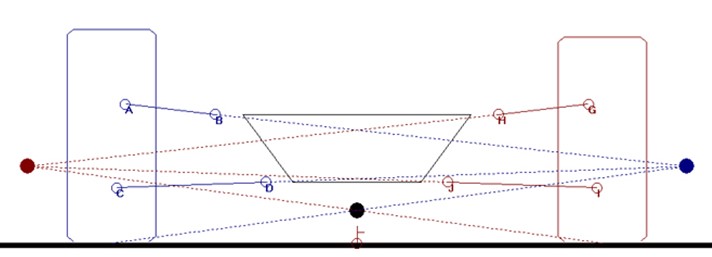

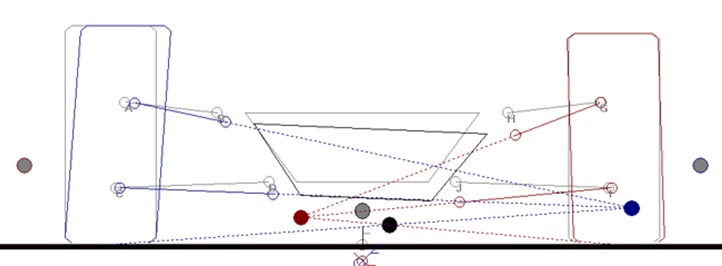

If you draw a line through the Centerline of the Upper Control Arm pivots & another line though the Centerline of the Lower Control Arm pivots ... they will intersect at some point (as long as they are not parallel). The point of intersection is called the instant Center (IC). Look at the drawing below. The red colored dot on the left represents the Instant Center for the red control arms on the right. Blue is the other side. These are accurate for the static car at ride height.

The UCA/Spindle/LCA assembly travels in an arc from that IC point. However far out that IC is ... measured in inches ... is called the Swing Arm length. Longer swing arm lengths produce less geometry change through travel. Shorter swing arm lengths produce more geometry change through travel.

Still using the image above, next you draw a line from the Centerline of the tire contact patch at ground level ... to the Instant Center of the control arms on the opposite side. Do this on both sides.

Look at the image above again & notice the black dot. Where the two "tire contact patch lines to Instant Center Lines" cross (intersect) ... where the black dot is ... is the static front Roll Center at ride height. The black dot represents the Static RC at ride height.

In the image below, we compressed the front suspension 1" & rolled the car 1°. This is a dynamic condition under braking & turning. The red & blue Swing Arm Instant Center dots moved. Unevenly ... due to body roll. The roll center moved down (due to dive) & to the right (due to body roll). We call this roll center migration. We care about this MORE than the static roll center location. But we have to measure the car statically ... obviously. Then we plug the dimensions into chassis software & work out real world dynamic situations.

Make sense?

#45

Front Suspension & Steering Geometry for Track & Racing / Re: Front Suspension & Steerin...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 10, 2026, 02:31 PMNOW... How to Square & Equalize Your Steering Linkage

What we care about, and therefore what needs to be fixed & optimized in our steering, is:

• Squaring the steering linkage, so the car steers the exact same both ways (they usually don't).

• Truing & equalizing the steering linkage dimensions & angles so it doesn't drop or arc differently.

• Eliminating any bind or stiction in the steering that telegraphs incorrect signals to the driver.

• Getting the Ackerman optimized, to increase the inside tire slip angle to increase front end grip.

• Utilizing the increased Ackerman to increase caster on the inside front tire for a full contact patch.

• Eliminate any slop, or delay, in the steering, so the car responds quicker at corner turn in.

• Relocating the inner tie rod pivot points to achieve the cleanest, smoothest bump steer arc.

• Performing the bump steer operation to achieve our bump steering goals.

Ok. Before we get rolling here on the "How-To" square & equalize your steering system, you need to know this is quite involved. All winning race teams don't give it a second thought. But realize you're looking at 2-3 days of patience trying work if you're new to this. If you're not up for it, then reconsider buying a complete clip or chassis for your car. But if you are "committed" to making your car handle, steer & perform at high levels on track, autocross, etc ... here are the instructions, in order:

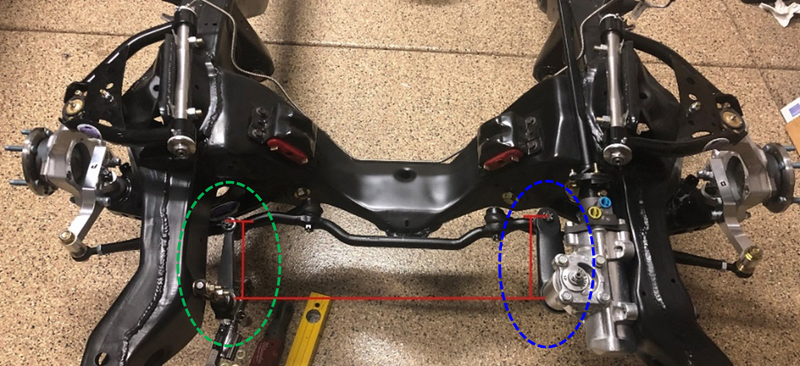

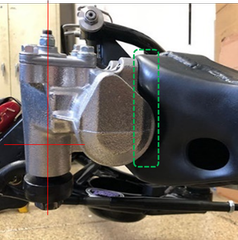

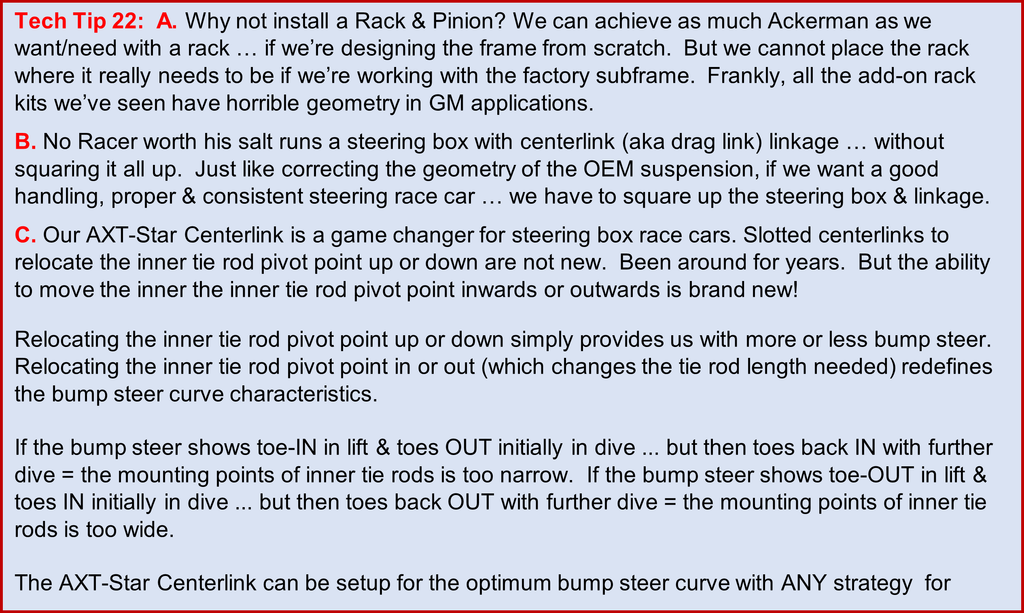

Step 1. You need to "True-Up" your steering box. The box isn't the problem. It's the old, stamped, formed & welded OEM frame rails. You want to use shims & machined washers (no stamped washers) in-between the frame & steering box (Green Dotted line in Image Below) on the 3 or 4 bolts attaching it to the frame ... to get the box BOTH level with the earth & parallel to the chassis centerline. Use as few shims/washers as possible, so not to push the steering box inward toward the chassis centerline, anymore than necessary to get the box level with the earth & parallel to the chassis centerline.

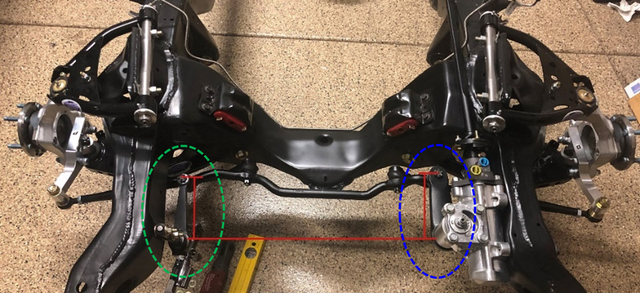

Step 2. (See Image Below) You will want to get a pitman arm (the arm that goes on the splines of the steering box – blue dotted oval) and the idler arm (the arm that bolts to the passenger side frame rail – Green dotted oval) to have the same length arms.

Sometimes they come that way from the factory ... often not. It's not uncommon to see the idler arm and inch or so shorter or longer than the pitman arm.

Look again at the photo image below to see the relation of the idler arm to the pitman arm.

• If the length of these two arms is different ... you have issues.

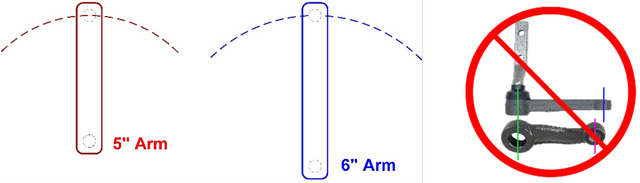

See example of a 5" & 6" arc in the illustration below on the left side. The arc is very different, but those arms are only 1" different length. If the idler arm & pitman arm are different lengths, the ends of centerlink will be on those different arcs. It can not stay a true 90° to the chassis. Your car will ... if it doesn't already ... steer differently & handle differently on left & right corners.

Look again at the photo below:

• If the pivot axis of the steering box (purple dotted line in the image below) differs from the pivot axis of your idler arm ... your centerlink won't stay a true 90° to the chassis ... and you have issues.

• You want to measure the steering box pivot axis in degrees (Image below) & mount (or remount) your idler arm shaft to the same angle to have true & square steering.

OK. Let's fix it! Measure your pitman arm & save that number. When you look at various length pitman arms, realize that shorter arms slow the steering & longer arms quicken the steering. When you get a new pitman & idler, they need to match in length. It would be helpful to use an idler arm that is adjustable for height to make getting the centerlink level & bind-free an easier chore. The Howe Idler (shown below) has the arm on a threaded adjuster. It is quick & easy to adjust the height & get the centerlink level & bind free. We also use a idler arm from Wenteq racing (not shown) that uses spacers & shims to adjust the height.

