Recent posts

#51

Rear Suspension & Geometry for Track & Racing / Re: Rear Suspension & Geometry...

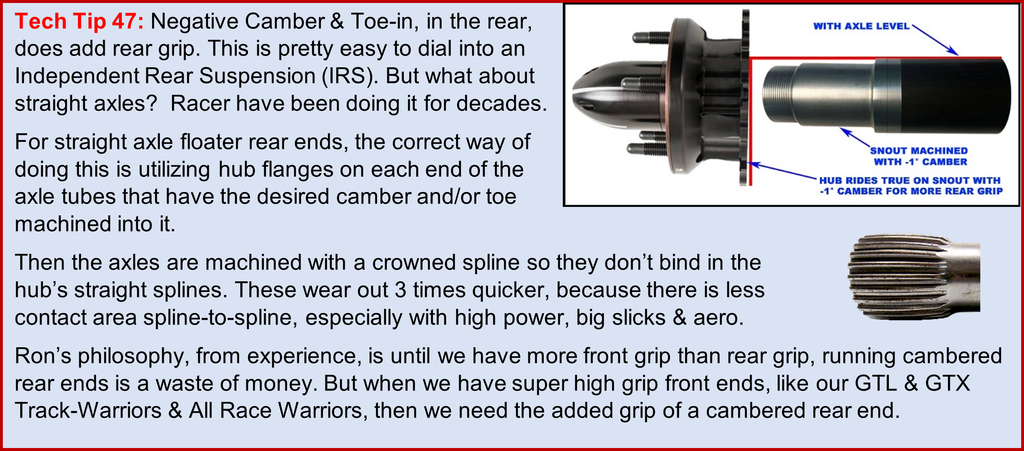

Last post by Ron Sutton - Dec 22, 2025, 12:35 PMCambered Rear Ends:

First, so everyone is on the same page, Racers & Manufacturers use the term "Cambered" in

this instance of rear end housing ends ... regardless if we end up with a camber change or a

toe change on the rear tires. In my comments, I will use the appropriate term, so it's clear in

everyone's minds.

Second, which way you mount the "cambered hubs" to angle the tires ...of the four common

options ... in at top for negative camber ... in at front for toe-in ... or in at back for toe-out ...

or some combination of camber & toe ... is dependent on your tuning goals.

Third, how much ... as in how many degrees do you do any of these ... can be dependent on

tire slip angle & chassis roll angle.

Let's discuss what each does ... why you would care ... and go from there.

1. Negative camber of the rear tires ... in small amounts ... would help the outside rear tire run with a flatter contact patch, giving it more grip. Just as in the front end, camber helps the contact patch of the outside tire & hurts the contact patch of the inside tire, by tipping it the wrong direction.

The outside rear tire is loaded more, so it "rolls under" more than the inside rear tire. If you add just enough negative camber to the rear tires to optimize the outside rear tire's contact patch ... you won't hurt the contact patch & grip of the inside rear tire too much. The gain in grip on the outside rear tire will exceed the loss of grip on the inside rear tire, netting an overall grip increase. Besides ... you need to disengage the inside rear tire to a degree anyway, to get the car to turn.

How much rear negative camber is optimum for you varies with race car factors. Higher g-forces and/or heavier race cars benefit from higher negative camber settings up in the -1.5° to -2.0° range. Lower g-forces and/or lighter race cars benefit from lower negative camber settings up in the -1.0° to -1.5° range.

Adding a cambered rear axle MAY make sense, providing you feel you need more rear tire lateral grip & you can afford to buy axles & drive plates 3-4 times more often. In my racing experience, with adjustable rear suspensions, I've only found it beneficial to add more rear lateral grip IF the FRONT END had more grip than the rear was capable. This is pretty rare. We only experience that in our GTX & GTL Track-Warriors & our Race-Warriors.

Looking at it another way, if we can get all the rear grip you need to match the front & achieve neutral, balanced handling, why would we pay more money to get a cambered setup we can't fully use & we have to buy axles & drive plates 3-4 times more often? There are applications where it makes sense, just not all application.

On Track-Warriors, I prefer to buy a slightly larger rear wing than we need & trim it out for handling balance. In class racing with our Race-Warriors, we're already running the maximum wing the rules allow. So, we need to assess if a cambered rear end would be beneficial.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2. Toe-in of the rear tires ... add slip angle to the outside rear tire (in whatever corner). This makes the outside rear tire achieve optimum slip angle sooner ... have grip sooner ... and provide a sense of security sooner on corner entry. This is quite common in road racing, as it builds confidence in the driver. But there are some negative side effects. In my opinion, the side effects are not be worth it, except rare situations

Side effects:

a. The outside rear tire gets to the optimum slip angle at a lower corner speed, reducing that tire's ultimate corner speed capability.

b. The toe-in of the two rear tires ... say 1° each for a total of 2° toe-in ... creates unwanted scrubbing of the rear tires driving around the track. This builds heat, misleading the crew into thinking they're working the rear tires more than they actually are.

c. The poor inside rear tire is turned the opposite direction for optimum slip angle, and therefore has less grip throughout every section of the corner.

d. Toe-in of the rear tires reduces the rear steer effect of slip angle. That rear steer effect is needed to offset the counter steer effect the slip angle produces in the front end. So, we may end up with a tighter race car ... prone to pushing & understeer.

From my racing experience, I feel rear toe-in is a band-aid for old design, tall sidewall tires that had very high optimum slip angles ... and/or cars with a rear heavy weight bias that need additional grip on initial corner entry. About the only time I want rear Toe-In is on race cars with no rear aero.

3. Toe-out of the rear tires ... reduces the initial slip angle. This makes the outside rear tire achieve optimum grip later at a higher speed ... and respond later ... so the car may feel loose on entry. But the outside rear tire gets to the optimum slip angle at a higher corner speed, increasing that tire's ultimate corner speed capability. I have personally seen this work out in two different situations.

One was with a highly effective, dual element rear wing that was too much. The road race car was pushy, even on high speed corners. Adding the Toe-out made the car faster than no toe-out. Had we tried this on a race car with too little downforce, we'd just learn what it costs to repair the rear of race cars.

The second time it worked, is on a race car that the front end wouldn't turn well. Prior to testing with toe-out in the rear, the car was fine on high speed corners but too tight on low speed corners. So added rear toe-out helped the race car turn better in low speed corners. On the high speed stuff, they just increased the Angle of Attack (AoA) of the rear wing to balance the race car in the fast sweepers. Again, it did work well. But each situation it did was unique.

On most race cars, adding toe-out still makes the outside rear tire achieve optimum slip angle later ... have grip later ... but it provides a sense of "oh shit I hope it catches" on corner entry. In my opinion, the scary side effects of rear toe-out make it a "no-go" in most cases. If your race car won't turn well, let's work on the front end or simply free up some rear grip.

Do NOT CONFUSE this with what WAS quite common in NASCAR oval racing for awhile. They toed BOTH rear wheels to the right, a couple degrees. It helps the car turn better & carry more mid-corner speed. You could clearly see the cars "crab-walking: down the straight aways. It is/was NOT for the faint of heart, as the car would turn in quick & feel like the rear wasn't going to stick, but it did.

I have a lot of tricks I use in building winning cars. For oval track, especially with the rear weight heavy NASCAR Modifieds we raced & the high front scrub radius we had ... running negative rear camber & both hubs toed right was a bit faster. But definitely not comfortable for every driver.

#52

Rear Suspension & Geometry for Track & Racing / Re: Rear Suspension & Geometry...

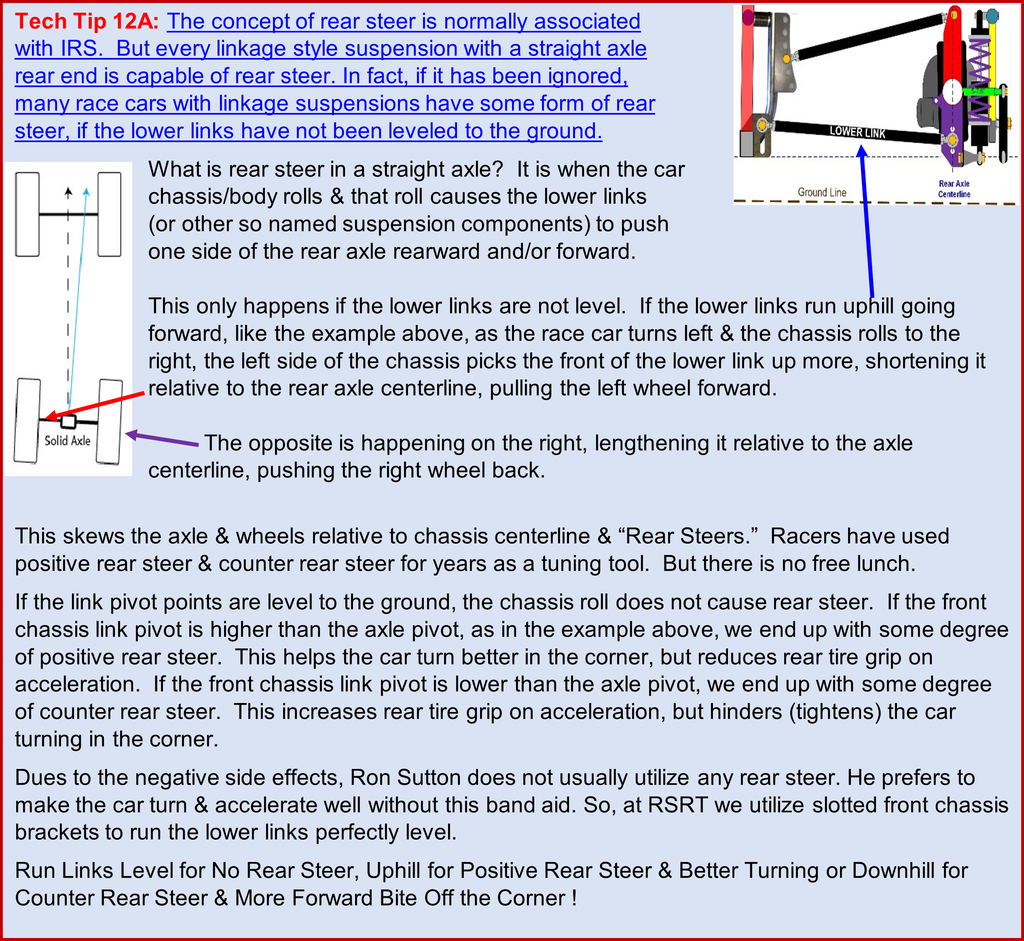

Last post by Ron Sutton - Dec 22, 2025, 12:33 PMRear Roll Steer with Straight Axle Rear Suspensions:

Let's discuss Rear Roll Steer & it's effects on traction. First the basics:

• Lower links at an angle running uphill going forward creates a Positive Rear Steer effect as the body & chassis roll during cornering. Larger uphill link angles produce higher degrees of Positive Rear Steer.

• As the car achieves roll angle, the Positive Rear Steer effect helps the car to turn more while cornering, by pushing the outside tire rearward, the inside tire forward and both tires pointing to the outside of the corner. This is Positive Rear Steer. This also adds a loosening effect. How much depends on the degree of roll steer.

• Lower links at an angle running downhill going forward creates a Counter Rear Steer effect, by pushing the outside tire forward, the inside tire rearward and both tires pointing to the inside of the corner. This is Counter Rear Steer. Larger downhill angles produce higher degrees of Counter Rear Steer.

• As the car achieves roll angle, Counter Rear Steer effect decreases the car's turning ability. This adds a tightening effect. How much depends on the degree of roll steer.

* This next explanation does not apply to drag cars if they have controlled their body rotation with preload, springs and/or sway bars. This applies to all other cars that run on Road Courses, AutoX. Street, etc ... where you are trying to accelerate out of corners under power.

Even though running the lower links at an uphill angle ... applies more force applied to lifting & planting the tires harder ... there is also the different action of rear steer happening simultaneously ... providing a counter effect. The small gain in traction from increased lifting force (for a shorter duration) is over powered by the more powerful rear steer effect loosening the car up. The typical result is more grip at throttle pick up, but loss of traction at some point trying to exit the corner under power.

When the loss of traction occurs ... it is defined by how much Positive Rear Steer is in the car and how long the corner exit is (therefore how long cornering grip must be maintained). On tight corners it possible to achieve a setup that provides rear steer, while maintaining adequate exit grip. I find small amounts of rear steer on short, small corners, can work well, as long as everything else is optimized.

We run into problems is when we:

• Get greedy with the amount of rear steer utilized.

• Run any Positive Rear Steer on high speed, long sweeping corners.

For these reasons, I suggest:

• Positive Rear Steer can be good tuning tool for autocross & short road courses with small tight corners.

• Avoid any Positive Rear Steer on big tracks or road courses with long, fast sweepers.

• In fact, Counter Rear Steer may be used effectively on tracks with primarily long, fast sweeping corners.

#53

Rear Suspension & Geometry for Track & Racing / Re: Rear Suspension & Geometry...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Dec 22, 2025, 12:31 PMRear Roll Centers

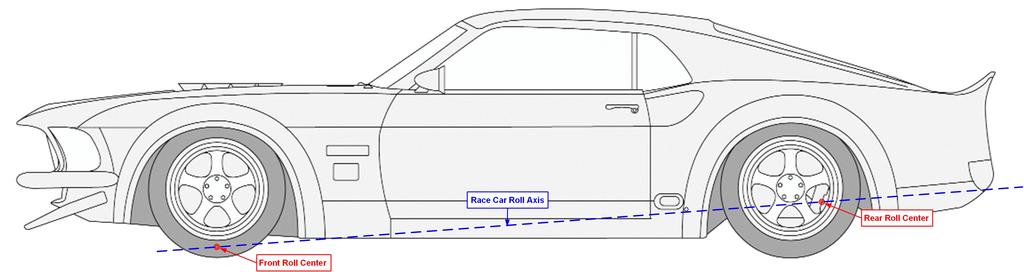

I'll be very basic for any readers following along that are completely new to this & apologize in advance for boring the veterans with more knowledge of this. Cars have two roll centers ... one as part of the front suspension & one as part of the rear suspension. I'll first explain what role they play in the handling of a car ... then how to calculate the rear roll center ... and finally how to optimize it.

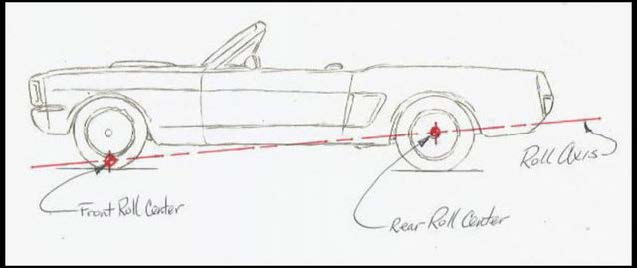

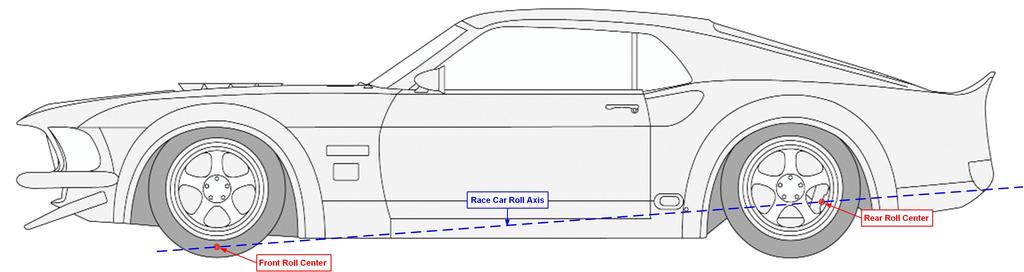

Think of the front & rear roll centers as the car's side-to-side pivot points. When the car experiences body roll during cornering ... everything (the car's mass) above that pivot point (roll center) rotates towards the outside of the corner ... and everything below the pivot point rotates the opposite direction, towards the inside of the corner. Because the front & rear roll centers are often at different heights, the car rolls on different pivot points (roll centers) front & rear ... "typically" higher in the rear & lower in the front.