If you purchase our steering box & linkage package, called the AXT-STAR Steering System, it comes with all the correct components to create amazing steering. You have work to do to square up your steering. The kit just gives you the right parts to do the job. The Howe or Wenteq Roller Bearing Idler Arm & Howe or ProForged Pitman Arm that's included in your package are the same length. Both the Howe or Wenteq Roller Bearing Idler Arm are adjustable for height to make getting the centerlink level & bind-free easier.

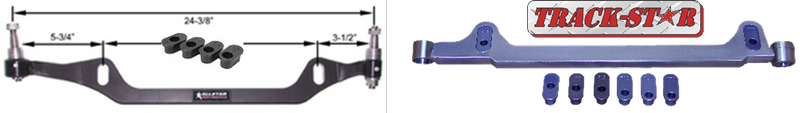

Step 3. Decide on centerlink. You have options that vary in cost. Ideally, budget permitting, you'll use a "slotted & slugged" centerlink that allows you to adjust the height of the inner tie rod pivot. The images below show one from Allstar & the other is our Track-Star versions with bearings on each end. What most folks don't think about ... is when they lowered their car significantly ... the steering linkage & inner tie rod pivots lowered as well. But your outer tie rod did not.

To get your bump steer curve smooth again we can't just lower the outer tie rod point alone. We're below the proper axis & need to raise up the inner tie rod pivot point. With the Allstar & RSRT Track-Star racing centerlinks, the spacers & shims on the outer posts can adjust the centerlink height lower or higher from the pitman & idler. Then with precision offset slugs, we can place the inner tie rod end at the optimum height.

The Allstar offset slugs are 1/8", 1/4" & 3/8", giving us a range of 3/4" in 1/8" increments. If that range works, we can fine tune height smaller than 1/8" with shims in the outer pivot posts. The RSRT Track-Star offset slugs are offer a range of 1.50" in 1/16" increments. If we need to get tighter than that, we can fine tune height with .005" & .010" shims in the outer pivot posts.

With the Allstar & RSRT Track-Star billet steel centerlinks, we also move the inner tie rod pivot point outward as this shortens the overall tie rod length. This helps the bump steer curve even more on lowered cars. Another difference in these two are the Allstar utilizes greasable stell bushings on the outer pivot posts, while the Track-Star utilizes bearings.

The AXT-STAR centerlink above is almost a magic wand for our steering goals. In addition to adjustable height outer posts, bearing ends & a slug range of 1.50" in 1/16" increments ... it allows you to relocate the inner tie rod pivots inward or outward with clamp on inner tie rod posts. This is made with 4140 chromoly & each posts clamp on with 6 bolts & 3 set screws.

With all of these aftermarket racing centerlinks ... and utilizing rod ends instead of OEM tapered bolt tie rods ... we can adjust the Ackerman. We can reduce Ackerman by mounting the rod end as close to the centerlink as possible with no spacers. And we can increase Ackerman by using longer bolts, spacers & shims to push the rod ends further rearward, toward the FACL. This is what we used to do when we raced cars with steering boxes.

Step 4. If you trued up your steering box to the frame, when you attach the pitman arm, that side of the centerlink will be level if you take the droop out of it. What I mean is, if you bolt the centerlink to your pitman arm & just let it hang, the weight of the centerlink will droop on the end where the idler arm would go & bind up the bearings on the pitman arm end. You'll want to find the "center" of the two bind angles.

Do this ... put a digital angle finder on the centerlink & let it droop. For conversation sake, if it said -1.3° ... and you put your hand under the free end (idler arm end) and lift until you feel bind the other direction ... and your digital angle finder reads +1.3° ... you'll know that level (0.0°) will be zero bind. That is where you want the centerlink to be ... level. (If you get significantly different numbers, for example your angle finder reads -2.0° in droop & +1.0° in lift, your steering box may not be level.)

OK ... attach the idler arm to the open end. Use an adjustable jack stand, shims, old KC & the Sunshine band albums ... whatever you have ... to hold the centerlink level. Your next step is make it a true 90° to the chassis centerline. There are a lot of ways to achieve this. If you already trued up your suspension, then your FACL (Front Axle Center Line) lines on the floor are the BEST way to check this.

Step 5. With the centerlink level & truly square to the chassis, and the idler arm attached to the centerlink, swing the idler arm up to the side of the frame. Do the bolt holes line up? 9 out of 10 times = No. Don't sweat it. This is part of the process. You may need to modify the holes or weld them up & redrill new holes, depending on how far they're off. Before you do that, let's get the Idler arm EXACTLY where it goes.

Here are the factors that determine where to mount the idler arm (See image below):

• With your centerlink level & parallel to your FACL.

• Whatever the angle of the steering box axis is (see purple dotted line in photo on the left) ... the idler arm "post" pivot axis (green dotted line in the photo on the right) needs to be the same.

Next, measure from center-to-center of your centerlink pivots. For example only, let's say yours is 24-3/8" (see blue line example below). Then you need the pivot center of your idler arm to be the same dimension from the center of the splined shaft your pitman arm is attached to.

As long as you are not using an OEM idler arm (or copy) & you're using a height adjustable racing style idler arm with a mounting "post" (Red dotted circle in image above) it should need to be spaced away from the frame some amount. Figure out that amount to get your idler arm post in it's correct location. If the gap is small enough, use a few aircraft machined washers & shims (like in our kit). If you need spacers too, we have another kit with spacers & shims. The bottom line is you want the "idler arm post to splined steering shaft" to be the same dimension as the centerlink pivots.

Lastly, you may need to cut off the "nose" (see green dotted rectangle in image above) on your crossmember & box it with a plate, for clearance.

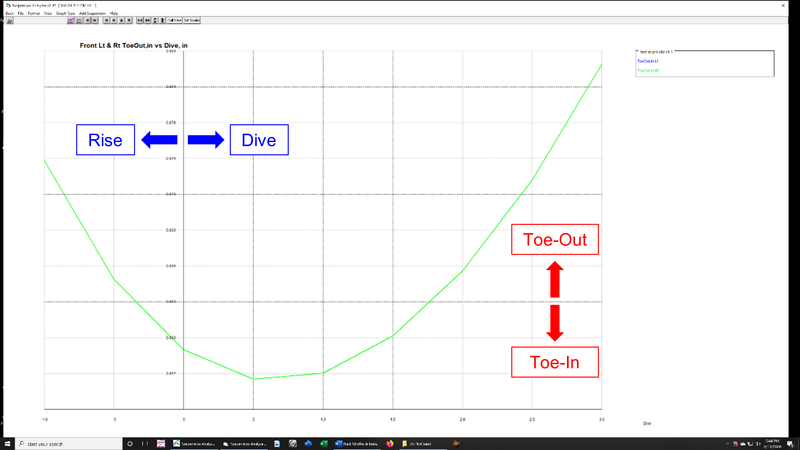

Step 6. Bump Steer is used as a noun & a verb in racing. When you are measuring & adjusting your car's bump steer ... we call it "bump steering your car." When it's done we care what the actual bump steer graph looks like ... how much bump steer you have throughout your usable travel ... and which way it goes. We call gaining toe out in dive (suspension compression) as "bump out" and we call losing toe-out in dive "bump in" regardless if we're actually toed in or out statically.

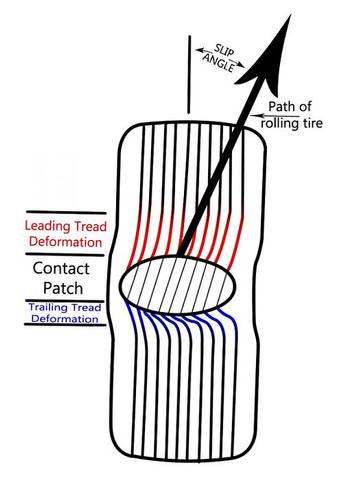

Let's get some basics out of the way. This is not your Grandma's daily driver. This is your race car or at least the car you race with. In our world toe-in is the enemy & toe-out is our friend. We always want the car to have toe-out to some degree ... statically, in bump & dynamically when turning. Always toe-out.

One key reason we do not want to "cross-over" from toe-in to toe-out or vice versa ... is the tires' slip angle goes neutral when this happens. Said another way, when you have a small amount of toe-out driving down the road, the tires have a small degree of slip angle in the tread that creates grip. Tire basics 101: No slip angle = no grip. If the bump steer of your car causes the tires to go from toe-out to toe-in ... for a brief bit of time when the tires were right in-between ... they didn't have grip. The feel in the steering is lightness. This is bad.

The same happens if go the other direction from toe-in to toe-out. So the moral of this story is we want to stay one side of the toe equation at all times. For Grandma Nelly's Delta 88 Cruiser, make sure it toes-in ALWAYS. But for our hot rods we're tracking, road racing or autocrossing, we need to make sure we're always in a state of toe-out.

There are crude ways & precise ways to do bump steer on your race car. How precise you do it probably depends on your commitment level to performance of your car. We use the Joes' bump steer measurement system on that makes the job quicker, easier, repeatable & more accurate. But it can be done less expensive ways. One is to clamp a laser level horizontally on the front rotors & project a laser point forward onto a light or white surface (wall, cardboard or whiteboard).

The math is easy:

• If you place the whiteboard exactly 8' ahead of your FACL, divide the amount you see by 4.

• If you place the whiteboard exactly 10' ahead of your FACL, divide the amount you see by 5.

• If you place the whiteboard exactly 12' ahead of your FACL, divide the amount you see by 6.

• If you place the whiteboard exactly 16' ahead of your FACL, divide the amount you see by 8.

The farther out you go, the more accurate you will be, but you gotta work with the space you have in your garage/shop. 8' & 16' make the fractions easier to do math with. Here are "example instructions."

With the shocks & springs out of the car, jack the spindle up to exactly ride height relative to your chassis. (Measure this before you take the car apart) Shoot the laser ahead onto a whiteboard 8' ahead of FACL & make a mark.

Now compress the suspension exactly 1" from ride height & make another mark on the whiteboard. Do this again at 2", 3" etc ... whatever you plan to travel your car in dive ... and make a mark on the whiteboard at each point. The amount of toe-out or toe-in will look exaggerated due to the 8' distance.

For example, let's say your numbers look like this ... & do the math.

• At 1" dive from ride height you gain 1/4" toe out ... divide by 4 & you actually have 1/16" bump-out

• At 2" dive from RH you gain 5/8" of toe out ... divide by 4 & you actually have 5/32" bump-out

• At 3" dive from RH you gain 1" of toe out ... divide by 4 & you actually have 1/4" bump-out

Let's Talk Toe, Bump & Ackerman

Toe-Out ... How Much? Bump-Out ... How Much? Ackerman ... How Much?

Good questions with no common answer that fits every car. I do have a good rule of thumb for each I've developed over the years.

I start with Ackerman. If you read the grip section of this Forum site, you know WHY we're running Ackerman is to mechanically turn the inside front tire to achieve optimum grip. If you haven't read that yet, you should, to understand the importance of Ackerman in our steering.

How much Ackerman we need depends on how well we're working the inside front tire of the particular race car. Roll angle plays a big role in this. The flatter we get the car to run, the better it works the inside front tire & the less Ackerman we need to mechanically twist the tire to achieve optimum slip angle on the inside front tire (and therefore grip).

As a starting point ONLY, from my racing experience, my Ackerman guideline is:

• If the car is rolling less 0.5° or less (Max) we need 25-40% Ackerman

• If the car is rolling around 1.0° we need 50-70% Ackerman

• If the car is rolling around 2.0° we need 80-100% Ackerman

• If the car is rolling more than 3° the Ackerman doesn't matter, as the inside front tire isn't loaded anyway.

For static Toe-Out & Bump-Out, if we have enough Ackerman & especially if the Ackerman is tunable, then I have a very basic toe setting of 1/8" Toe-Out (Total) at ride height & bump-out each side 1/32" AT MY TARGET DIVE NUMBER for a total of 1/16" bump-out. This gives us a total of 3/16" toe-out in full dive under braking ... just before we turn the steering wheel into the corner. *Obviously the toe-out increases dramatically as the Ackerman does its job.

Just for conversation sake with cars in the 105-110" wheelbase zone & track widths around 60" ... 100% Ackerman will have the inside front tire turned "about" 6° more than the outside front tire. Ackerman of 75% would be around 4.5°, 50% around 3°, 25% around 1.5°. You get the general idea.

But, if we can't get enough Ackerman in the car, we can "cheat it" with a little additional static toe-out & a lot more bump-out. The most I've EVER ran on a short, tight road course was 1/4" of toe-out & 1/4" of bump out on a POS car with zero Ackerman.

I know people that have ran an inch of total toe-out & bump-out in autocross cars. It worked, and by worked, I mean the car was better than not running big toe-out ... but that's not the right way to do it. Getting the Ackerman right & running smaller toe-out & bump-out is MUCH faster, more consistent & doesn't kill tires.

Next topic : Rag Joints ... WTF?

Rag joints in steering column assemblies is purely for street cruiser comfort. The goal of a rag joint is to use the layer of rubber & fibers to isolate the driver from the road.

Why in the name of all that is holy and sacred in racing would we want to do that? We do not ... as they cause delay in steering response & isolate the driver from feeling what the tires are doing & how the car is handling.

Yes, I sell a rag joint for my clients that use their muscle car as a daily driver & cross country touring car. They have different goals. But for high performance & race cars, we want to throw these rag joints as far as we possibly can & replace them with an actual coupler or u-joint.

Bump Steer at the Steering Arm

If you're running an OEM Factory spindle, it has a tapered hole for the OEM type outer tie rod end to bolt to. The OEM style outer tie rod end is non-adjustable for height so, we want to change to rod ends & either use a bolt or tapered bump steer stud kit for attachment. Nothing wrong with utilizing a bump steer stud kit, like the one shown below, if you find one to fit your factory spindle.

Obviously the tapered end bolts into the steering arm. Then the cylindrical end utilizes spacers & shims for you to adjust your outer tie rod end to achieve your desired bump steer. Combine this with a racing centerlink with adjustable height pivot posts & slugs. Those two should allow you to achieve a pretty good bump steer curve.

Use the Large OD SAE washer (purple circle) & the regular nuts (green circle) we supply for taking on & off many times while adjusting your bump steer. Use the full height Aircraft Nylock Nuts (blue circle) for final assembly.

Quick Tips:

If we want more Toe-Out in dive:

* Raise inner tie rod end pivot at rack or centerlink, or lower the outer tie rod end with spacers.

If we want less Toe-Out in dive:

* Lower pivot at rack or inner tie rod end at centerlink, or raise the outer tie rod end with spacers

Our standard "Pro Bump Steer Bolt Kit" includes 3.50" 12-point bolts & an assortment of spacers & shims to dial in your bump steer. If you find your car need longer bolts & more spacers, we have 4.00", 4.50" & 5.00" kits we can send you at no charge. The 4.00" & 4.50" kits replace the .250" tall tapered spacers with .625" tall tapered spacers. If you need over 2" of spacer, our 5" kit includes two tapered steel spacers 2.00" tall (See image below), plus all the regular shims & smaller spacers. No extra charge if you need either of the longer kits.

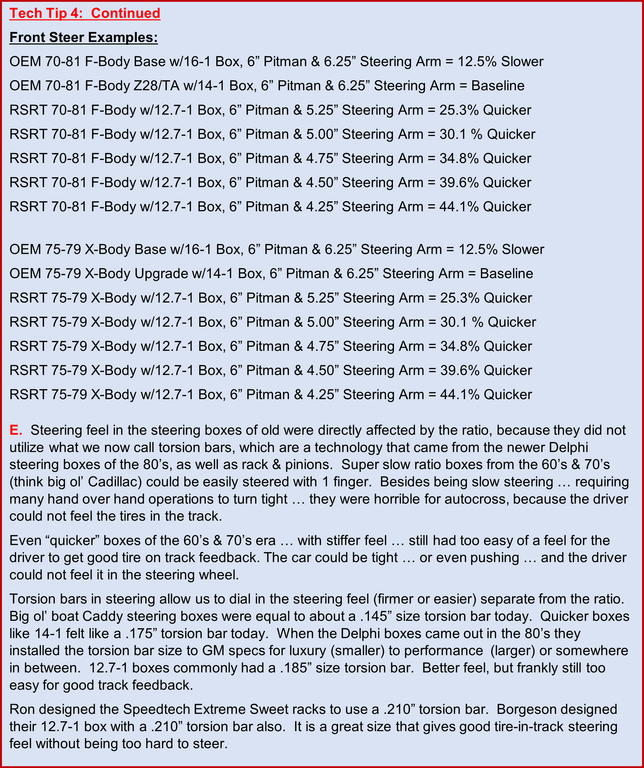

Lastly, if you're running RSRT spindles, don't sweat the ratio in the steering box being 12.7-1 or 14-1. All RSRT Spindles utilize shorter steering arms that are slotted. Your kit comes with 0, .250" & .500" Offset Slugs for a Steering Arm Range of 4.25"-5.25" in 5 steps. The effective arm length is in the 4.9" to 5.9" range when we rotate the spindle to the 10-10.5° target caster we run. You can fine tune the slugs to make the steering moderately quick to super quick to suit your personal preferences.

#46

Front Suspension & Steering Geometry for Track & Racing / Re: Front Suspension & Steerin...

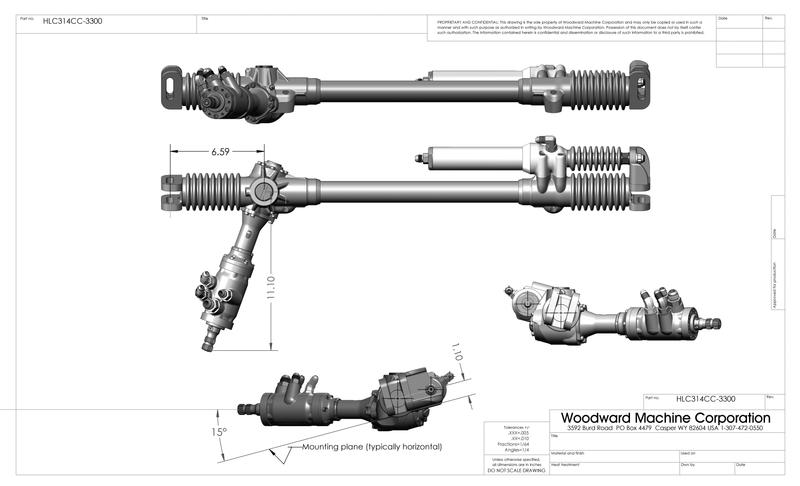

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 10, 2026, 01:44 PMLet's Talk Steering Box & Drag Link Systems

Steering:

• You can stay with the steering box & centerlink style or switch to Rack & Pinion. Both

have pros & cons.

• The R&P is lighter & more compact. The steering box & centerlink style is stronger &

has more, easier adjustability.

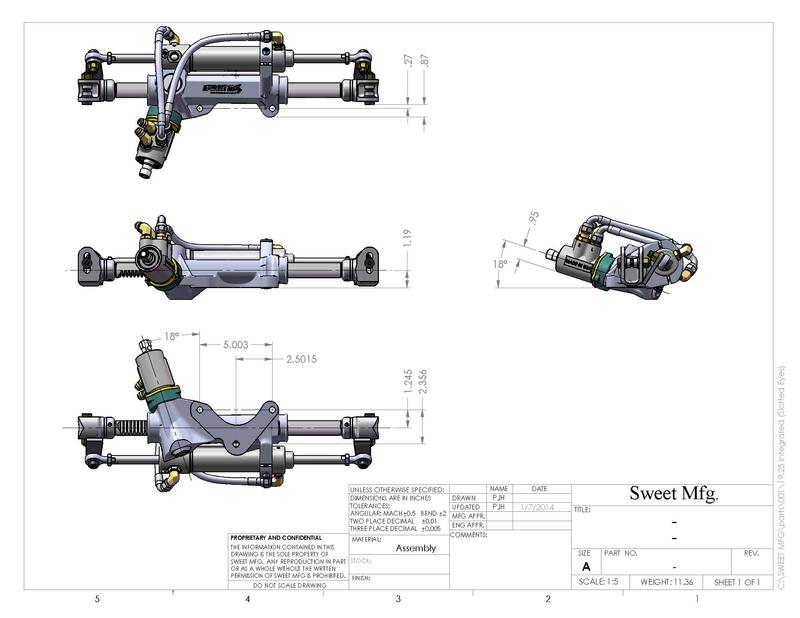

• If you go R&P, consider the race versions with adjustable ends from Woodward or

Sweet.