If from the side view (Mustang Image below) you were to draw a line front the front roll center to the rear roll center ... this is called the roll axis ... that line would represent the pivot angle the car rolls on ... again "typically" higher in the rear & lower in the front. What you see below in the Mustang is a side view of a sample Roll Axis.

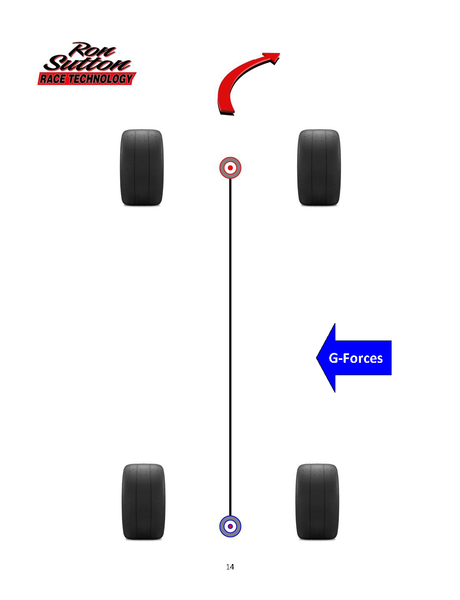

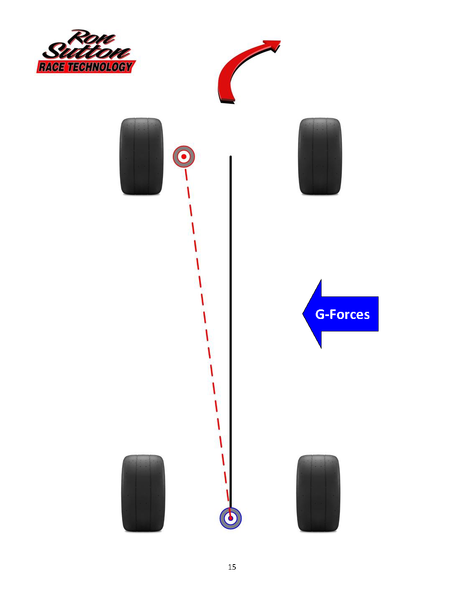

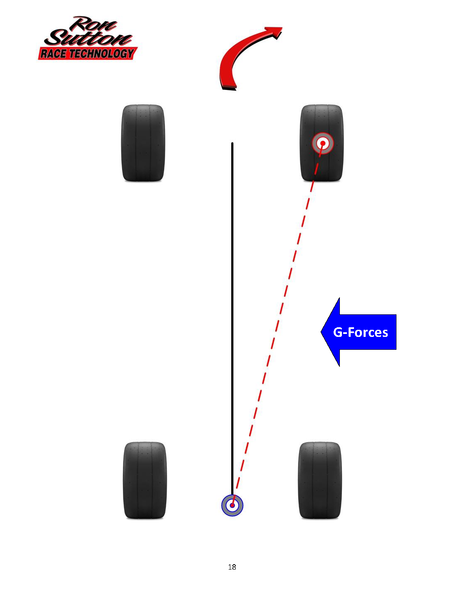

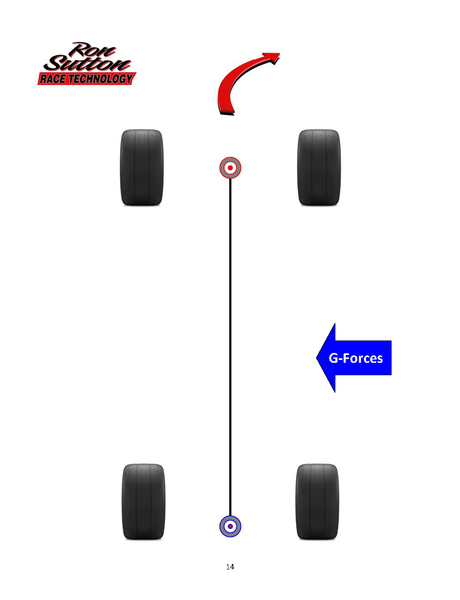

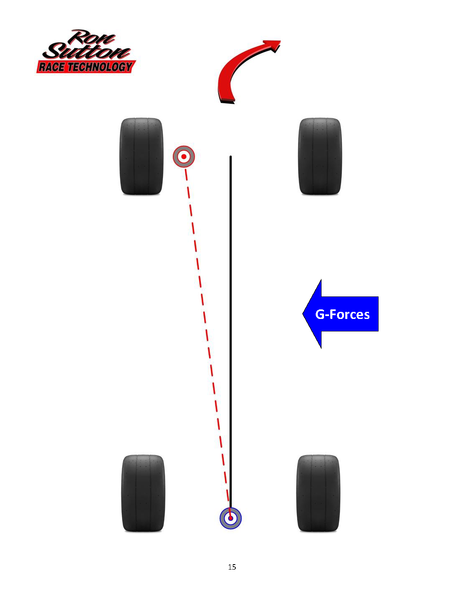

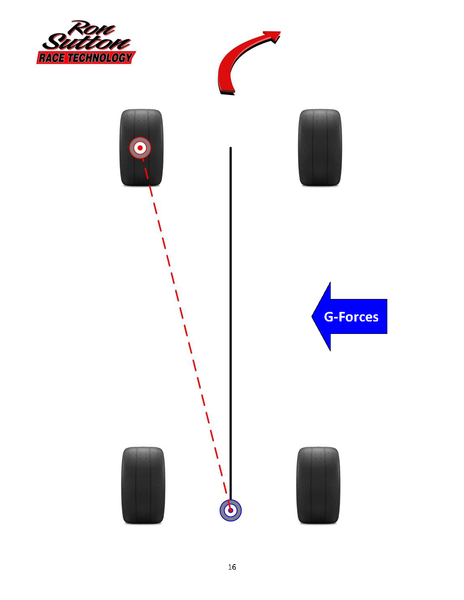

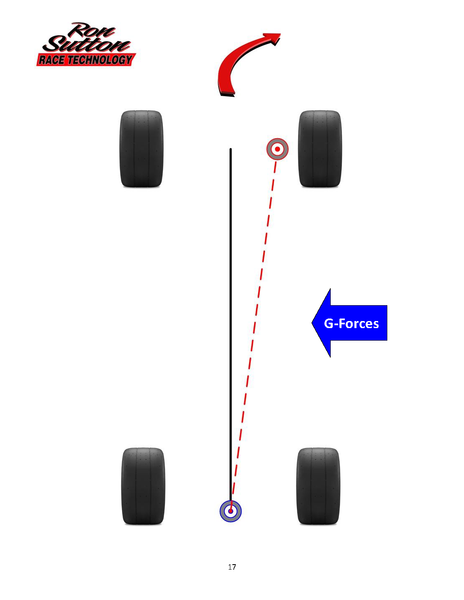

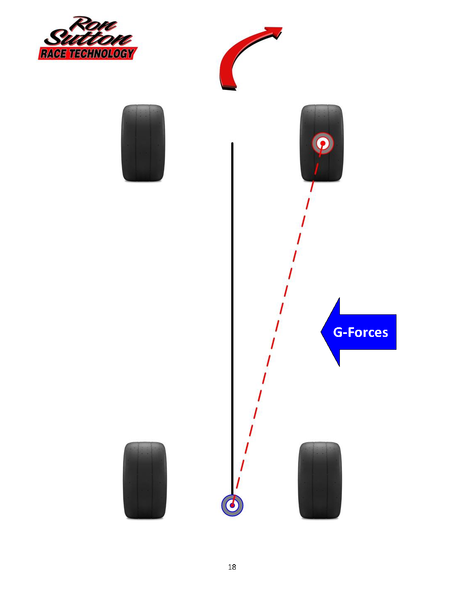

If from the top view (see below) you were to draw a line parallel down the middle of the car connecting the two roll centers ... this is what the roll axis looks like in a top view ... assuming the roll centers are actually in the middle of the race car. See image below. That line represents the pivot angle the car rolls on ... again assuming the roll centers are actually in the middle of the race car ... as well as higher in the rear & lower in the front. In so configured.

The forces that act on the car to make it roll ... when a car is cornering ... ... act (push) upon the car's Center of Gravity (CG). With the race cars we're focused on, the CG is above the Roll Center ... acting like a lever. The distance between the height of the CG & the height of each Roll Center is called the "Moment Arm." Think of it as a lever. The farther apart the CG & Roll Center are ... the more leverage the CG has over the Roll Center to make the car roll. Excessive chassis Roll Angle is your enemy, because it over works the outside tires & under utilizes the inside tires.

Some people like to look at the car as a unit. I look at it as two halves ... front & rear ... because they rarely roll the exact same.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Finding the Rear Roll Center with IRS:

Measuring all the pivot points in the front suspension to calculate the Roll Center in the rear suspension of a double A-arm suspension car can be tedious ... but the concept is quite simple. (Same as the front)

Your UCA & LCA have pivot points on the chassis ... and they pivot on the spindle at the BJC's. Forget the shape of the control arms ... the pivots are all that matter.

If you draw a line through the CL of the UCA pivots & another line though the CL of the LCA pivots ... they will intersect at some point (as long as they are not parallel). That point is called the instant Center (IC) ... and the UCA/Spindle/LCA assembly travels in an arc from that IC point. However far out that IC is ... measured in inches ... is called the Swing Arm length. More on this later.

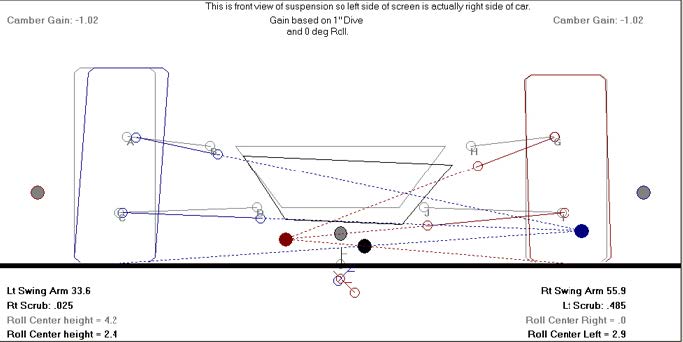

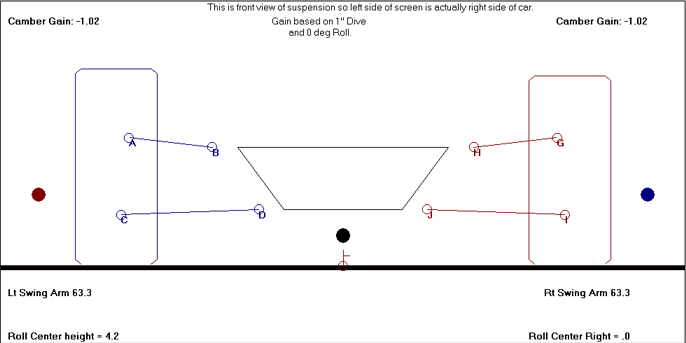

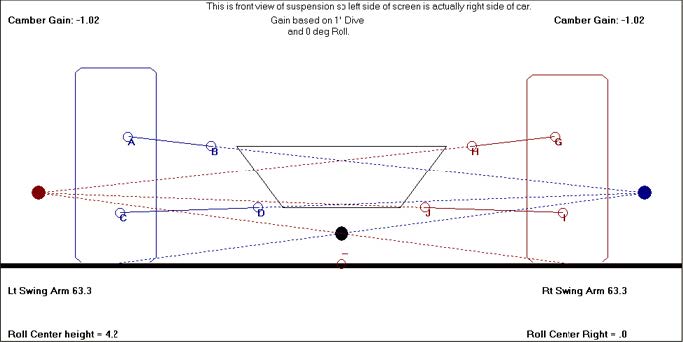

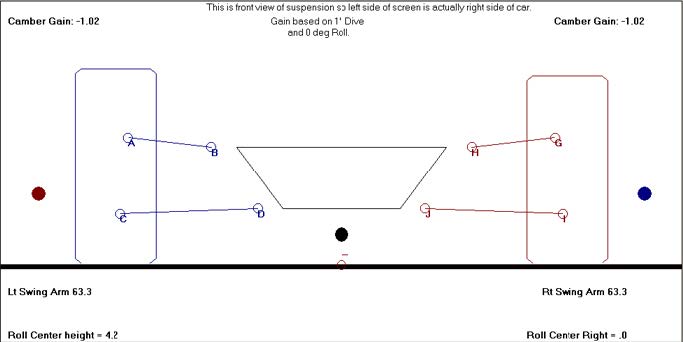

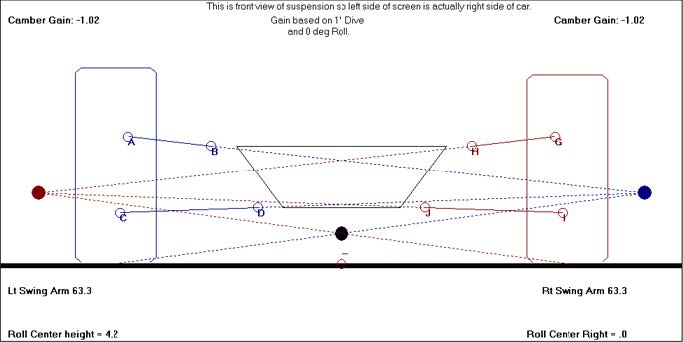

Next you draw a line from the CL of the tire contact patch at ground level ... to the IC. Do this on both sides ... and where the two "Tire CL-to-IC" lines intersect ... is the rear Roll Center. Look at the drawing below. The colored dots represent the IC for the same color LCA/UCA. The black dot represents the Static RC at ride height.

Make sense?

I do not "track tune" the rear roll center on IRS.

No different than the front suspension, if I have the rear IRS geometry happy in every way, I don't tune on the rear roll center at the track ... unless I missed the setup by a long way. Think about it. To tune on the rear roll center of an IRS, you're unbolting control arms from the chassis & changing offset slugs ... or changing ball joint heights ... or both. It's not that we can't do that at the track. I don't want to. Not only is a lot of F'n work, but I'm messing with my anti-squat %, camber gain & roll steer.

The exception would be is if my setup was waaay out to lunch & needed a complete make over. Otherwise for a small rear roll center tuning change? No sir. Notta. Not happening. I'll be tuning with spring rates, shock tuning, sway bar rates & maybe aero depending on what speeds I needed to adjust the car's handling at. Learn more in the section.

Finding the Rear Roll Center with a Straight Axle:

Panhard Bar/Track Bar: Stock car racers call it a Track Bar. I and many other racers call it a panhard bar. Different names for the same thing. Its first purpose is to locate the rear axle in the chassis (side-to-side) and allow the rear axle to travel up, down & articulate without binding up.

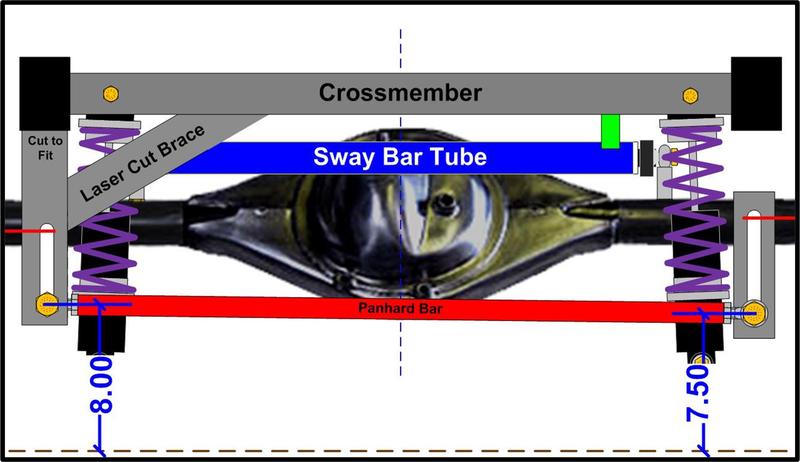

It's second purpose is to define the Rear Roll Center. The RRC is located horizontally & vertically at the center of the two pivots. If the bar is level and both sides are 8" off the ground ... the roll center is 8" above the ground. The RRC is only centered in the chassis, if the panhard bar is centered in the chassis. If you have a car with a Panhard Bar, you might want to check that.

Surprising to most Racers, a level panhard bar will NOT produce an identical handling race car on left & right hand corners. Stated another way, a level panhard bar will make the car handle differently on LH & RH corners. It makes the race car freer on right hand corners & tighter on left hand corners.

If we want the car to handle exactly the same on left & right hand corners, you will find from testing, the axle mount side needs to be a little lower than the chassis mount side. I always start with the axle mount side 1/2" lower than the chassis side & track tune from there. If the bar is at an angle with one side at 8" & the other at 7.5" ... the RC is at 7.75" ... and I am pretty close to identical handling left & right.

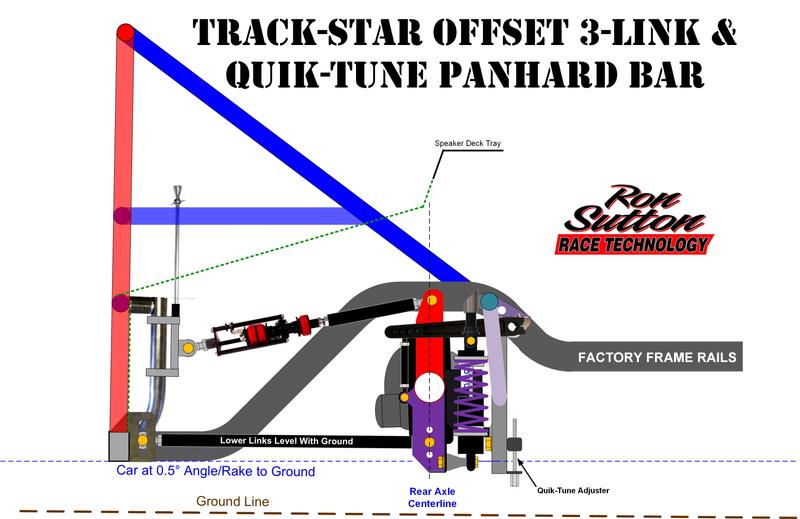

The RRC is located horizontally exactly in the center of the two panhard bar pivots ... which is why it makes sense to have the bar centered in the chassis on track, road race & autocross cars ... so the RRC is centered in the chassis. Some oval track cars use an offset J-bar on the Driver's side and therefore the RRC is offset to the Driver's side.. But that helps them load the left rear on corner exit.

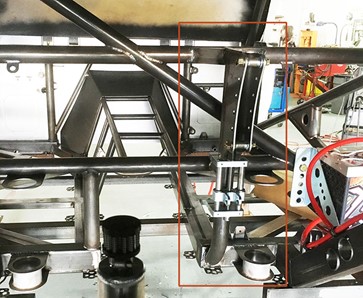

The panhard bar system shown above is "Double Adjustable", meaning both sides can be raised and/or lowered. To me, this is critical. To me, this is the starting point for adjustability, as I couldn't imagine either side being fixed (non-adjustable). This one above is the least expensive route & the most work. It uses slots. So, the bolt must be loosened, adjusted & retightened on both sides.

If you can afford it, having Quik-Tune stuff makes your life so much easier. I have found for most Racers, if a tuning change is difficult to do & time consuming, it often doesn't get done. Conversely, if a tuning change is easy to make & quick, it gets done. So, everywhere possible, I design in quick & easy suspension tunability.

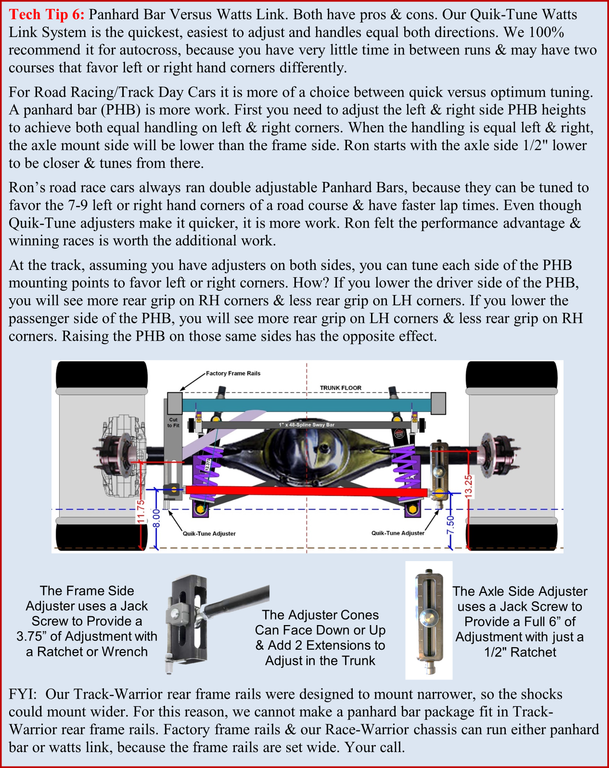

On the Double Adjustable Panhard Bar (DA PHB) system shown below, both adjusters utilize Jack Screws & Extensions up through the trunk, to make adjusting both sides of our PHB quicker & easier. This particular one utilizes the best Jack Screw adjuster on the Passenger side & a "good" add-on Jack Screw adjuster on the Driver side. The Driver side adjuster is the best one we offer that mounts to production car (over the axle) rear frame rails.

In some of our Track-Warrior & all our Race-Warrior packages, we offer a choice of Quick-Tune Watts link or Quik-Tune Double Adjustable Panhard Bar System with the best Jack Screw adjusters on both sides. But it only fits on underslung type frame designs, with an upright tube to clamp the Driver's side unit. (See below) Obviously, it is more expensive, but open the truck lid (deck lid?) & you can adjust both in seconds.

As mentioned in Tech Tip #6 above, I prefer a panhard bar over a Watts Link, because I am tuner. I'm looking for near perfection in the pursuit of having the fastest, best handling race car. Not only does a Double Adjustable panhard bar let me tune the RRC & left/right rear tire loading ... but a PHB system allows us to move the fuel cell 3 inches forward, closer to the rear axle. That's 250# moved 3 inches forward for best polar moment control.

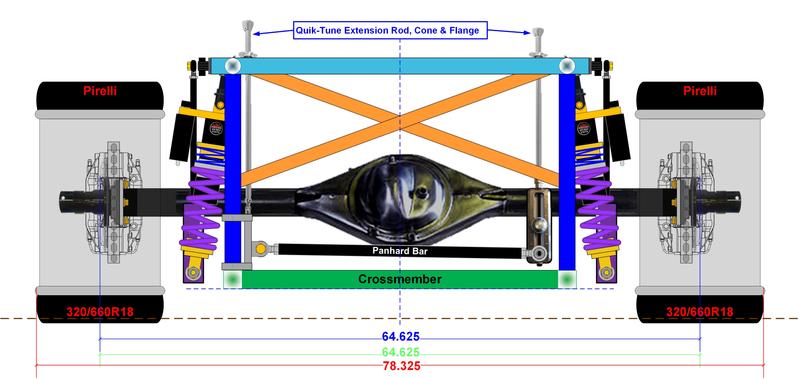

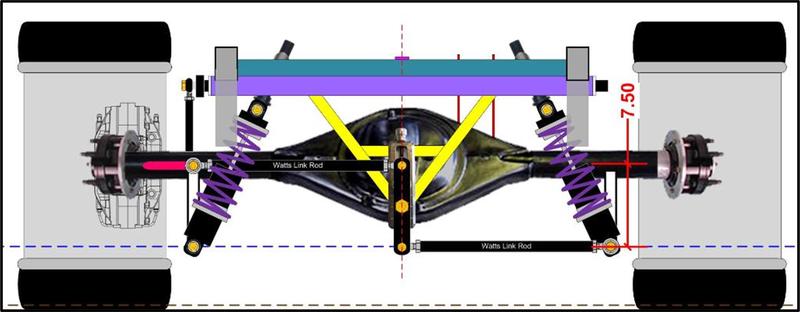

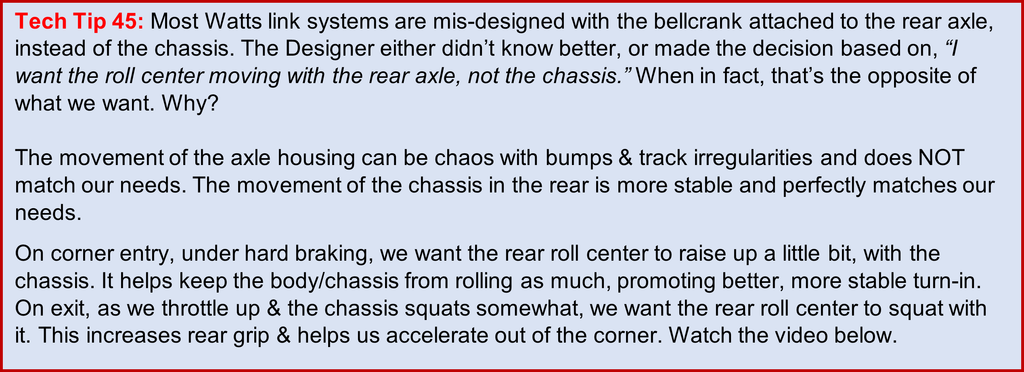

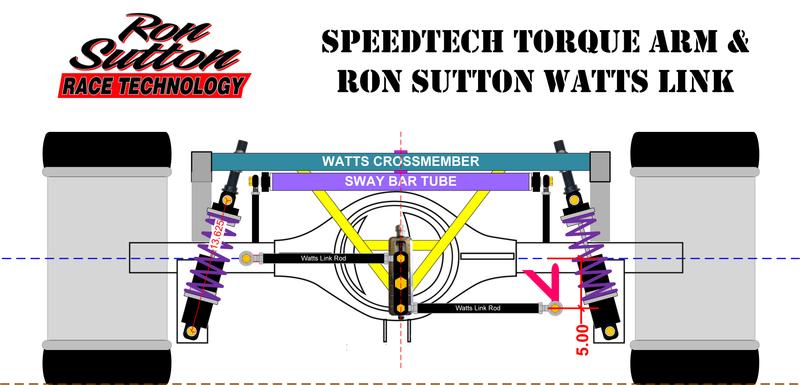

Watt's link: The RRC is located horizontally & vertically at the center of the bell crank pivot that is attached to the rear end housing, either directly or with links. No matter where you mount it or where you adjust it, the RRC is at the center of the bell crank pivot. Angles & the height of the links are important to range, but do not affect the handling.

You need to mount the Watts Bell Crank centered in the chassis to make sure the RRC is centered in the chassis. For some reason, many Racers think the "proper" location for the Watts link is to have both links level. Not sure why that is. We do that when we're building the race car, only to ensure both links are parallel to each other.

I have two versions. One utilizes a 7.5" bell crank. It works perfectly with our combination rear axle mounts that attach the Watts lower link & the coil over shocks 7.5" below the Rear Axle Centerline. (See below) With most of 315-335 tires we run, that places the RRC around 8-1/2" to start with level links. Then if we adjust 2" either way the links don't get into too funky of angles.

But frankly, these days the fastest road course setups are on stiff rate rear springs (550# to 800#) & run the RRC quite low ... typically 7.5" to 9.5" ... so with this 7.5" bell crank version, we're only going up or down about 1". You can read more about this is the Forum Thread about increasing grip.

You'll notice on the illustration above, we have braces going from the bottom of the Ford SVO housing angling to the bottom of our combination axle brackets. We didn't use to do that. But with our fastest Warriors with serious rear downforce, we saw the passenger side bracket bow out from an off track excursion. The spring & watts do not create enough force to bow it. But add in 1200# of downforce & rough excursions & it did. So now we add these 1.25" OD x .065" 4130 braces to eliminate that possibility.

This video shows how our Watts works in action:

I also have a 5" Bell Crank (shown below) that I use for applications that need the roll center higher. With the same 315-335 tires, the RRC is 10" with the links level. That is a good starting point for autocross & other applications that run softer rear springs.

You'll notice it has its own axle mount inward from the shocks. For this version to fit, it needs to go inside the shocks, whereas are 7.5" aligns with he lower shock bolts.

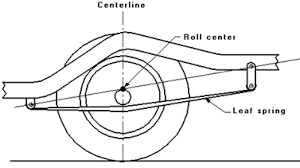

Leaf Springs: The RRC is located horizontally in the center ... halfway between the two sets of leaf springs. Many leaf spring suspension expert sources say the RRC is located vertically at the height equal to the mating line where the leaf spring connects to the housing spring pads. If lowering blocks are utilized, the RC height is in the center of the lowering blocks. In my racing experience, I have not found this to be accurate.

I find the RRC to be higher than that. Other leaf spring suspension expert sources have said to run an imaginary line (datum line) through the front spring pivot bolt to the rear frame hole where the upper shackle bolt goes ... then find the RACL along that line. When I run my calculations like that, the track performance matches.

That's how you calculate your non-adjustable RRC with leaf springs ... UNLESS ... you add a panhard bar or watts link to your leaf spring suspension. I am a big fan of adding a Watts link for Leaf Springs to have an adjustable rear roll center. To do so optimally, you should also add monoball bushings in the leaf spring front & rear, as well as some version of a roller bushing in the top shackle mount. More detail was covered on this earlier this rear suspension thread.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Optimizing the Rear Roll Centers:

If you are racing to win, someone on the crew absolutely needs to master suspension tuning. Period. No exceptions. If you're not dialing your race car in to produce the best driving, balanced handling, fastest lap times ... your competitors are. Rear Roll Center tuning (with straight axle race cars) will be one of the most common tuning tools you utilize.