• If you go steering box style, get away from the older Saginaw steering boxes. The technology has advanced & those old boxes have soft gears to intentionally wear out quicker.

• Consider the Delphi 600 series box, rebuilt from one of the racing companies, or the new units from Borgeson. Both of these utilize the latest steering box technology. They have a torsion bar inside, like a rack, to set the steering feel. The .210" torsion bar is a great starting point.

• Lastly, you'll want an adjustable, race quality centerlink & idler arm plus a good steel pitman arm.

This is personal preference. I am a fan of super fast steering when I have a smooth handed driver.

But to figure out how fast or slow a steering system is ... you have to look at the four major things dictating that ...

#1 Steering box ratio

#2 Steering arm length

#3 Pitman Arm Length

#4 Steering wheel diameter

Most standard steering boxes are rated in ratios, but they convert easily:

8-1 = 3" per turn

10-1 = 2.75" per turn

12-1 = 2.5" per turn

14-1 = 2.25" per turn

16-1 = 2" per turn

18-1 = 1.75" per turn

20-1 = 1.5" per turn

If the ratio is from the OEM, the pitman length is included in this equation. If you're buying a racing box & it's called an 8-1, you may want to confirm what length pitman arm they referenced & the pitman arm length you plan to run. You can do the math and figure out how many turns of the steering wheel you have, or need, and compare it to different combinations.

I'd love to say all spindle & steering arm combinations turn a set degree with no other variables. But we all know ... they are always other variables. Inner tie rod end location plays a role in the math. When the inner tie rod ends line up with the outer tie rod ends ... both fore & aft and up & down ... the steering rack or centerlink movement will produce the highest spindle steering degree. But ... when the inner tie rod ends are locating ahead of or behind the outer tie rod ends ... we will see slightly less spindle & steering arm turning degree. Same when the inner tie rods are at different heights than the outer tie rod ends. I'm not trying to make this more complicated than it is. I just want you to know simple math on paper can be close, but not accurate in every situation. For this reason, I always use software.

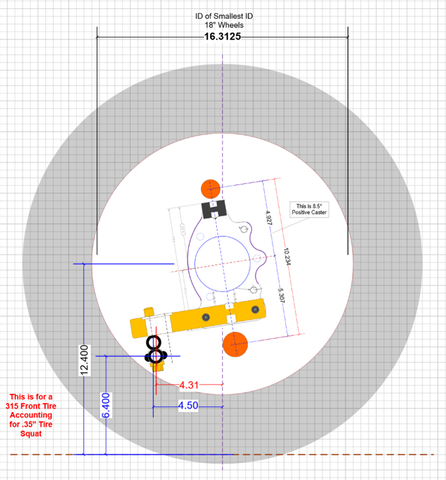

Back at the Ranch, again, when we're building a new front suspension from scratch, and the packaging parameters allow us to fit in a great rack & pinion, like our Sweet or Woodward Road Racing racks ... in the correct location for optimum Ackerman ... that's the best way to go. That's not to say ANY Rack & Pinion is better than a good steering box system. No way. Most OEM racks & aftermarket racks copied from of OEM racks ... suck. They don't have the power nor the strength to handle today's cars with 315 or larger front tires. Heck, the super common 79-93 Mustang rack fails in cars with 275 front tires. I've seen those guys bringing not one, but two spare racks to the track.

Most OEM racks are too wide. The C6-C7 Corvette rack & pinion is a good piece. But it is way too wide to work in applications any narrower than the C5/C6/C7. When we put a rack with the pivots too wide in a car the bump steer curve is ugly as #$@*&. Yes, you can get one point of the travel to hit your target bump steer number ... but the travel on either side of that number is funky. We should never run a rack that has the pivots at the wrong width for good bump steer characteristics. Nor is "ok" to put a rack in the wrong location, where Ackerman suffers.

So again, if we're designing something from a clean sheet of paper, to be bad ass, like our Track-Warrior front clips or the Speedtech Extreme clips & chassis I designed that use the right width Sweet Road Racing rack ... then great. Otherwise, if the car came with a steering box that utilizes a centerlink, pitman arm & idler arm linkage ... we are BETTER OFF to get that system right, than to swap in a weak ass rack in the wrong location.

There is NOTHING wrong with the performance of a steering box system ... if we get everything trued-up, equal & optimized. They did NOT come that way from the factory. GM, Ford & Chrysler had different priorities than we do. The next section will tell you & show you exactly what to do to true up & equalize your steering box & steering linkage.

#47

Front Suspension & Steering Geometry for Track & Racing / Re: Front Suspension & Steerin...

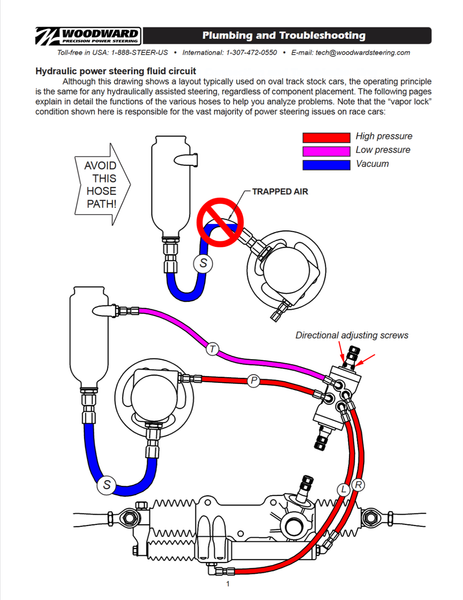

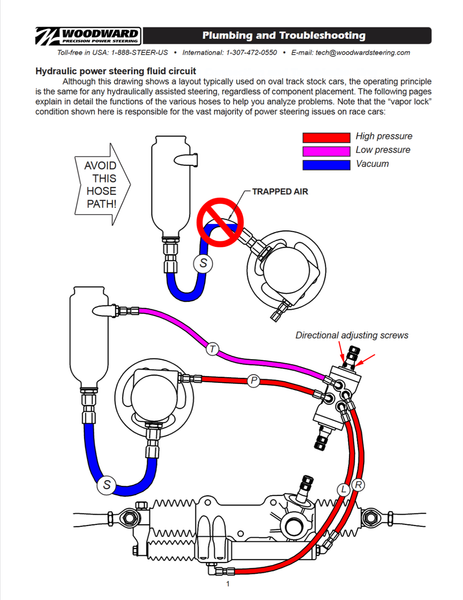

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 10, 2026, 01:39 PMRack Plumbing:

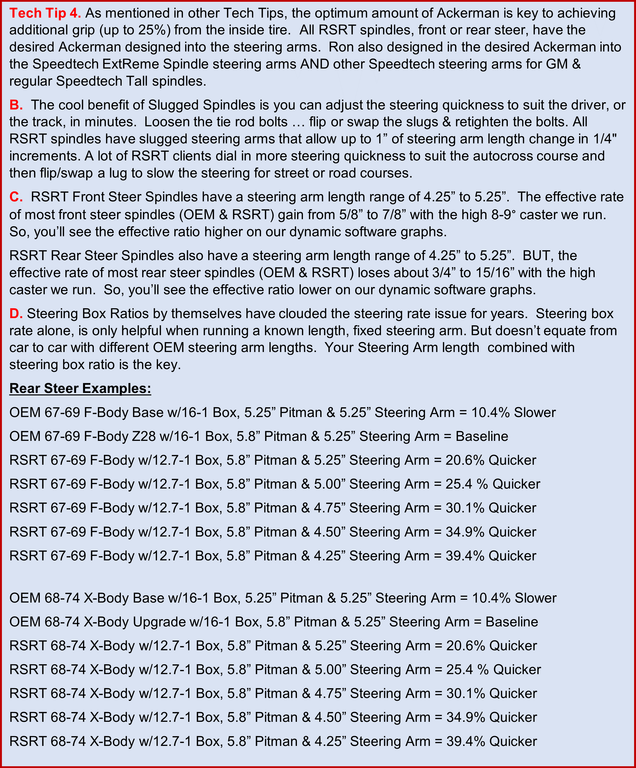

The diagram from Woodward above shows what not to do, and how to do it right. I will add in a large, baffled reservoir solves a lot of issues. The wrong power steering fluid causes a lot of issues ... leaks & poor performance. The Woodward illustration & text below show what having the wrong fluid does to seals.

Rack Installation:

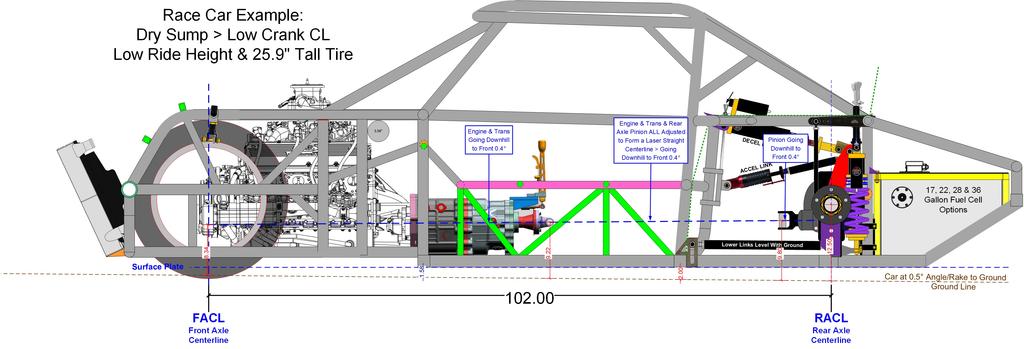

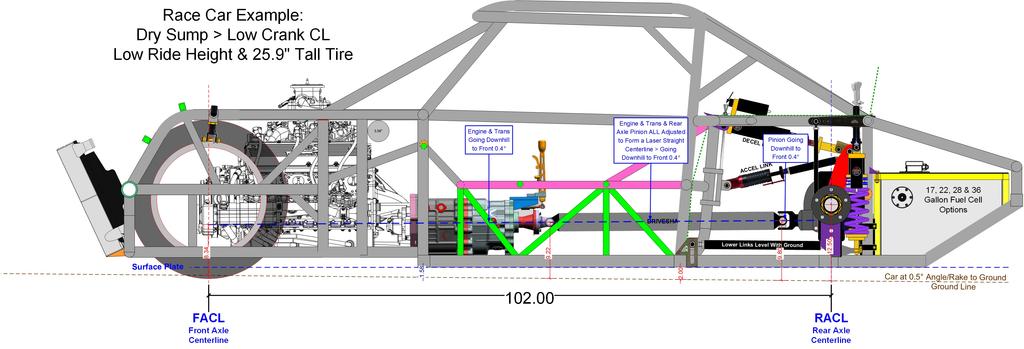

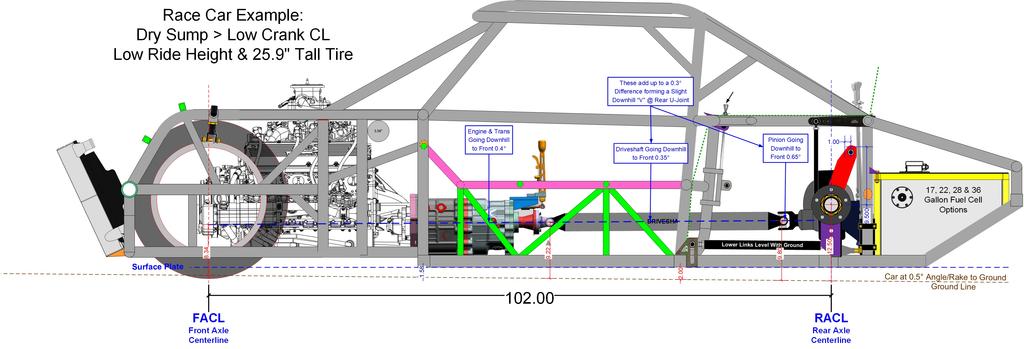

Keeping this simple, because each application will have its own unique needs. Assuming front steer, moving the rack back towards the FACL, increases Ackerman & moving it forward away from the FACL decreases Ackerman. Rear steer is just the opposite. We make the rack mounts on our Track-Warrior chassis slotted, so the car owner has about 1/2" fore & aft range of Ackerman tuning.

Adjusting Ackerman with a Rack is quite easy, although there is not always room to do so. The engine can be in the way. When I'm designing new chassis or front clips, the engine location has to be known beforehand. Since the location of the heavy engine & trans ... fore & aft, up & down ... play a huge role in the car's CG location ... we have to give the engine location priority.

Many, many ... too many ... road racing series limit how far back the engine can go to the #1 spark plug at the FACL. Well crap. That places the front of the damper or pulleys 6.5" or more ahead of the FACL. That makes the rack 8" or more ahead of the FACL. Not good for Ackerman. There are things we can do to get some Ackerman back, but a rack that far ahead of the FACL sure makes it hard. So I love designing race cars with the engine back ... far ... faaar back. In our GTX, GSX, GTL & GTF chassis & clips, we place the #1 plug 8.75" to 9.00" behind the FACL. That gives us two get benefits ... a race car that is 50/50 F/R weight bias ... and rack location to achieve whatever Ackerman we want. But those pesky race series rules.

Raising the rack leads to a bump steer curve with more "bump-out" ... meaning more toe-out during bump steer in dive.

Lowering the rack leads to a bump steer curve with more "bump-in" ... meaning more toe-in during bump steer in dive. The opposite is true in lift.

Getting the bump steer to be happy & do what we want is a LOT of work, because if we change one thing, the other key items go out of whack. Getting the optimum rack width, or centerlink inner tie rod pivot width, is a big key to achieving a happy bump steer curve. That is why I designed the new AXT-Star Centerlink with centerlink inner tie rod pivot points that can moved in or out, as well as up or down.

The challenge is, if we move the rack or centerlink pivots up or down, forward or rearward, the optimum width CHANGES. So, in designing a steering package, we have to get the window for engine & oil pan clearance nailed down first. Then we need to test combinations of height & width of the pivot points until we achieve the best scenario.

Changing the suspension parameters changes the optimum steering parameters. If we take a package optimized to travel X.xx" in dive & X.x° ... with optimum steering ... and then move the control arm and/or ball joint pivots to optimize roll center & camber for a different travel and/or roll target ... we throw that optimum steering out the window. The bump steer can not stay optimum if we adjust the control arm and/or ball joint pivots. So, all of this needs to be worked out as a total combination, which all RSRT suspensions & steering have been. If you want to change the dive or roll of your RSRT package down the road, we will work with you to get the steering re-optimized.

Rack Length:

This is pretty straight forward, but overlooked by those not in the know. Rack length obviously determines where your inner tie rod pivots are and how long the effective tie rods end up being. This plays a HUGE role in your bump steer curve. The length of the rack should be chosen to achieve your target bump steer curve. Any other reason is bullshit.

Achieving the Optimum Bump Steer Curve with a Rack:

When we're building a new front suspension from scratch, and the packaging parameters allow us to fit in a great rack & pinion, like our Sweet or Woodward Road Racing racks ... in the correct location for optimum Ackerman ... that's the best way to go.

That's not to say ANY rack is better. No way. Most OEM racks & aftermarket racks copied from of OEM racks ... suck. They don't have the power nor the strength to handle today's cars with 315 or larger front tires. Heck, the super common 79-93 Mustang rack fails in cars with 275 front tires. I've seen those guys bringing not one, but two spare racks to the track.

Most OEM racks are too wide for race car applications. The C6-C7 Corvette rack & pinion is a good piece. But it is way too wide to work in applications any narrower than the C5/C6/C7. When we put a rack with the pivots too wide in a car the bump steer curve is ugly as #$@*&. Yes, you can get one point of the travel to hit your target bump steer number ... but the travel on either side of that number is funky. We should never run a rack that has the pivots at the wrong width for good bump steer characteristics. Nor is "ok" to put a rack in the wrong location, where Ackerman suffers.

In general, if we want more Toe-Out in dive:

* Raise pivot at rack or inner tie rod end at centerlink

* Or lower the outer tie rod end

In general, if we want less Toe-Out in dive:

* Lower pivot at rack or inner tie rod end at centerlink

* Or raise the outer tie rod end

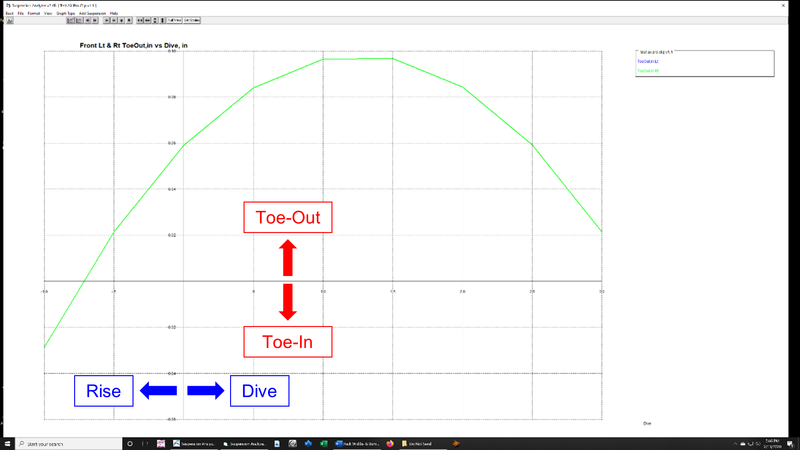

A lot of Racers bump steer the car wrong. The most common mistake is checking & setting the bump steer at maximum travel each way, up & down (Rise & Compression). Who cares what the bump steer is at 4" of compression travel ... if your target dive travel is 3"? When I'm working out the bump steer curve for race cars, I set my measuring parameters ... either on the car or in software ... based on the target dive amount ... and the expected rise amount above ride height.

Let's talk dive first, because that is the priority. If I know we're going to dive the race car 2-5/8" ... I'll calculate how much further the outside tire will travel with chassis roll taken into account. If I'm working in software, like Performance Trends, I don't have to calculate anything. I just put the car in a dynamic state with 2-5/8" dive, whatever body roll I'm targeting & add in a set amount of steering (I usually do 15°) ... and read how much travel the outside front tire traveled.

If I'm working without software, bump steering a car in the shop, I use a rough guide to help me, which is 1° of chassis roll is about 1" of travel difference. This is dead on accurate at 57" track width, which is surprisingly close to the 54" to 60" track width of so many road race cars. If I need to calculate the exact amount, just run the percentages like so. If the track width is 60" ... which is 3" greater than 57" ... the math is 3 ÷ 57 = 5% ... so .95" of travel difference is 1° chassis roll with a 60" track width. 1.05" would be the travel difference for a 54" track width.

When I say "1 inch of travel difference" ... that means the outer tire & wheel will compress 1/2" more than the actual front end dive amount (at the chassis centerline) and the inner tire & wheel will compress ½" less. So after the math, I add the 1/2" to the target dive of 2-5/8" to know the highest travel in dive is 3-1/8". That is where I want to bump steer each side if the car. Make sense?

I have a go to baseline for toe-out & bump steer, assuming I have a good front end design & I can get the Ackerman I want. My baseline is 1/16" static toe-out per side, 1/8" static toe-out total. Then at my target dive, I want to see 1/16" more total toe-out, for a dynamic toe out total of 3/16" ... before we turn the steering wheel. Obviously, when we turn the steering wheel, Ackerman comes into play. On a side note, in race lingo we'd say this race car has 1/8" of bump out in dive.

If I'm working on a race car where I can not achieve the Ackerman I want, I will increase the amount of bump-out in dive to help the Ackerman. This is not ideal, but frankly the down side of tiny increased tire friction under braking is pretty minimal.