Track day guys & autocrossers don't have to become a tuner to have fun with your cars. You can buy & install an upgraded aftermarket suspension package that have a "much better than factory" set-up for your car & go run it as is. The car will handle well, outperform most factory cars and be a lot of fun. Just don't disillusion yourself into thinking you're going to show up at serious competitions & beat the "thinkers & tuners" with a bolt on package.

I have found many track day guys & autocrossers say, "I just want to have fun." But for the life of me I don't see how driving an ill-handling car is fun. Nor do I see them happy when all their "buddies" are smoking them on track. I just have a different point of view & a passion for winning. You be you.

It is more fun at the track when your car handles well, is easier (and safer) to drive fast & you're at least as fast as your buddies, if not smoking them on track. That is fun. And the good news is you do NOT need master suspension tuning. You need to know what the tire temps are telling you to tune on & make the handful of tuning changes that are quick & easy to do on your car. If your car is not quick & easy to tune, you loveed up.

If you learn NOTHING else about suspension tuning, learn how the Rear Roll Center affects the balance of handling in your car.

Many track guys & autocrossers aren't tuning on their RRC to balance the car's handling. They find tuning with the RRC tedious and/or confusing ... and therefore they don't do it. They're just suffering through a car that pushes the front tires or is losing rear grip & stepping out.

Tuning the Rear Roll Center with a Straight Axle:

This section is going to be short. Very short. Because tuning the Rear Roll Center is easy to understand & easy to do if you set it up for quick tuning. In the Forum on Track Tuning, I go into this much deeper. But here I'm keeping it simple.

• With Watts or PHB, you simply adjust the rear roll center up for more front grip, or down for more rear grip. 90% of the time it is that simple.

• The exception to this rule is on very fast sweepers in cars with no or low rear aero downforce, if the car is rolling too much & scary loose, you'll want to raise the RRC for more rear grip.

• Only with a PHB, if you need more rear grip on left hand corners, adjust the driver side lower. If you need more rear grip on right hand corners, adjust the passenger side lower. If you need more front grip on left hand corners, adjust the driver side higher. If you need more front grip on right hand corners, adjust the passenger side higher. Combinations of these also work well.

I will go more in-depth & explain the whys in the tuning forum thread.

#54

Rear Suspension & Geometry for Track & Racing / Re: Rear Suspension & Geometry...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Dec 22, 2025, 11:59 AMDouble Wishbone Independent Rear Suspensions

I have a love/hate relationship with IRS. My aversion for Independent Rear Suspensions is based on they're heavy & not easily Anti-Squat or Rear Roll Center adjustable. We can't offset anything to eliminate Torque Steer, nor can we Decouple them in any way. So, we deal with a compromise Anti-Squat on corner entry & exit. I am a "Tuner." I love to dial in the total suspension at the track to be perfectly optimum ... in other words ... faster than all our competitors. IRS puts me in a box with less tuning tools at the track. A few different ones, but nothing that allows me to dial in Anti-Squat or Rear Roll Center.

My love for IRS is based on the infinite range of roll steer & dynamic toe adjustability. We can make each side steer in or out to our heart's content. If you're not familiar, low to zero ride height rule race cars, struggle to turn well due to little or no pitch angle change. In other words, if the ride height starts at 1/4", we're obviously not high travel diving the front end.

That lack of pitch change, CG migration & load transfer make it harder for these cars to turn well in tight corners. The solution & savior is IRS, because we can dial in Rear Roll Steer. With that, the rear of the car is helping the front of the car turn better. In my racing experience, cars with 2" & higher static ride heights don't "need" IRS. They can benefit from IRS if the front suspension is not up to par. But an offset, decoupled 3-Link will provide greater grip on entry & exit than any IRS.

More love for IRS is based on the fact that ... well ... each side is independent. We can obviously keep the tires better loaded & following the irregularities of the track than a straight axle. The smoother the track, the less advantage this is. The rougher the track, the more of an advantage this is. Lastly, if we are running a rear engine configuration, IRS is our only choice. In this thread, I dive deeper into IRS setups & I'll show you why I love the Multi-Link IRS a little bit more than conventional control arm IRS.

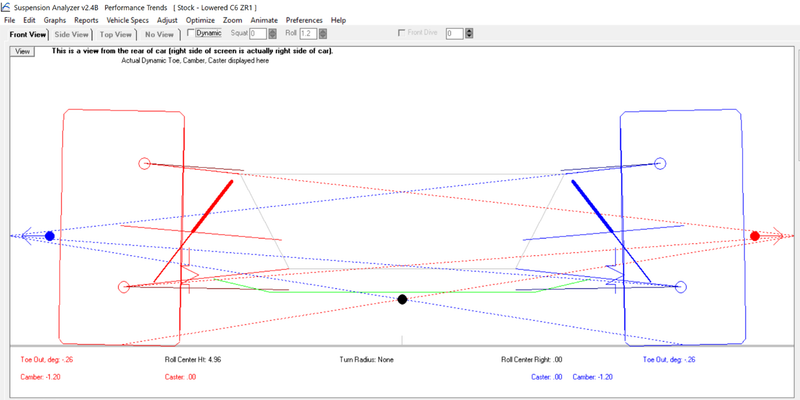

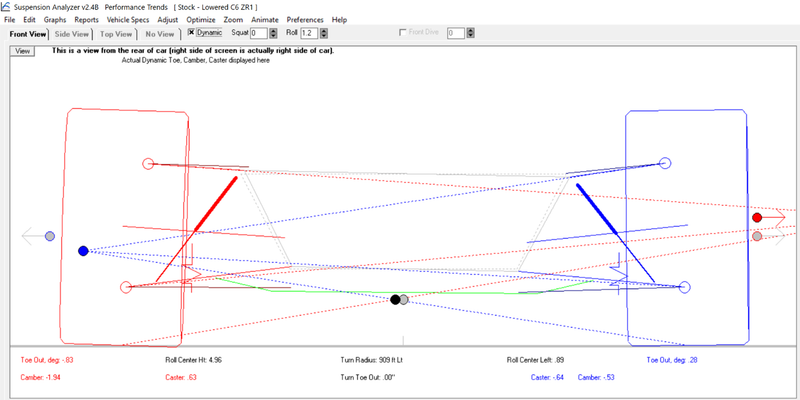

First, let's start with the typical double wishbone IRS that utilizes unequal length control arms. In racing IRS designs, we can build the control arms any shape & size that will fit. Some Racers like to (or need to) utilize OEM control arms or copies of. Most OEM IRS control arms are unequal length to achieve goals they have for the production cars driven on the street. We don't have those concerns, but for this first example, we are utilizing C6 Corvette upper & lower control arms.

C6 Z06 Lowered Independent Rear Suspensions

First, let's start with the typical double wishbone IRS that utilizes unequal length control arms. In racing IRS designs, we can build the control arms any shape & size that will fit. Some Racers like to (or need to) utilize OEM control arms or copies of. Most OEM IRS control arms are unequal length to achieve goals they have for the production cars driven on the street. We don't have those concerns, but for this first example, we are utilizing C6 Corvette upper & lower control arms.

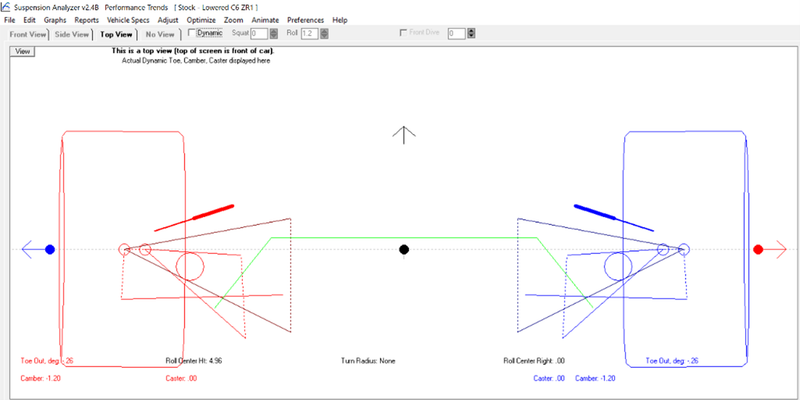

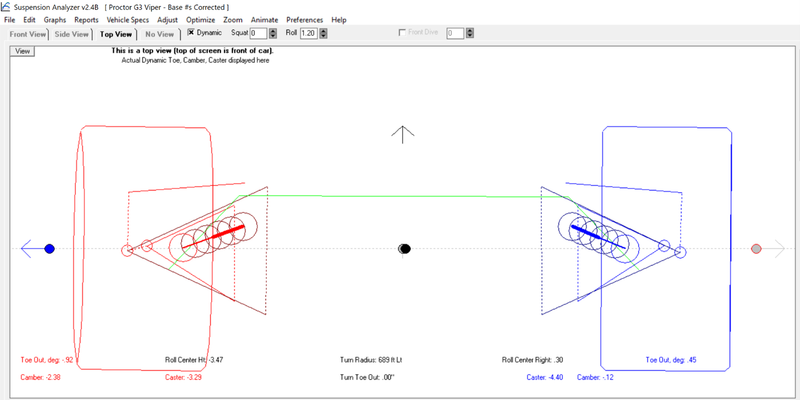

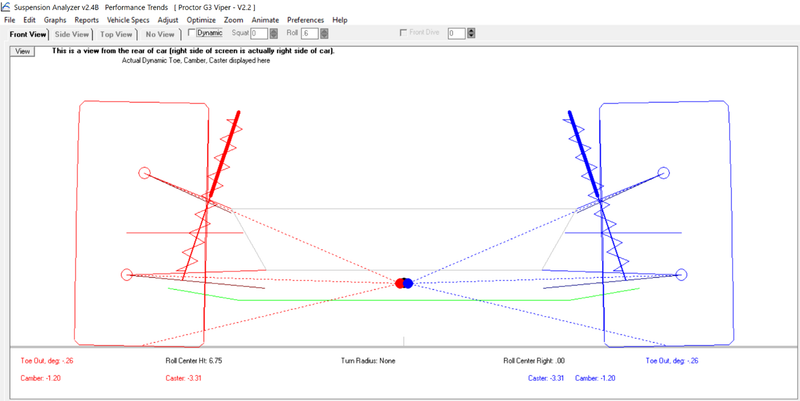

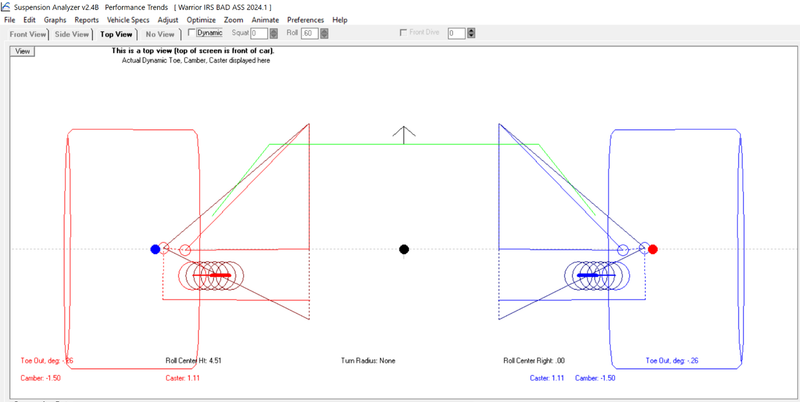

If you look closely at the toe numbers, you can see the static rear toe-in (-.26° = 1/16" toe-in each side = 1/8" total toe-in) changes from a -.26 to positive .25 ... meaning the outside rear tire goes from 1/16" toe-in to 1/16" toe out. The inside rear tire goes from -1/16" toe-in to 3/16" toe-in. That means the rear tires went into positive rear steer with both tires steering towards the outside of the corner. You can also see we lose a lot of our negative camber. We started with -1.2° & lost about .7° of that with body roll.

This is fine ... If you have enough rear wing to keep the rear tires gripped up. In fact, this is common. The rear steer helps the car turn better in tight corners (where air speed is low & the wing is less effective). Then at higher speeds, when the rear steer would make the car loose, the wing saves our ass.

Both of these issues are geometry problems that can be fixed. The camber change is a control arm geometry issue & the rear roll steer is a toe-link geometry issue. All of this is fixable if it benefits your race car goals.

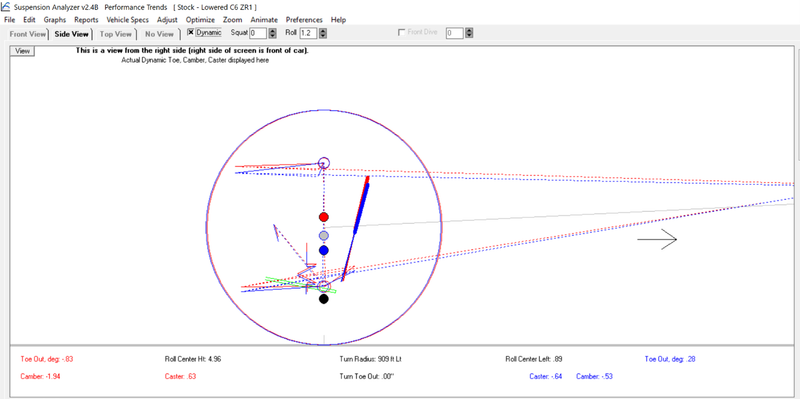

Below is a side view of the stock, but lowered C6 Z06 suspension. It doesn't show this, but how the lines from the control arms intersect produces a 59" swing arm length & 45% Anti-Squat. Both great for road courses. If we ONLY autocrossed this car, it would benefit from 10-15% more Anti-Squat.

Top view below. Nothing out of the ordinary. Easy to see the "unequal length" control arms.

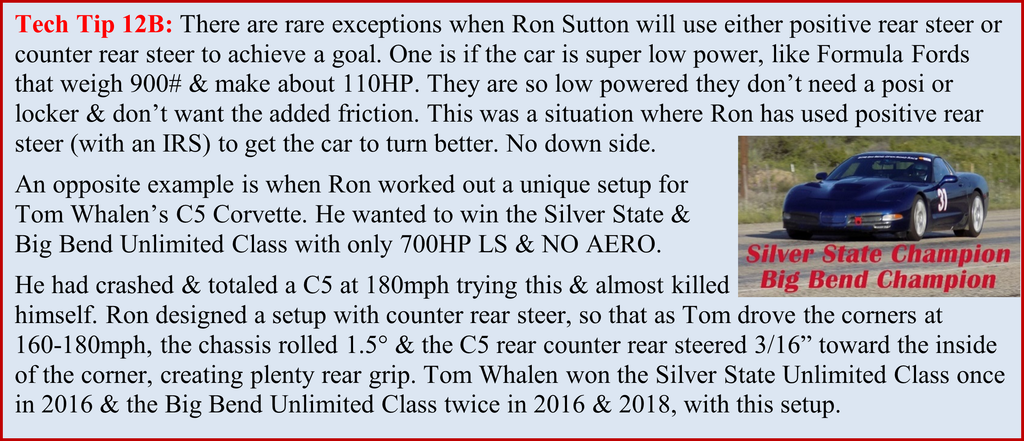

A quick word on counter roll steer. We practically never run counter roll steer. Frankly, we practically never run positive roll steer either. If the front suspension is really good, it doesn't need any help turning from the rear with positive steer. What about counter roll steer? If you have plenty rear grip (both mechanical & aero), you do not need more rear grip from counter rear steer. There was ONE TIME I designed a C5 rear IRS with counter roll steer.

Stock Lowered Viper Independent Rear Suspensions

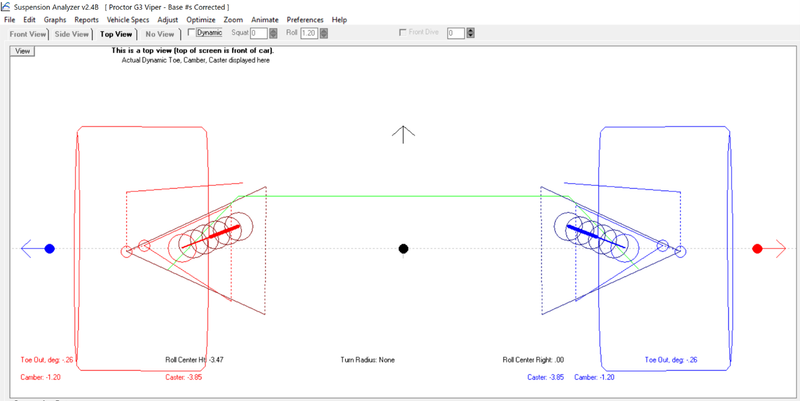

For years I had heard the handling in Dodge Vipers were "evil." I love the style & thought about buying one for fun. I had a client that was track & competing in his Gen 3 Viper he brought to us to improve. We started by measuring all the suspension & steering geometry points. After I entered all the data & looked at the geometry, I just knew the crew had made some measurement errors. So, I had a different guy remeasure. Nope ... the original dimensions were correct.

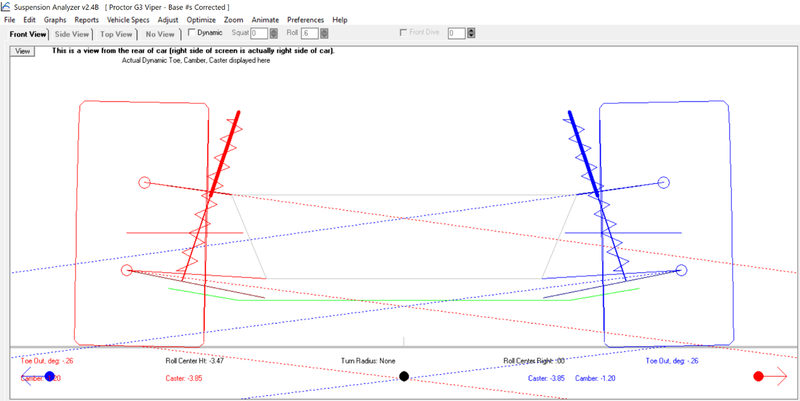

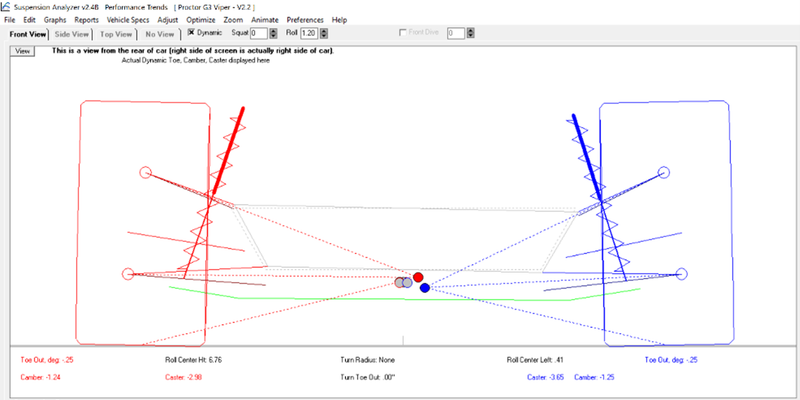

When you look at the top view (above), things look pretty normal. It's when I looked at the rear view (below) ... that I agreed it's true ... these Vipers ARE trying to kill the Drivers. Holy cow! I'd never seen a car with the Rear Roll Center UNDER the ground level!

When you look at the image above & below, the upper image is static & the lower image is dynamic with body roll in the corner. The RRC below ground makes the Roll Axis backwards ... makes the rear of the car roll over more than the front (crazy) ... and the icing on the cake ... is the roll steer is positive (meaning the rear wheels turn towards the outside of the corner) ... AND the camber loss was huge! Had to be scary to drive at the limit.

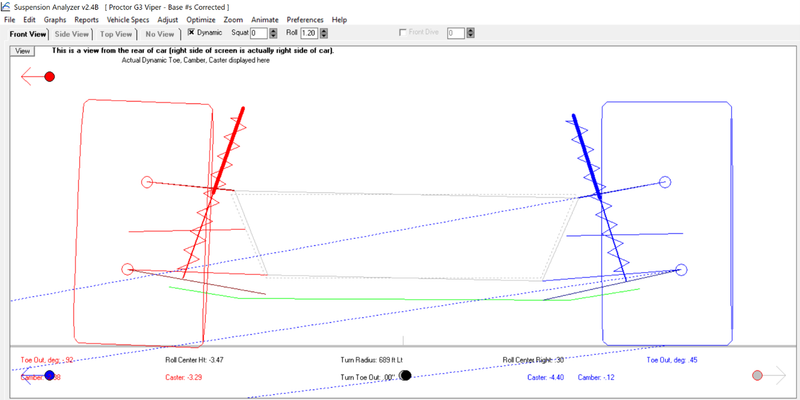

He asked us to fix it, which we did. It required buying new control arm buckets from Dodge & remounting 6 of them ... two to improve the front ... and 4 to fix the rear. After we relocated the IRS control arm mounting points, the rear view of the Viper looked like the images you see below.

When you look at the images above, the upper image is static & the lower image is dynamic with body roll in the corner. You can see, simply by relocating the control arm mounts, the same control arms & uprights produce a very drivable combination.

You can see the RRC is 6-3/4" ... to mate up with his 0" ground level FRC ... and create a normal Roll Axis (Pitch down in front). Dynamically you can see rear camber (-1.2°) & rear toe-in (.26° = 1/16" toe-in each side = 1/8" total toe-in) change VERY LITTLE with the 1.2° rear body roll.

Track-Warrior Independent Rear Suspension

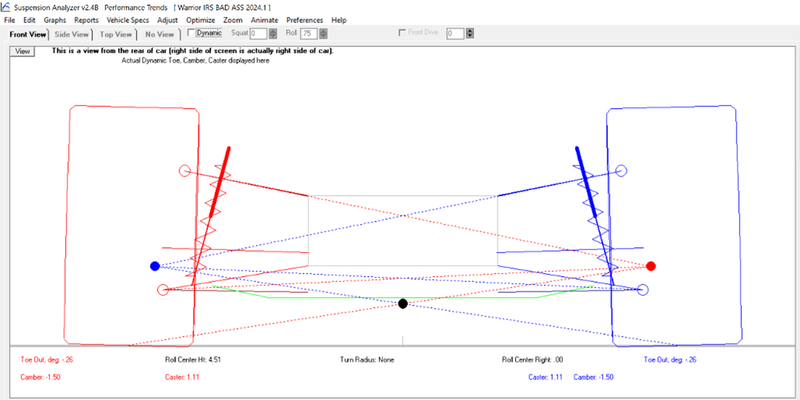

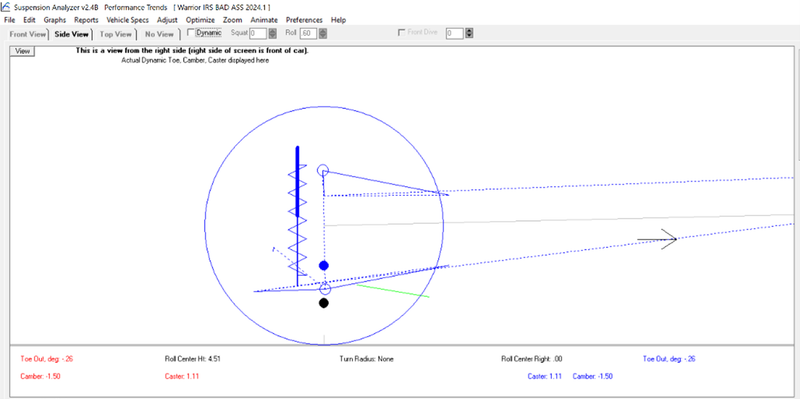

For my Warrior line of Tube Chassis cars, I make two very different versions of IRS. For the Track-Warrior, we utilize an (almost) equal length control arm IRS. And for the Race-Warrior, we utilize a Multi-Link IRS. The Track-Warrior version is simpler, less cost & very effective. The Race-Warrior version is more complex, more expensive, but can be configured to achieve damn near any geometry & final result with tire camber, toe & steer we can dream up. Here is the Track-Warrior ...

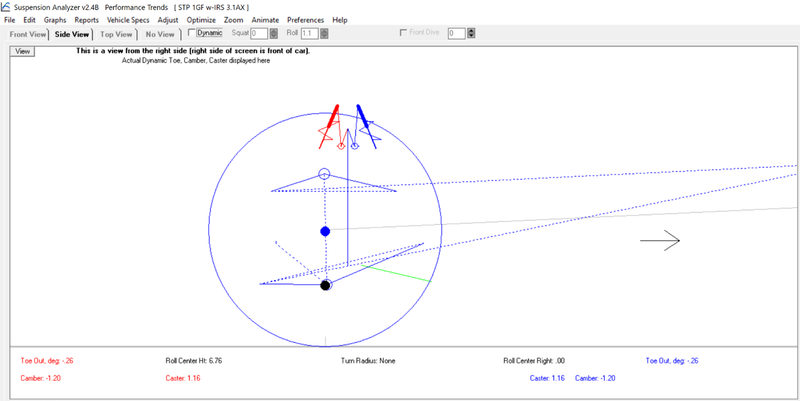

You'll notice this one is configured for a 4.5" RRC. That works well for high powered, fast track cars as long as the front suspension is doing its job. This low of an RRC does require a wing, but a modest one with 600-800# of downforce at 150mph is plenty.

The image below is dynamic, with 0.6° roll angle. (Without a wing, the roll angle would be higher.) You can see the camber change is about 0.3° on each side. In my racing experience I have found around 1.2° dynamic camber works pretty well on most 30 series sidewall race tires on 18" wheels for track cars. We run higher negative camber on our Race-Warrior stuff, because the corner speeds & g-forces are both significantly higher.

If you compare both images above, the static & dynamic, you'll notice there is no rear roll steer. The 1/16" of toe in on each side stays intact during body roll. That is a function of the toe-link geometry. I like to make my stuff with easily adjustable (and fine tunable) toe-links on the chassis end & at the upright. That way you can really dial in zero roll steer, positive or counter roll steer. (*Some Racers say "negative roll steer" in place of "counter roll steer".)

It doesn't show in the image below, but the swing arm is 56.8" & the Anti-Squat is 47.7%.

If you looked at the rear view thoroughly, you could tell the control arms were almost equal length. Since this IRS is for a tube chassis Track-Warrior, it's easy to design a frame with mounts the same width top & bottom. You can see this easily looking from the top view (image below).

The actual UCA & LCA length difference is 2" due to KPI of this spindle & the designed in negative camber. But that difference is much smaller than most designs. It makes it easier to achieve minimal camber change during roll.

Speedtech Independent Rear Suspension

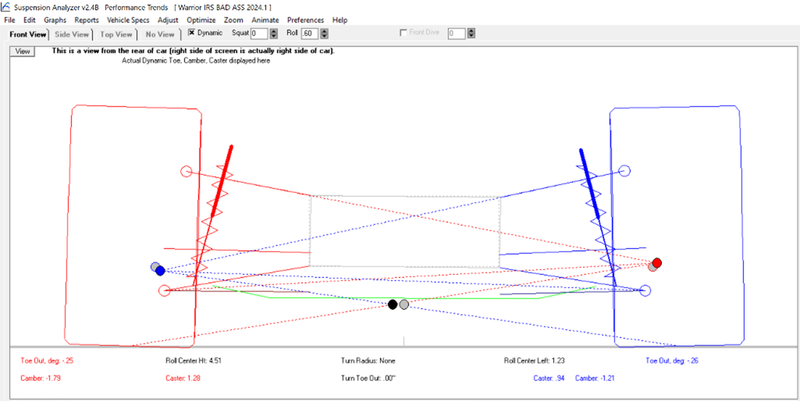

When I was hired to design the Speedtech Independent Suspension, the original goal was to make two front mounting holes for the lower control arm. One that produced a setup optimum for autocross & the other for road courses. The autocross geometry is shown below.

This setup above was optimized for autocross with a 6-3/4" rear roll center, 59" swing arm & 70%+ Anti-Squat.

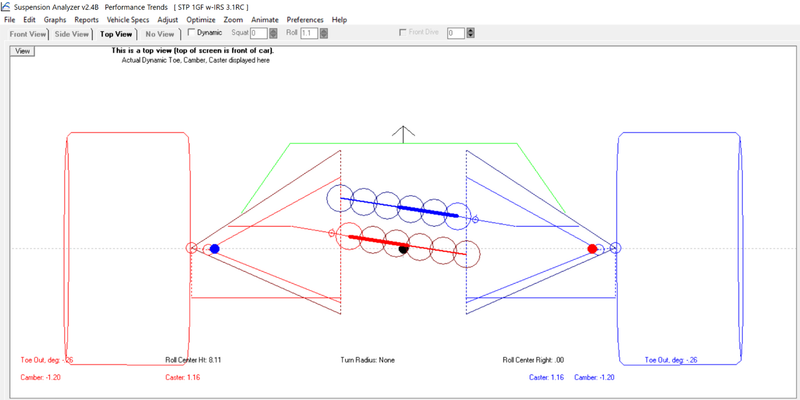

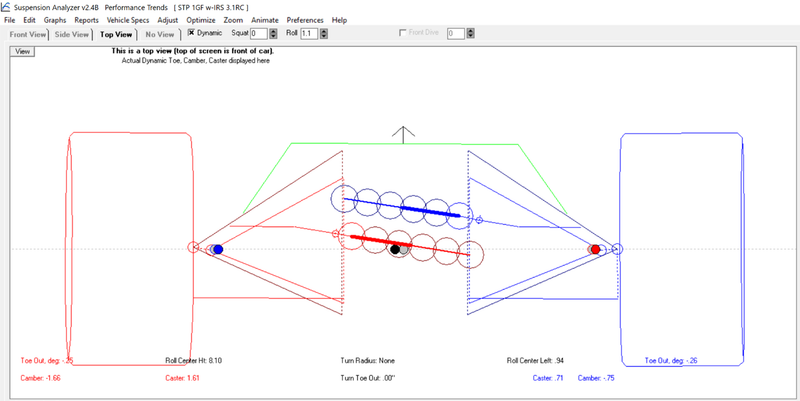

The image above shows the top view of the road course setup. You'll notice this IRS has the same almost equal length control arms to minimize camber & geometry change during body roll. This setup was optimized for road courses with a 8.11" rear roll center, 76-3/4" swing arm & 50%+ Anti-Squat.

This IRS also features tunable toe links on both ends, to fine tune any desired roll steer. The baseline is zero roll steer, but you can dial in counter roll steer for road courses, if you don't have enough rear aero downforce. And of course, you can dial in positive roll steer to help the car turn on tight road courses & autocross tracks. You can see from the two images above, even with 1.1° body roll, the rear tires are still straight & toed in 1/16" on each side.