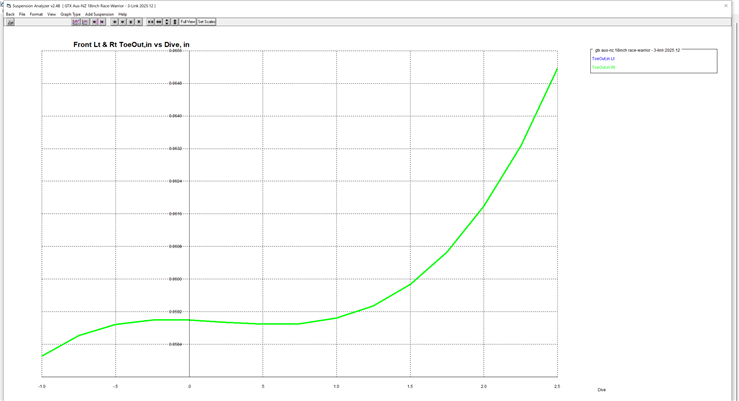

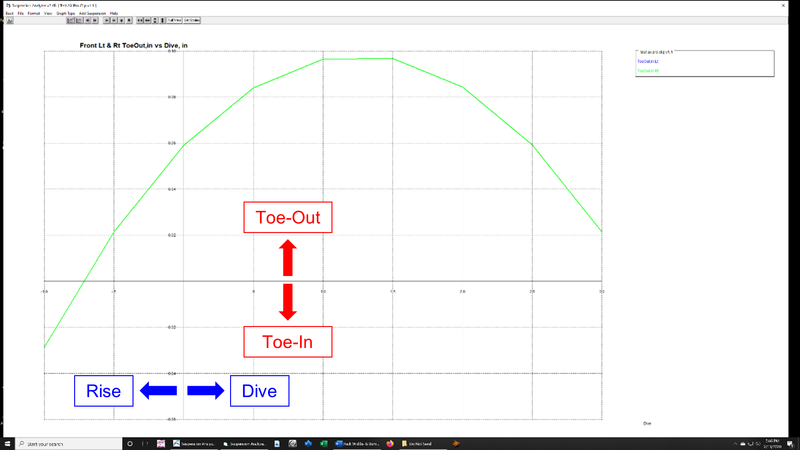

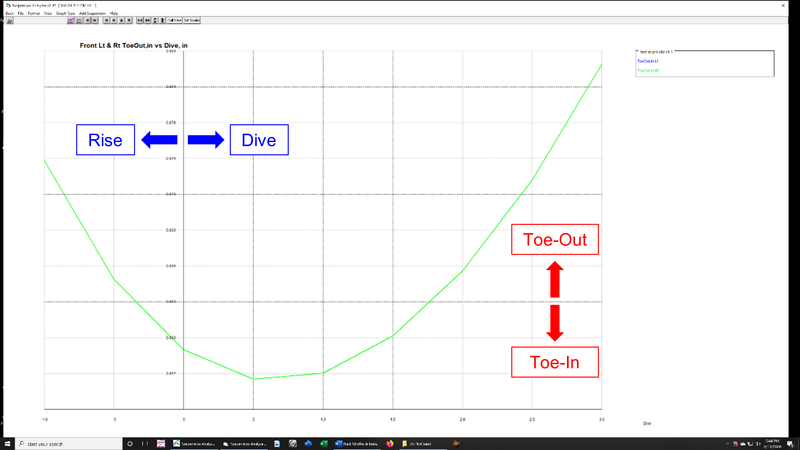

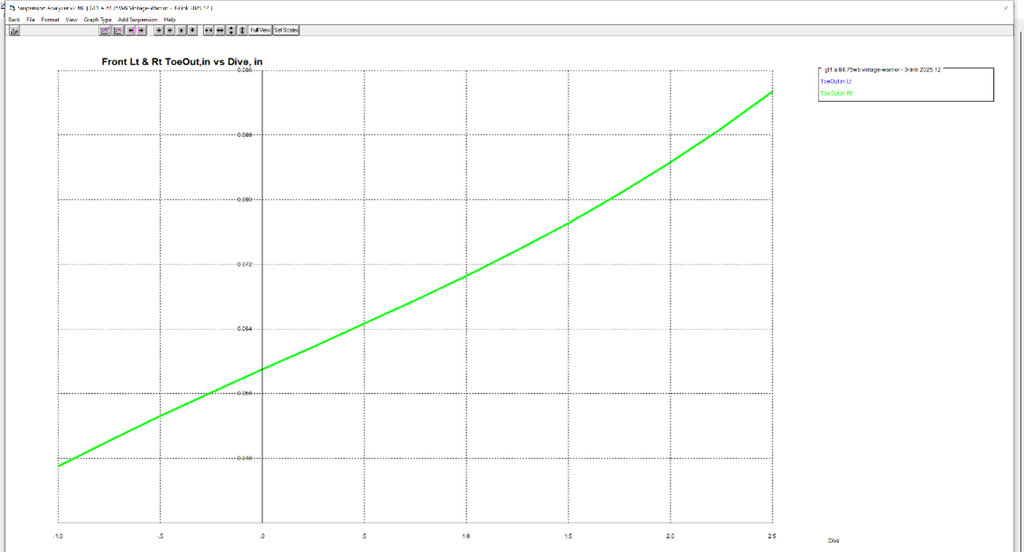

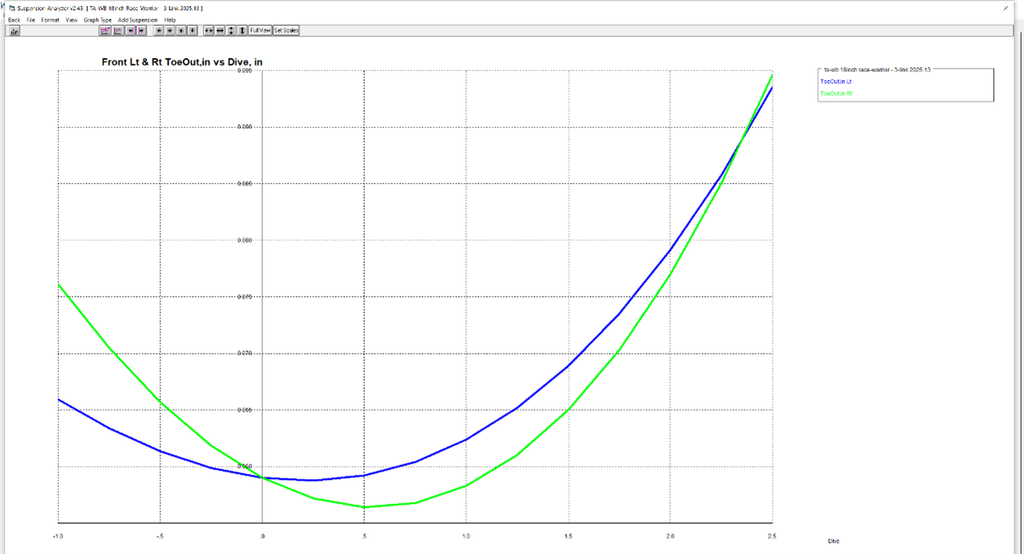

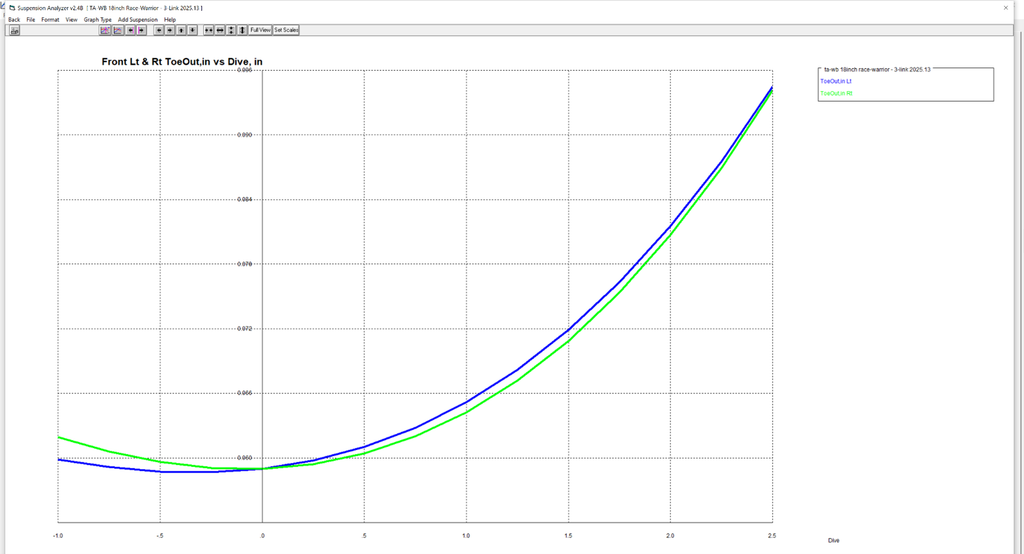

Now let's talk about bump steer "curves" ... not just the bump steer amount. You hear that term "bump steer curve" ... but what does it really mean. Well look at the two bump steer graphs below & you'll see they have two very different curves. Neither one is good. Just a starting point for our discussion.

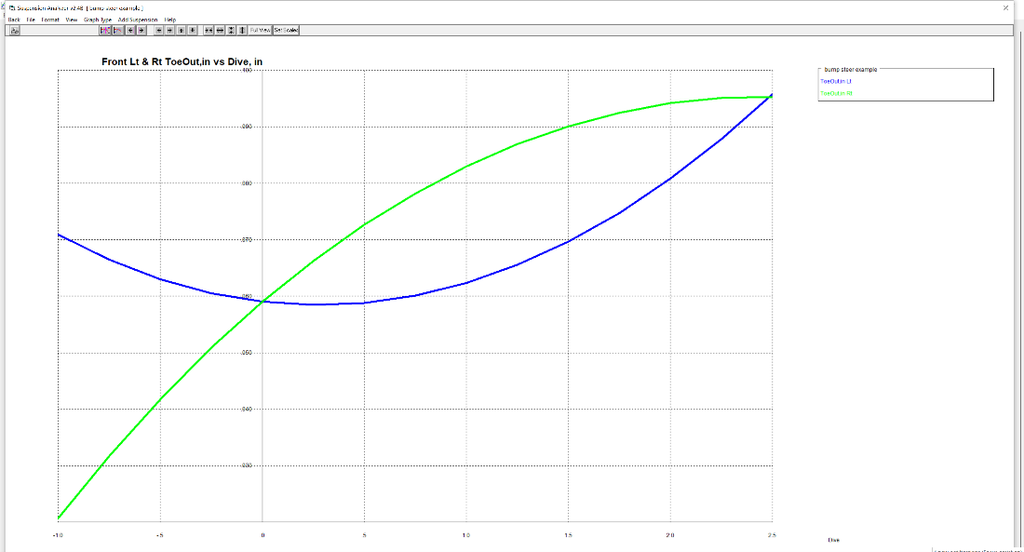

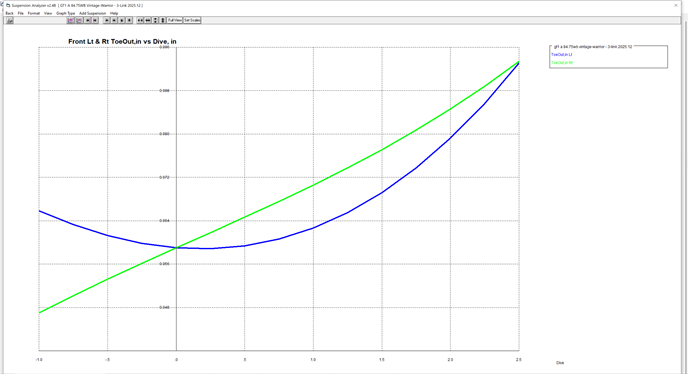

Look at the bump steer graph above. If the bump steer shows toe-IN in rise (from ride height), then toes OUT initially in dive ... and then toes back IN with further dive = the Rack or Centerlink mounting points for the inner tie rods are too narrow. Being wider would help straighten out your bump steer curve.