#55

Rear Suspension & Geometry for Track & Racing / Re: Rear Suspension & Geometry...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Dec 10, 2025, 02:22 PMTorque Distribution in Straight Axle Rear Suspensions

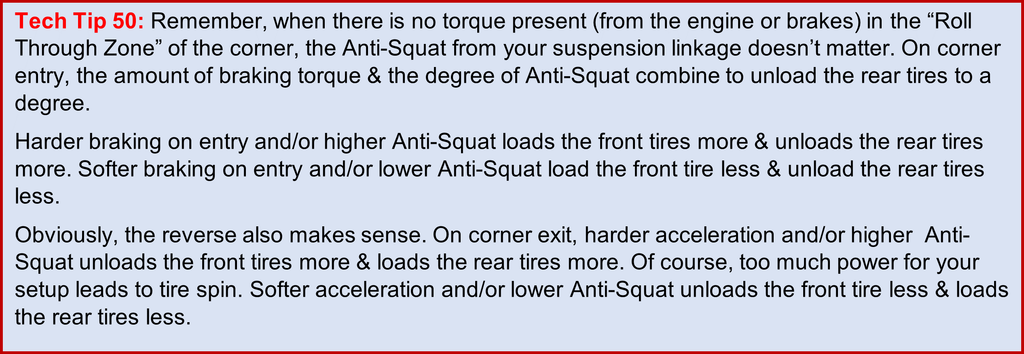

I learned a long time ago to treat Anti-Squat percentage as small player in the 12 factors in how a rear suspension works. So, a target Anti-Squat percentage is never my only goal for rear traction under acceleration. That throws most people off, as they have been taught forever to focus on Anti-Squat exclusively for forward bite (rear grip under acceleration). Believe it or not, "resultant thrust angle" & pick up point are more important.

Resultant thrust angle is the direction the rear suspension is pushing the chassis. It is always some percentage up (lift) and some percentage forward. The Anti-Squat percentage matters ... but it's just a byproduct of getting the desired resultant thrust angle ... not the priority.

A key thing to understand in all linkage type rear suspensions is they work WITH the forces from the rear axle. Under engine power, there is torque (force) coming through the driveshaft, ring, pinion & axles to accelerate the rotation of the rear tires. Under braking, there is torque (force) coming through the axle tubes (assuming the rear calipers are bolted to the axle tube) to slow the rotation of the rear tires.

Sir Isaac Newton's famous quote for his Third Law of Motion is: "To every action there is always opposed an equal reaction; or the mutual actions of two bodies upon each other are always equal, and directed to contrary parts," which is commonly summarized as, "For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction". This principle explains that forces always occur in pairs, acting on different objects, like a rocket pushing gas backward (action) and the gas pushing the rocket forward (reaction)

With this knowledge, we know along with the torque (force) coming through the driveshaft, ring, pinion & axles to rotate the rear tires one direction, there is equal & opposite torque (force) to rotate the axle housing the opposite direction. This is why the front of the pinion picks up during acceleration.

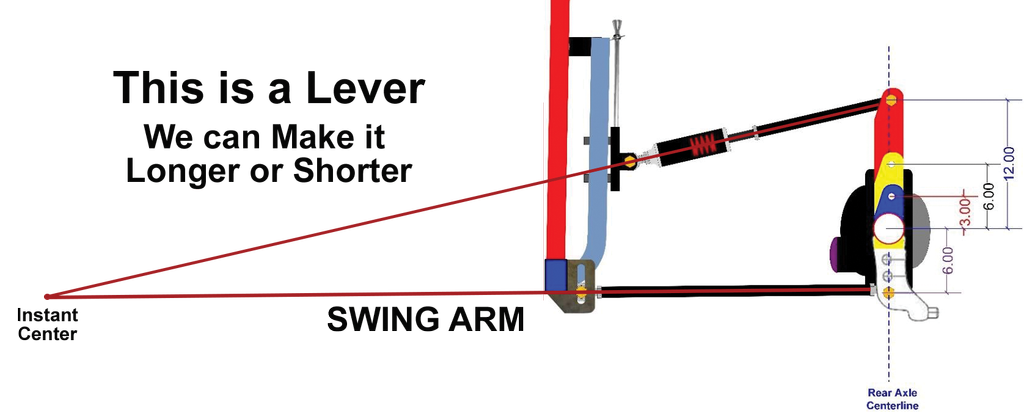

This force to rotate the housing IS THE FORCE we're using to make the linkage style suspension do work. The linkage suspension is SIMPLY A LEVER. Make sense? If not, re-read the section above.

Looking at the image above, you know the tires need to rotate counter clockwise to move the car forward. The equal & opposite reaction is the rear axle housing will have equal force trying to rotate it the opposite way ... clockwise ... from this Drivers side view. Of course, the rear axle housing doesn't "freely rotate" because it is attached to the chassis some way.

For this discussion of linkage type rear suspensions. It is the 3-Link, 4-Link, Torque Arm etc., that is prevented the rear axle housing from freely rotating. Again, the 3-Link, 4-Link, Torque Arm etc. is the lever & the equal & opposite reaction from the engine torque is our force. Force x Leverage = Work.

The "work" we're doing is utilizing the force, with a lever, to load the rear tires with more than just the rear weight of the car. We use this force, with a lever (the Torque Arm in this case) to LIFT on the chassis. The amount lift force is proportionately the load force ADDED to the rear tires for increased grip. Yes ... added. The rear tires already have load on them from the rear weight of the race car. Upon hard acceleration, the Torque Arm in this case is lifting on the chassis & placing additional load on the rear tires to increase rear grip.

If you think about a drag car doing a wheelie on the launch, it's clear they're using their force & their lever to pick up the entire weight of the car to load the rear tires. We're not going quite that far, but the principle is the same.

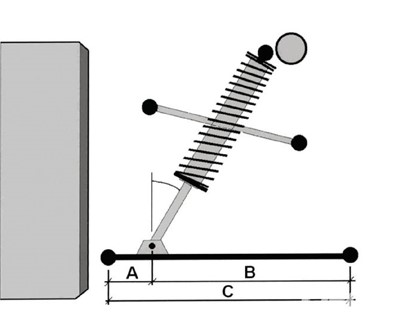

With 3-Link & 4-Link "Levers" we can adjust the length of the Swing Arm (which is defined as the distance from the RACL to the IC). This is super important to track tuning.

All rear end linkage tuning is based around 3 simple strategies:

1. Where are we lifting

2. How much housing torque is distributed to lifting the car?

3. How much housing torque is distributed to pushing the car forward?

1. Where you're lifting is normally the IC in most suspensions, except in a torque arm, where it is the pick up point. More on this later.

• The shorter you make the Swing Arm, the quicker & harder it will load the tires, but with less weight & for a shorter period.

• The longer the Swing Arm, the slower & softer it will load the tires, but with more weight & for a longer period.

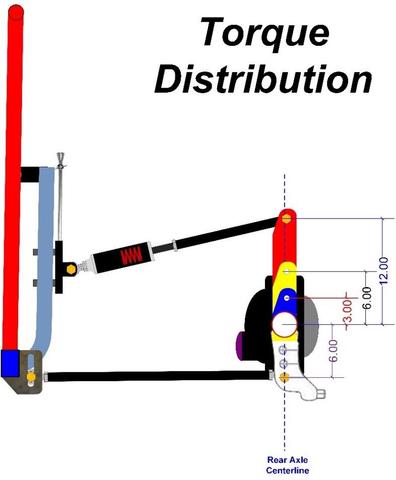

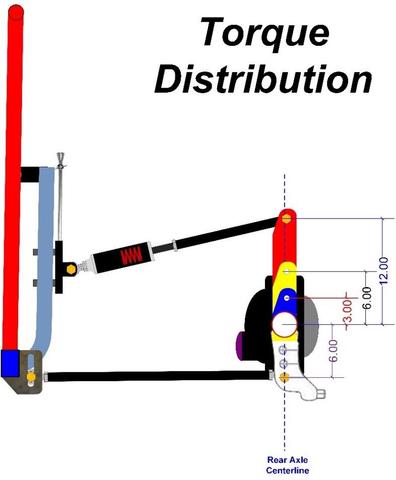

2 & 3. The location & angle of the links ... and location of the link pivots ... define how much of the housing torque is distributed to lifting the car & how much is distributed to pushing the car forward. You can not change one without affecting the other.

• More torque distributed to lift ... plants the tires quicker & harder ... leaving less torque to push the car forward.

• Less torque distributed to lift ... plants the tires slower & softer ... leaving more torque to push the car forward.

These sound similar, but 1 is different from 2 & 3. Where you lift does not necessarily define torque distribution. It does define how much weight of the car can be used to load the tires. This can be a little cloudy, but I think it will be clear & simple when you see how to tune it with a 3 or 4 link. With high powered road race cars, I usually set the IC under the CG as a starting point ... so I have the full weight of the car to load the tires ... then I work out the torque optimum distribution from the housing for chassis lift & forward push. Here is how to set it up ...

More lift/less forward push > Increase Rear Tire Loading, Grip & Violence:

A. Increase distance of top link housing mount pivot ABOVE the RACL

B. Increase distance of top link housing mount pivot BEHIND the RACL

C. Decrease distance of lower link housing mount pivot BELOW the RACL

D. Increase distance of lower link housing mount pivot in BEHIND of the RACL

E. Increase the distance of the lower link chassis mount pivot in front of the RACL compared to top link chassis mount pivot in front of the axle housing CL

F. Increase downward angle of top links (going forward from RACL)

G. Increase upward angle of lower links (going forward from RACL)

A, B, D & E: Can be achieved without affecting the IC arm lift point, if built into the design.

C: Has a minor shortening effect on the IC arm lift point & raising the IC.

F: Shortens the IC arm lift point significantly ... and has no impact on rear steer.

G: Shortens the IC arm lift point significantly ... BUT adds positive rear steer. Only do this if positive rear steer effect is desired too.

Less lift/more forward push > Decrease Rear Tire Loading, Grip & Violence:

H. Decrease distance of top link housing mount pivot ABOVE the RACL

I. Decrease distance of top link housing mount pivot BEHIND the RACL

J. Increase distance of lower link housing mount pivot BELOW the RACL

K. Decrease distance of lower link housing mount pivot in BEHIND of the RACL

L. Decrease the distance of the lower link chassis mount pivot in front of the RACL compared to top link chassis mount pivot in front of the axle housing CL

M. Decrease downward angle of top links (going forward from RACL)

N. Decrease upward angle of lower links (going forward from RACL) or angle downward

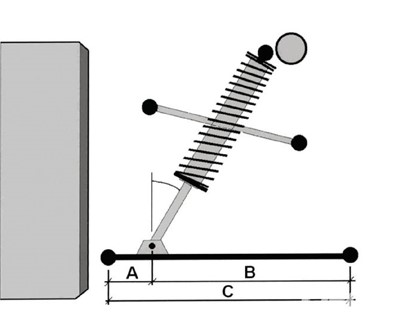

Let's do some math to help make this clearer. Look at the diagram below & notice the dimensions of axle housing link mounts. For discussion sake only, I'm keeping the lower link mount pivot 6" below the RACL.

• If we make the top link 3" above RACL we would have 9" between the lower & top link pivot mounts. That means the 3" top link mount would utilize 1/3 of the axle force lifting on the car & 6" lower link mount would utilize 2/3 of the force pushing the car forward.

• If we make the top link 6" above RACL we would have 12" between the lower & top link pivot mounts. That means the 6" top link mount would utilize 1/2 of the axle force lifting on the car & 6" lower link mount would utilize 1/2 of the force pushing the car forward.

• If we make the top link 12" above RACL we would have 18" between the lower & top link pivot mounts. That means the 12" top link mount would utilize 2/3 of the axle force lifting on the car & 6" lower link mount would utilize 1/3 of the force pushing the car forward.

I tune on this lift/forward push balance ... with the IC arm pick up point starting under the CG.

• If I run out off lift adjustment range ... and still need more lift for this application ... that's telling me I need a shorter IC arm pick up point.

• If I run out off forward push adjustment range ... and still need more forward push for this application ... that's telling me I need a longer IC arm pick up point.

• Like all tuning, we're looking for the best compromise for each individual application.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

CRITICAL Guidelines for torque distribution:

• When you have more engine torque to rotate the housing, you need less torque directed to lifting & more going to push/drive the car forward.

• When you have less engine torque to rotate the housing, you need more of that torque directed to lifting & less pushing the car forward.

• When you have taller, softer sidewall tires ... like drag slicks, or even stock car tires ... you need less torque directed to lifting & more going to push/drive the car forward.

• When you have shorter, stiffer sidewall tires, you need more of that torque directed to lifting & less pushing the car forward.

Engine power output, curve, tire design, track conditions, etc ... all play a role in defining the optimum setup any given day at the track. The key is finding the optimum balance for each individual application.

Torque Arm:

With a torque arm, you can not do A, C, F, H, I or M ... because the torque arm, being solid mounted to the housing, is based at the RACL. But you can do the others. Personally, I stay away from G & N, due to rear steer, unless that is what I need also. So other than torque arm pick up point length, your tuning tools with a torque arm are primarily C, D, J & K ... the distance & relation the lower link pivot mount are from the RACL. Plus E & L which is the distance of the chassis mount pivots.

If you moved the lower links all the way up level with the axle CL ... and the lower links were the same length as the torque arm ... you would have 50/50 torque distribution of lift & push.

50/50 is the highest lift torque distribution you can achieve with a torque arm.

• If you place the lower links down below the RACL you are shifting torque distribution to decrease lift & increase forward push.

• If you make the lower links shorter than the torque arm, you are shifting torque distribution to decrease lift & increase forward push.

• So, most torque arm designs distribute the housing torque for less lift and more push.

• Unfortunately, torque arm designs don't offer as much adjustability for this.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

There are several varying theories & methods on determining the IC of a torque arm suspension.

Let's cover those first, then I'll share what we learned from testing.

1. Some folks believe the IC is where the line of the lower links converge with the line from the axle through the torque arm pick up point.

2. Some folks believe the IC is where the front point of the torque arm lifts up on the chassis and the lower links only affect roll steer.

3. Some folks believe the IC is where the line of the lower links cross an imaginary vertical line at the torque arm pick up point.

------------------------------------------------------------------

Now I'll throw you a curve ball. I have found none of these three are completely correct and all three are partially correct. Huh? I know. Stay with me.

I have zero drag race experience with a torque arm suspension. My 10 years of drag racing were with ladder bars initially, then 4-Links. All of my experience with tuning, testing & racing the torque arm suspension are in road racing. This is a mental reach at first, the torque arm suspension is rare in that its lift point and IC are not necessarily the same. WTH?

I know. Be patient with me and I'll make it all make sense & come together clearly. Here goes ...

A torque arm applies lifting force at the pick up point. Period. This point is not affected by the lower links. The lower links angle or height, do not change where the torque arm is applying its lifting force. Nothing stops the torque arm from lifting at its pick up point. Nothing changes where the torque arm is lifting from its pick up point. If you embrace that, the rest will make sense.

The lower links still help define the instant center that forms the swing arm & arc the housing rotates on. The lower links angle & height ... and the line projecting through them ... converge with the line from the axle through the torque arm pick up point ... to form an instant center. This defines the "Swing Arm" characteristics of the rear suspension. This is the arc the suspension pivots & rotates on. But it does not change where the lifting force is. The lifting force is still at the pick up point of the torque arm.

This is what is rare. And this is what confuses most folks. We are all used to the IC being the point where the lifting force is. With a torque arm, it is not, because it is attached solidly to the housing like a ladder bar.

We can change how the torque arm suspension works and how it loads the tires by moving the lower links. We can affect the torque distribution of lift & push ... but we're not changing the point of lifting force. So, what do the lower links affect? A lot! The lower link vertical separation from the axle CL affects the torque loading percentages of the links. Most folks know that under acceleration the lower links push.

The lower links push & drive the car forward. The closer the lower links are to the axle CL the less torque is applied to pushing the car forward. Therefore more torque is transferred through the torque arm to lift. The farther the lower links are from the axle CL the more torque is applied to pushing the car forward. Therefore less torque is transferred through the torque arm to lift.

So, in this way, moving the links higher off the ground & closer to the RACL, moves the IC up, creating a higher Anti-Squat %. And the result is "almost" the same as achieving a higher Anti-Squat % with all other rear suspension models. More force from the housing rotation is applied to lifting & less to pushing. But the torque arm is still applying lifting force at the pick up point. That point does not change with lower link adjustments.

Conversely, moving the links lower to the ground & farther from the RACL, moves the IC down, creating a lower Anti-Squat %. And the result is "almost" the same as achieving a lower Anti-Squat % with all other rear suspension models. Less force from the housing rotation is applied to lifting & more to pushing. But the torque arm is still applying lifting force at the pick up point. That point does not change with lower link adjustments.

Now let's discuss lower link angle. Adjusting the lower link angle so the front is higher than the rear ... or the angle is running uphill going forward as I like to say ... moves the IC up, creating a higher Anti-Squat %. And the result is "almost" the same as achieving a higher Anti-Squat % with all other rear suspension models. More force from the housing rotation is applied to lifting & less to pushing. But the torque arm is still applying lifting force at the same pick up point. That does not change with lower link adjustments. With this adjustment you have created positive rear steer.

Conversely, adjusting the lower link angle so the front is lower than the rear ... or the angle is running downhill going forward ... moves the IC down, creating a lower Anti-Squat %. And the result is "almost" the same as achieving a lower Anti-Squat % with all other rear suspension models. Less force from the housing rotation is applied to lifting & more to pushing. But the torque arm is still applying lifting force at the same pick up point. That does not change with lower link adjustments. With this adjustment you have created negative or counter rear steer.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

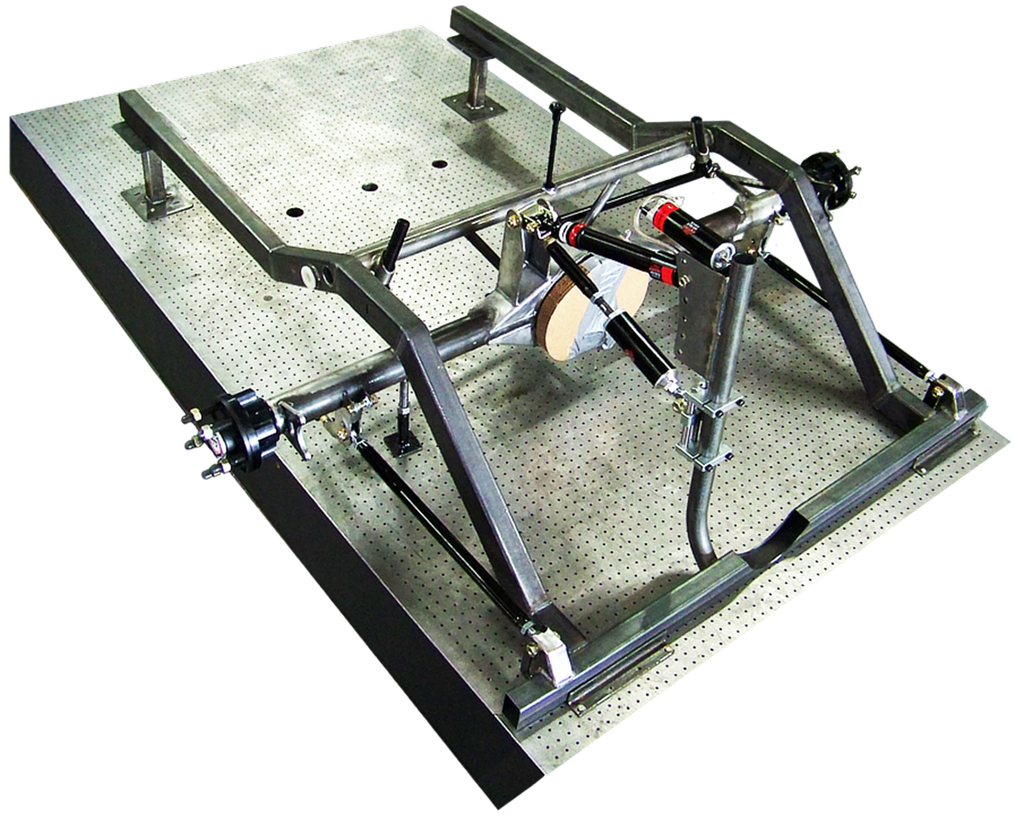

3-Link:

Assuming the 3-Link is designed with the proper range of adjustment holes or Jack Screw Adjuster ... we can make any of the adjustments ... A through N ... with a 3-Link (4-Link too) to achieve the optimum pick up point combined with the optimum lift/push torque distribution.

As outlined above in the math example:

• We can achieve less than 50% lift distribution ... for ultra high powered race & track cars.

• We can achieve 50/50 lift/push torque distribution ... for high powered race & track cars.

• We can achieve greater than 50% lift distribution ... for moderate & lower powered race & track cars.

• We can achieve any lift/push torque distribution ... combined with any swing arm length.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Important Note: Utilizing Torque Absorbers in 3-Links & Decoupled 3-Links allow us to run MUCH MORE "lift" in our rear suspension design with no side effects. We can literally run greater than 50% lift distribution with a HIGH POWERED Race Car for the best of both worlds.

#56

Rear Suspension & Geometry for Track & Racing / Re: Rear Suspension & Geometry...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Dec 10, 2025, 02:03 PMOffset 3-Link Race Suspensions

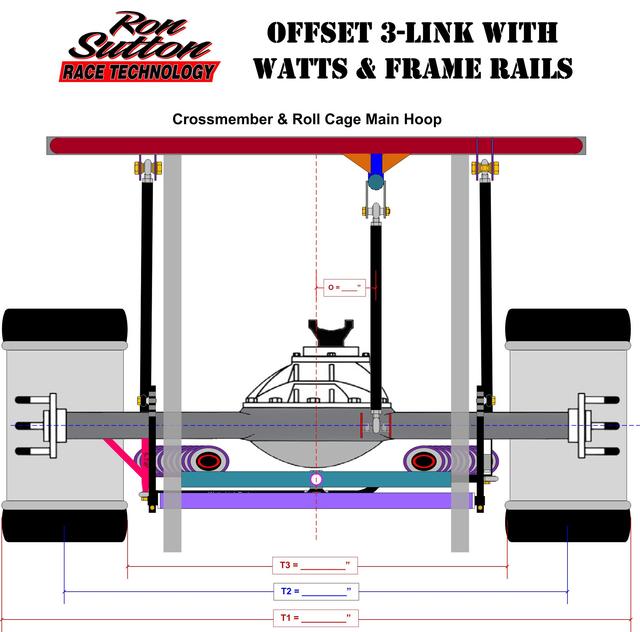

Under load from the driveshaft, the rear end housing wants to rotate the same direction the driveshaft is ... counter clockwise from the rear view, clockwise from a front view. So as torque is applied the left rear tire is loaded more & the right rear tire is loaded less. This makes the car want to "drive" to the right, a small amount, under hard acceleration. As you make left hand turns the car has more "forward bite" during corner exit ... than right hand turns, which have less "forward bite" during corner exit.

The difference isn't huge, but it exists. If it isn't counteracted ... the effect amplifies with increased power output. For 3-Links, the upper link can be offset to the passenger side to help counteract this torque on acceleration. The formulas I've seen other people use involve rear steer, which makes no sense for handling cars.

Very few people can tell you accurately how far to offset it, because it changes with gear ratio & friction within your rear end. A rule of thumb is 8-15% of track width. I have my own proprietary formulas I use, based on my knowledge of where the force comes from & high tech testing of dynamic loads with load cells. This allows me to calculate the amount of force difference from the left rear to right rear tire & offset the top link precisely to zero out any torque steer. I don't share this formula publicly, but I do offer this information to clients running my offset 3-Links.

In many race applications, it makes sense to make the top link mounts wide, so you can adjust the top link side to side to dial in the optimum torque steer cancelatio. Sometimes in the real world, packaging challenges play a role & prevent this.

Offset 3-Links with Torque Absorbers

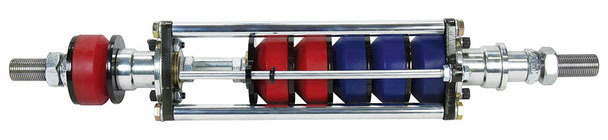

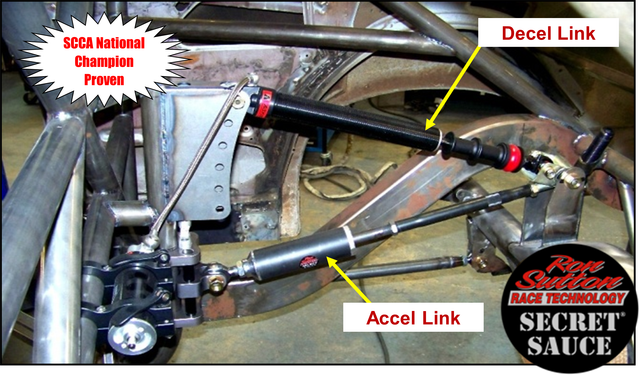

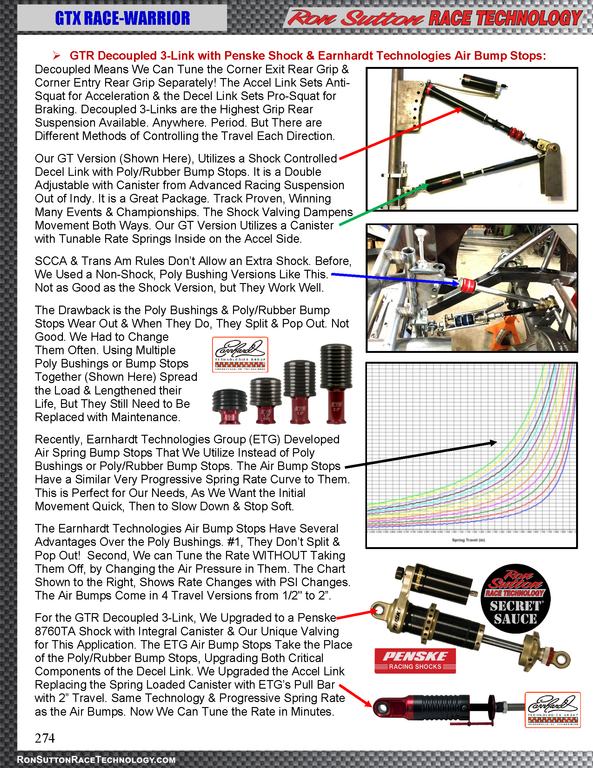

Most tire spin is from the initial "shock" the tire gets when the driver cracks (slams?) the throttle to get out of the corner. Once the tire is spinning, it's hard to get it to stop. You need to lift & roll on the throttle again. Big loss of lap time. Torque Absorbers can be added to 3-Links & Torque Arm rear suspensions. They are usually a poly (polyurethane) or hard rubber Bump Stop that has been tested for spring/load rate.

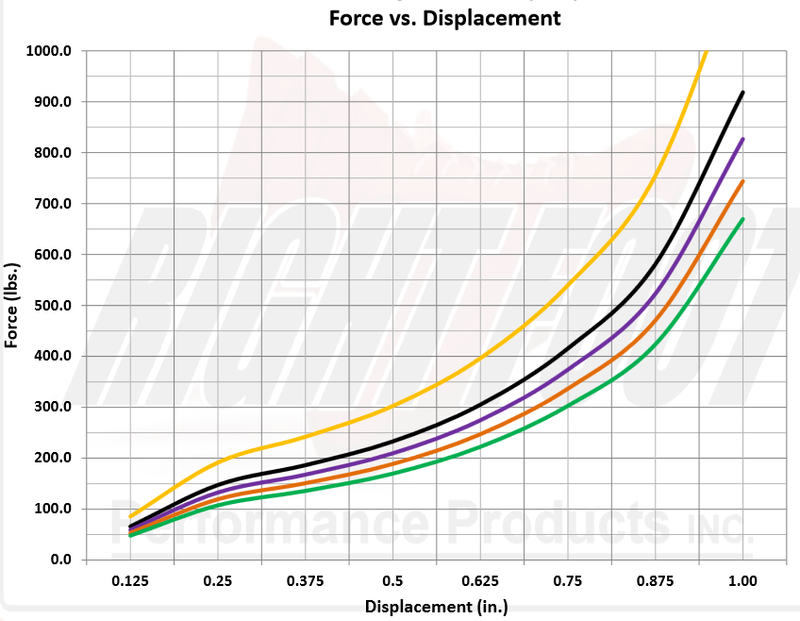

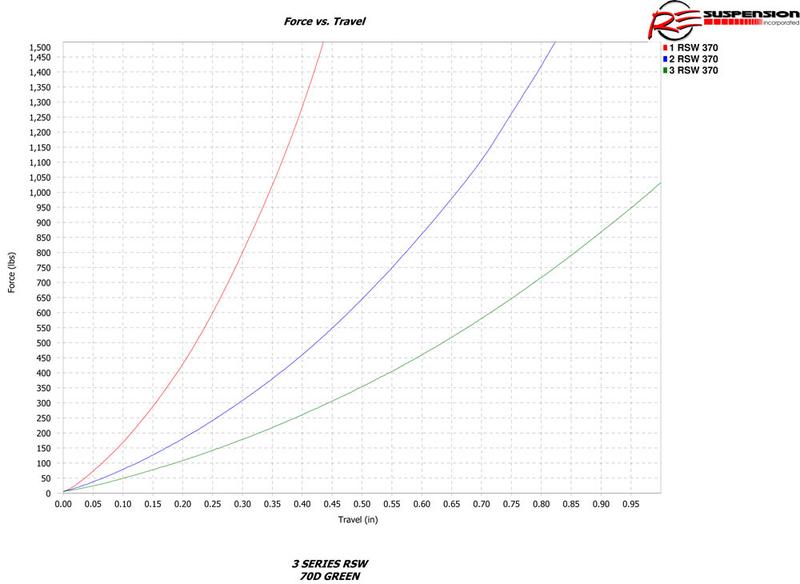

Most common Torque Absorbers have 1 Poly Bump Stop on the Decel Side & 2 on the Accel Side. It's not uncommon to use more than 2 Poly Bump Stops on the acceleration side of the Torque Absorber & 1 or 2 hard Poly Bump Stop on the Decel Side. Some torque absorbers use springs or a combination of springs & Poly Bump Stops. No spring is as progressive as Poly Bump Stops when they get near their max. See chart. The only unit that is more progressive than a good Poly Bump Stop, is an Air Spring Bump Stop. More on this later.