Look at the bump steer graph below. If the bump steer shows toe-OUT in rise (from ride height), then toes IN initially in dive... and then toes back OUT with further dive = the Rack or Centerlink mounting points are too wide. Being narrower would help straighten out your bump steer curve.

Now, what does a good bump steer curve look like? I think we have to be realistic in our expectations. We're working in a box of parameters set by rules, priorities & strategies. Rules often determine where the engine is, which affects where the rack is. Rules determine ride heights, which affects our choice of dive travel strategy. Getting your splitter on the ground & the CG as low as possible may take higher priority than what the bump steer curve looks like. But we should work as hard & long as it takes with different rack lengths & heights to achieve the best bump steer curve we can.

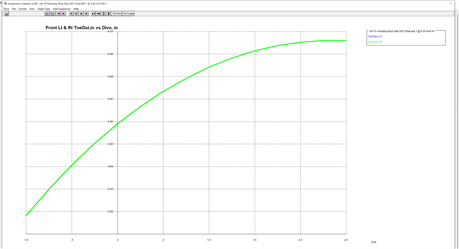

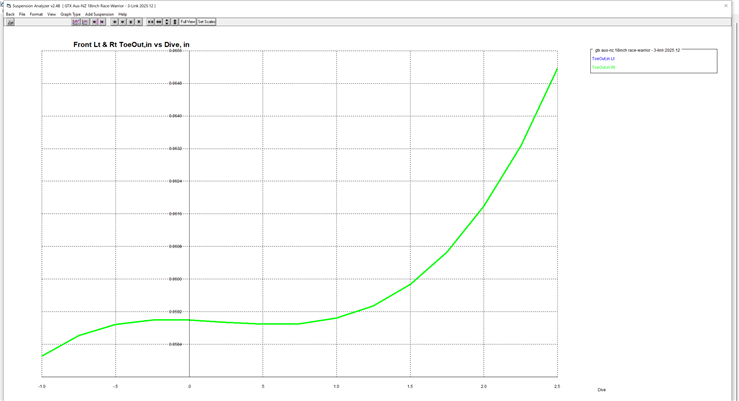

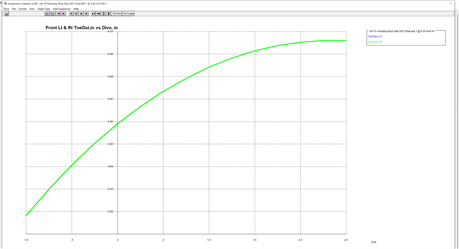

The image below shows a very sweet green bump steer curve. I'll break it down. The first inch of dive is basically zero bump steer. So is the first 1/2" of rise. We have an 1.5" of zero bump steer to keep the tire contact patches stable & happy over rough stuff. Then, in full dive, under hard braking, we have the bump-out we want to help the Ackerman. And if we were to have the race car rise above ride height (rare with our shocks & aero) the toe-out reduces a little. Absolutely beautiful curve.

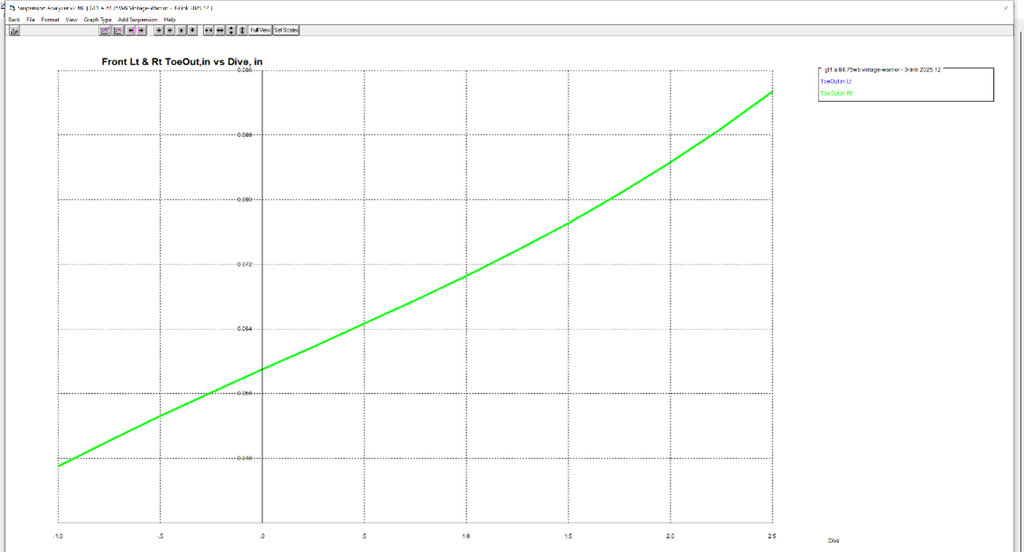

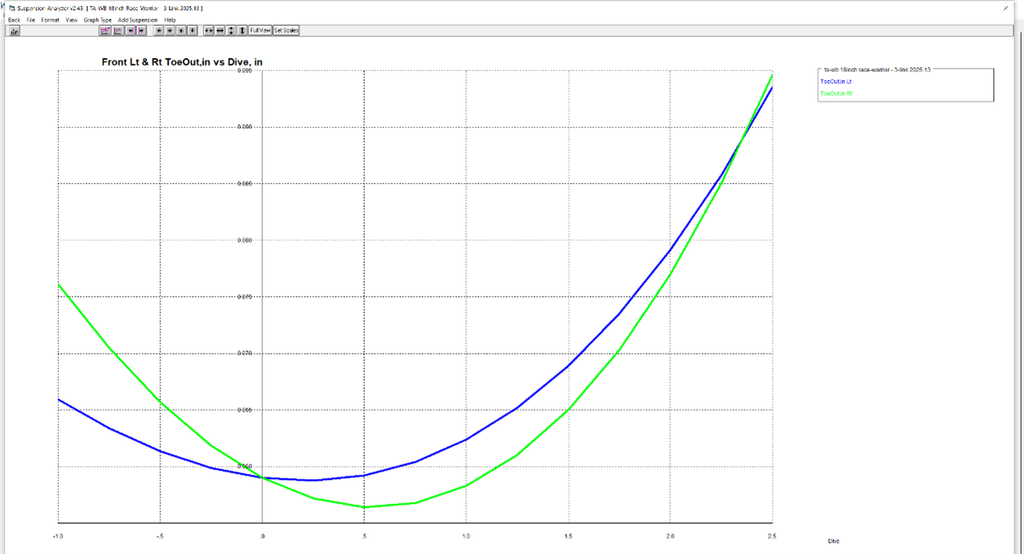

Most of my Race-Warriors have this curve above. But frankly a couple don't. It is not always possible. Especially if we don't have the ability to change the rack width, or enough range of mounting location. Moving on to another example below. The green line shows almost straight all the way. Some people think if the line is straight it must be all good. When I see this, I know the rack is the wrong width. In this case it was 23.25" wide. The green bump steer curve in this car changes too much, too quick with this setup. We need to run the software with a lot narrower rack & find a better curve.

See image below. This is with a 19.25" rack. Yes, 4 " narrower. The green curve is the same as above. The blue curve is the 19.25" rack. Again, we want that first 1/2" or more of compression travel to be gentler in the bump-out change. The tire needs it.

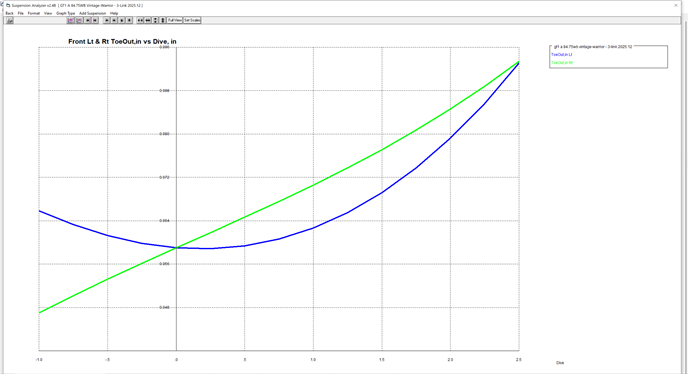

I hate the green bump steer curve in the graph below. The bump-out in this car changes horribly quick with this setup. But it's the best you can do sometimes if you're stuck with the wrong width rack or centerlink. This happens to be a Mustang, rear steer, steering box car with a centerlink 18.5" wide at the inner tie rod pivot points.

See the blue bump steer curve in the graph below. I "fixed" the bump steer in the software by changing the centerlink to 24.0" wide inner tie rod pivot points. The problem is no centerlink is that wide at the inner tie rod pivot points. None. Nadda. There is not enough room to make one that wide. So, while this may look cool in the software, it is unrealistic in the real world, and we're stuck with the green[/b] bump steer curve in this old muscle car.

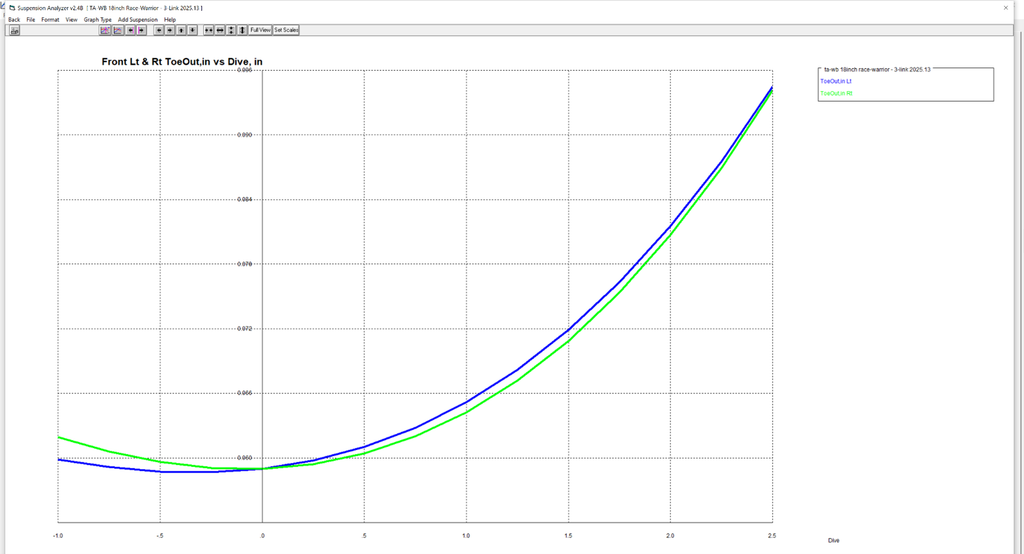

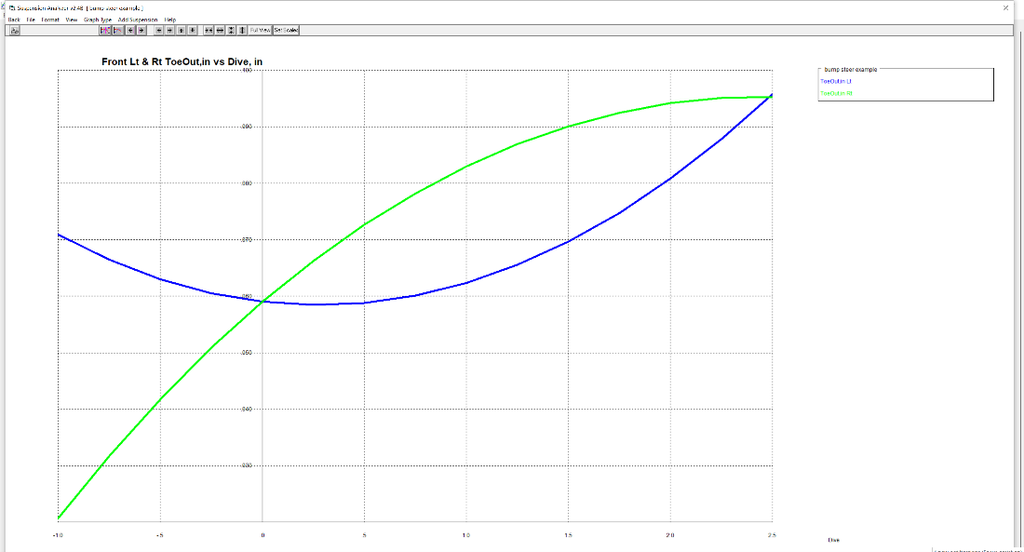

Sometimes, in the box of parameters, you can't get near perfect. You simply have to choose between the lesser of two evils. See the image below. The blue graph is not perfect by any means, but is a lot better than the green[/b] graph. The both arrive at the same bump-out target of .094" toe-out on each side. But the blue curve is gentler & does not toe IN, then Out, like the green curve.

I like to say I design race cars in the real world. By that, I mean I'm working within the parameters of what is really available to buy or have made. Steering racks for example, come in 1/4" width increments. If I end up designing a race with a XX.065" width, with a beautiful curve, what the heck is that good for? Notta. Now with a steering box & our new AXT-Star Centerlink with movable inner tie rod mounts, we can achieve fine tuned numbers, but still within the width range of the centerlink.

Here is situation (image below) where the rack difference is 1/4". The blue line represents the best bump steer curve with a 26.25" wide rack & the green line represents the best bump steer curve with a 26.00" wide rack. If we knew the race car had no aero downforce in the front, so would see rise above ride height, I'd choose the blue line setup to avoid going into as much toe-out is rise. If we knew the race car had good aero downforce in the front, so would not see rise above ride height, I'd choose the green line setup due to its slower bump-out curve.

Let me share a piece of advice to save you money & help you perform better. Pick your suspension strategy & work out your geometry before you buy your rack & pinion. Anytime you move the control arms, slugs or ball joints around, you change what is optimum for the rack length. So lock your geometry down before you buy a rack. Buying different lengths racks can hurt any budget & the incorrect length rack hurts performance.

The diagram from Woodward above shows what not to do, and how to do it right. I will add in a large, baffled reservoir solves a lot of issues. The wrong power steering fluid causes a lot of issues ... leaks & poor performance. The Woodward illustration & text below show what having the wrong fluid does to seals.

Rack Installation:

Keeping this simple, because each application will have its own unique needs. Assuming front steer, moving the rack back towards the FACL, increases Ackerman & moving it forward away from the FACL decreases Ackerman. Rear steer is just the opposite. We make the rack mounts on our Track-Warrior chassis slotted, so the car owner has about 1/2" fore & aft range of Ackerman tuning.

Adjusting Ackerman with a Rack is quite easy, although there is not always room to do so. The engine can be in the way. When I'm designing new chassis or front clips, the engine location has to be known beforehand. Since the location of the heavy engine & trans ... fore & aft, up & down ... play a huge role in the car's CG location ... we have to give the engine location priority.

Many, many ... too many ... road racing series limit how far back the engine can go to the #1 spark plug at the FACL. Well crap. That places the front of the damper or pulleys 6.5" or more ahead of the FACL. That makes the rack 8" or more ahead of the FACL. Not good for Ackerman. There are things we can do to get some Ackerman back, but a rack that far ahead of the FACL sure makes it hard. So I love designing race cars with the engine back ... far ... faaar back. In our GTX, GSX, GTL & GTF chassis & clips, we place the #1 plug 8.75" to 9.00" behind the FACL. That gives us two get benefits ... a race car that is 50/50 F/R weight bias ... and rack location to achieve whatever Ackerman we want. But those pesky race series rules.

Raising the rack leads to a bump steer curve with more "bump-out" ... meaning more toe-out during bump steer in dive.

Lowering the rack leads to a bump steer curve with more "bump-in" ... meaning more toe-in during bump steer in dive. The opposite is true in lift.

Getting the bump steer to be happy & do what we want is a LOT of work, because if we change one thing, the other key items go out of whack. Getting the optimum rack width, or centerlink inner tie rod pivot width, is a big key to achieving a happy bump steer curve. That is why I designed the new AXT-Star Centerlink with centerlink inner tie rod pivot points that can moved in or out, as well as up or down.

The challenge is, if we move the rack or centerlink pivots up or down, forward or rearward, the optimum width CHANGES. So, in designing a steering package, we have to get the window for engine & oil pan clearance nailed down first. Then we need to test combinations of height & width of the pivot points until we achieve the best scenario.

Changing the suspension parameters changes the optimum steering parameters. If we take a package optimized to travel X.xx" in dive & X.x° ... with optimum steering ... and then move the control arm and/or ball joint pivots to optimize roll center & camber for a different travel and/or roll target ... we throw that optimum steering out the window. The bump steer can not stay optimum if we adjust the control arm and/or ball joint pivots. So, all of this needs to be worked out as a total combination, which all RSRT suspensions & steering have been. If you want to change the dive or roll of your RSRT package down the road, we will work with you to get the steering re-optimized.

Rack Length:

This is pretty straight forward, but overlooked by those not in the know. Rack length obviously determines where your inner tie rod pivots are and how long the effective tie rods end up being. This plays a HUGE role in your bump steer curve. The length of the rack should be chosen to achieve your target bump steer curve. Any other reason is bullshit.

Achieving the Optimum Bump Steer Curve with a Rack:

When we're building a new front suspension from scratch, and the packaging parameters allow us to fit in a great rack & pinion, like our Sweet or Woodward Road Racing racks ... in the correct location for optimum Ackerman ... that's the best way to go.

That's not to say ANY rack is better. No way. Most OEM racks & aftermarket racks copied from of OEM racks ... suck. They don't have the power nor the strength to handle today's cars with 315 or larger front tires. Heck, the super common 79-93 Mustang rack fails in cars with 275 front tires. I've seen those guys bringing not one, but two spare racks to the track.

Most OEM racks are too wide for race car applications. The C6-C7 Corvette rack & pinion is a good piece. But it is way too wide to work in applications any narrower than the C5/C6/C7. When we put a rack with the pivots too wide in a car the bump steer curve is ugly as #$@*&. Yes, you can get one point of the travel to hit your target bump steer number ... but the travel on either side of that number is funky. We should never run a rack that has the pivots at the wrong width for good bump steer characteristics. Nor is "ok" to put a rack in the wrong location, where Ackerman suffers.

In general, if we want more Toe-Out in dive:

* Raise pivot at rack or inner tie rod end at centerlink

* Or lower the outer tie rod end

In general, if we want less Toe-Out in dive:

* Lower pivot at rack or inner tie rod end at centerlink

* Or raise the outer tie rod end

A lot of Racers bump steer the car wrong. The most common mistake is checking & setting the bump steer at maximum travel each way, up & down (Rise & Compression). Who cares what the bump steer is at 4" of compression travel ... if your target dive travel is 3"? When I'm working out the bump steer curve for race cars, I set my measuring parameters ... either on the car or in software ... based on the target dive amount ... and the expected rise amount above ride height.

Let's talk dive first, because that is the priority. If I know we're going to dive the race car 2-5/8" ... I'll calculate how much further the outside tire will travel with chassis roll taken into account. If I'm working in software, like Performance Trends, I don't have to calculate anything. I just put the car in a dynamic state with 2-5/8" dive, whatever body roll I'm targeting & add in a set amount of steering (I usually do 15°) ... and read how much travel the outside front tire traveled.

If I'm working without software, bump steering a car in the shop, I use a rough guide to help me, which is 1° of chassis roll is about 1" of travel difference. This is dead on accurate at 57" track width, which is surprisingly close to the 54" to 60" track width of so many road race cars. If I need to calculate the exact amount, just run the percentages like so. If the track width is 60" ... which is 3" greater than 57" ... the math is 3 ÷ 57 = 5% ... so .95" of travel difference is 1° chassis roll with a 60" track width. 1.05" would be the travel difference for a 54" track width.

When I say "1 inch of travel difference" ... that means the outer tire & wheel will compress 1/2" more than the actual front end dive amount (at the chassis centerline) and the inner tire & wheel will compress ½" less. So after the math, I add the 1/2" to the target dive of 2-5/8" to know the highest travel in dive is 3-1/8". That is where I want to bump steer each side if the car. Make sense?