* The image above makes it appear like the lower links & top link are outside the frame rails. The top link is always inside the frame rails & offset to a specific amount to the passenger side. Factory frame rails are quite wide, so the lower links mount on the inside. Track-Warrior frame rails are made narrower, so the lower links can mount on the outside.

Poly Bump Stops compress at a rate & distance determined by the load rate & number of Poly Bump Stops. You need to understand how rate & distance change with the number of Bump Stops and/or the hardness of the Poly Bump Stop. The durometers and exact rates depend on the brand of Poly Bump Stop you utilize. I typically run RE Suspension, Allgaier & Right Foot. Regardless, they all have a range something like 93. 90, 85, 80, 75, 70, 60 & 50 durometer (with an "A" Shure tip).

For conversation, let's say we have 1 red 85 durometer 1.00" tall Poly Bump Stop on the decel side. For conversation, let's say we'll see 1200# of force on deceleration. See chart below. Look at the red line. On the left side, go up to 1200# of force, then across (right) to the red line, then down to the Bump Stop compression at the bottom. You see the red 1.00" tall Bump Stop compressed .30" very aggressively. If we wanted to do this less aggressively & hits ofter on braking, we could run 2 reds on the decel side (assuming space available). Look at the blue line. That is two red 85 durometer 1.00" tall Poly Bump Stops "stacked." Note at 1200# of load on decel, the two of them compressed a total of about .57" ... about double. Look at the green line. That is if we ran 3. That's compressing the 3 reds .85".

On acceleration, I like the Accel Side Poly Bump Stops to compress about 1". Not going to do that with a single 1" poly bump. Frankly 2 of them compressing 1/2" each is a formula for failure. The poly bumps will split & pop off the shaft, somewhere on the exit of turn 6 at Webefast speedway. Running 3 is good, 4 is better, 5 is best ... to compress 1". The more Poly Bump Stops you run, less compression on each & they all have a longer life.

Some racers mix colors (different durometers & load ratings). I do not. The reason is the softest Bump Stop will compress the most & fail first. In my experience with poly bumps, running them all the same rate works best. Just as a note, if you're running a race car with poly bumps, you will need some kind of maintenance schedule to replace them, just like spark plugs & brake pads. The exception is if you run Air Spring Bump Stops. You don't replace them, you simply new seals in once a year.

Under hard acceleration we may see anywhere from 600# to 1500# load, depending on engine power, gear ratios & what transmission gear you're in. (Remember: gears are torque multipliers). For conversation sake, let's say we're expecting 1000# of load & want 1.00" Bump Stop compression.

The reason I like to compress the Bump Stops around 1.00" on the Accel Side, is the longer the travel, the better the shock reduction on the rear tires. If we ran 1 red 85 durometer 1.00" tall Poly Bump Stop on the accel side, we'd only compress it .25". That would be very little shock reduction to the rear tires. Look at the red graph above. Not going to get there with 3 reds. We'd only have .70" travel.

Race companies make torque absorbers in sizes to run from 3 (1" tall) poly bumps to 6. These utilize 2 separate shafts for decel & accel. With shaft length changes you can achieve just about any number of Poly Bump Stops on either end. Let's assume we have room in our rear suspension area to package a 5-Poly Bump Stop torque Absorber. I'd run 2 85 durometer reds on the decel side & 3 (70 durometer) poly bumps on the accel side. See graph below. The green line is 3 (70 durometer) poly bumps stacked, and that gets us right about 1.00" of compression with 1000# load. That will take a LOT of shock out of the tires produced by our bad boy motor ... allowing us to roll the throttle on more aggressively ... running faster lap times.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Racing is a Compromise ... Usually

The reality for all rear suspension designs ... except two ... is the Anti-Squat settings are always a compromise for corner entry & exit handling. With a 3-Link, 4-Link, Torque Arm, Truck Arm, IRS, etc., etc., if you shorten up the swing arm length (increasing the anti-squat percentage) to provide better rear grip on corner exit ... at some point short of optimum corner exit rear grip ... the car starts getting loose on corner entry. (The rear tires are being unloaded & lose rear grip.)

You do not want a pavement car to be loose on corner entry. That's not the fast way around the track. So, you end up with a compromise that is the "best corner exit grip, without being loose on entry." I've seen Racers do it the other way around. They lengthen the swing arm length (decreasing the anti-squat percentage) to provide better rear grip on corner entry. The goal is to drive it in deeper. At some Anti-Squat percentage short of optimum corner entry rear grip ... the car starts getting bad loose on corner exit. The rear tires just loose traction too easy & spin, killing the lap times.

To summarize this, with all rear suspensions (except the Decoupled versions) the rear anti-squat percentage is the same on corner entry & exit ... and that is a compromise. Depending on your priorities ... corner entry or corner exit ... you are tuning the Anti-Squat percentage to find the best compromise, that produces the quickest laps (or in some cases the happiest Driver.)

To clarify how all rear suspensions work, in linkage style suspensions, the links are placed to act as a lever. In IRS the control arms are placed to act as a lever. All rear suspensions have this lever. It just looks different & can be installed with various degrees of Anti-Squat. Anti-Squat is simply a term for this leverage.

Under throttle we have the torque of the engine going through the rear axle & this lever. If your rear suspension is set for 40% Anti-Squat, approximately 40% of that torque (there are other factors) is used to lift the car's CG mass & apply a significant degree of the car's weight as load on the rear tires for traction under acceleration. If we have 60% Anti-Squat, approximately 60% of that torque (there are other factors) is used to lift the car's CG mass & apply some degree of the car's weight as load on the rear tires for traction under acceleration.

Now, as Paul Harvey used to say, "for the rest of the story." Under braking we have the torque of the brakes going the opposite direction through the rear axle & this lever. If your rear suspension is set for 40% Anti-Squat, approximately 40% of that torque is used to pull on the car's CG mass. This REMOVES a significant degree of the car's weight as load on the rear tires ... reducing the traction under deceleration.

Anti-Squat is NOT our friend under braking! Under braking, that same lever that loads the rear tires on acceleration, is UNLOADING the rear tires on deceleration. The more Anti-Squat you run to help the grip on corner exit, the looser the car is on corner entry under braking. It is always a compromise.

What Racers do with adjustable rear suspensions is to tune it until the car starts getting "free" on corner entry. Adjustable 3-Links & 4-Links are adjusting the angle of the top link down in front or up in the rear ... bit by bit ... until they find the best handling balance for their preference or priorities. Most Racers want to leave the lower links level, so they do not introduce any roll steer into their race cars. For conversation sake only ... most Road Race cars end up in the 40% to 60% range of Anti-Squat.

Torque Arm rear suspensions are not as tunable. Again, most Racers want to leave the lower links level, so they do not introduce any roll steer into their race cars. That leaves very little height tuning range, if any, for the Torque Arm. The biggest factor to define the Anti-Squat percentage is the length of the Torque Arm itself. Most are not length adjustable, although I have seen designs that are. So, when deciding on a Torque Arm, it's wise to work out a length that gets you into the 40% to 60% range of Anti-Squat.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Offset Decoupled 3-Link Race Suspensions

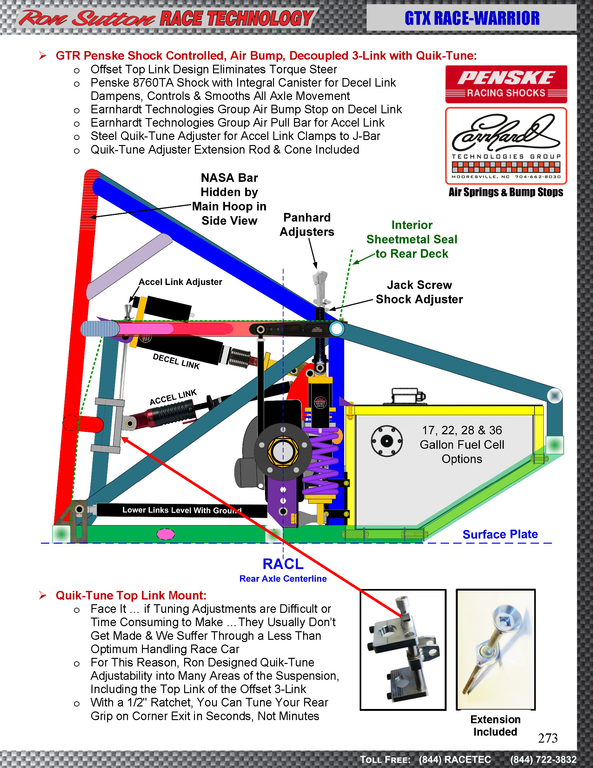

I love Decoupled 3-Link rear suspensions. They are the highest grip rear suspension possible, with the occasional exception on REALLY rough tracks, or serious curb jumping, where an independent rear suspension may be equal or slightly superior. On most race tracks, even with curb jumping, the shock controlled Decoupled 3-Link will outperform independent rear suspensions for grip.

But, we're going to start with my least favorite of my favorite rear suspensions ... the Poly Bump Stop Decoupled 3-Link. I'd better clarify, my race teams have won a boatload of races with this poly unit. For racing, the Poly Bump Stop Decoupled 3-Link is superior to any other straight axle rear suspension ... except the Air Spring Bump Stop and/or shock controlled Decoupled 3-Links.

There are a lot of racing series & classes (NASCAR, Trans Am, SCCA, etc.) that put in a rule to prevent Racers from running the shock controlled Decoupled 3-Link. The rule simply states the race car can only have four shocks. I have run race cars in many road race & oval track series with this rule. So, we ran the Poly Bump Stop Decoupled 3-Link and had an advantage that led to many, many race wins.

The only rear suspensions that do NOT have to be a compromise of corner exit grip & corner entry grip are Decoupled 3-Links & Decoupled Torque Arms. I prefer the Decoupled 3-Link because they are more tunable than the Decoupled Torque Arm. The top link defining the acceleration characteristics is not coupled or connected solidly to the other top link defining the deceleration characteristics. That is why the word "Decoupled" is used.

In my racing experience Decoupled 3-Link is hands down the best route. I LOVE Decoupled 3-Links, because we can fine tune the corner exit grip to be 100% dead nuts optimum ... and the corner entry grip to be 100% dead nuts optimum ... completely independent of each other. The Accel link Sets Anti-Squat for Acceleration & the Decel link Sets Pro-Squat for Braking. No other rear suspension offers that.

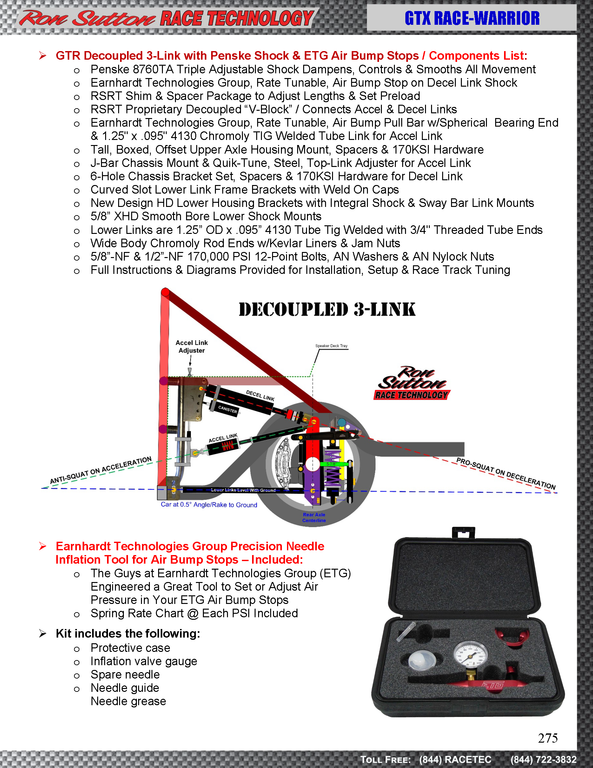

As you can see in the illustration above, the "Accel Link" is in the typical location a top link would be in any 3-Link. In this example, the Accel Link is spring loaded & the front chassis mount is adjustable with a fine tuning jack screw adjuster. We can adjust the front of the Accel Link either direction by 1/16" of an inch or 2" if we want.

The angle of the Accel Link intersects with the angle of the level lower links in front of the Rear Axle Centerline (RACL) to achieve a percentage of Anti-Squat anywhere from 25% to well over 100%. Remember, with all other rear suspensions, most Road Race cars end up in the 40% to 60% range of Anti-Squat, as a compromise, so as not to be too loose on entry or exit. On Decoupled 3-Link rear suspensions we find Anti-Squat in the 90% to 100% range makes the race car launch off the corners. And there are no side effects. The rear grip on corner entry under braking is NOT affected by the Accel Link ... BECAUSE it DECOUPLES under braking.

Drivers LOVE it. But they really love the difference on corner entry. Again, most Road Race cars end up in the 40% to 60% range of Anti-Squat, as a compromise, so as not to be too loose on entry or exit. Not with Decoupled 3-Link rear suspensions.

The Decel link runs the reverse angle ... downhill to the rear ... and intersects with the angle of the level lower links BEHIND the Rear Axle Centerline (RACL). Instead of having some percentage of Anti-Squat ... it has NO ANTI-SQUAT on deceleration ... it has PRO-SQUAT.

What is Pro-Squat? The opposite of Anti-Squat. Under braking, the rear brake torque is lifting on the CG of the race car's mass to LOAD the rear Tires. On Decoupled 3-Link rear suspensions we find 100% Pro-Squat makes the race car amazingly stable under hard, threshold braking on corner entry. And there are no side effects. The rear grip on corner exit under acceleration is NOT affected by the Decel link ... BECAUSE it DECOUPLES under throttle.

Frankly it works so well, we run larger piston rear calipers to increase the rear braking force. The more rear braking force, the more it loads the rear tires.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

There are Different Methods of Controlling the Travel Each Direction ... Poly Bump Stops, metal springs, Air Spring Bump Stops & shocks. The Poly Bump Stop Decoupled 3-Link works great! Not as good as the shock versions, but very well. These are the same Poly Bump Stops utilized in the Torque Absorbers mentioned above. The Poly Bump Stop works the same, so read that section if you did not.

One drawback is Poly Bump Stops wear out from being loaded & unloaded 10-12 times a lap. Just like Poly Bump Stops in the front shocks or Torque Absorbers. When they get abused too much, the Poly Bump Stop splits & pops out. Same front or rear. Not good if it happens on track during a race. We simply changed them on a scheduled basis to prevent that. And we learned using multiple Poly Bump Stops together (Shown Here) spreads the load over that number of bushings & lengthens the life of the bushings. Two bushings will live twice as long as one. Four bushings will live twice as long as two. But they still need to be replaced with scheduled maintenance.

Many Racers ask why we don't run metal bump springs instead. They last longer, although not forever either. The reason is bump springs are not ... can not be ... as progressive on rates as the Poly Bump Stops are. Yes, I'm aware of progressive springs. But the progression rate is small. Too small for our needs.

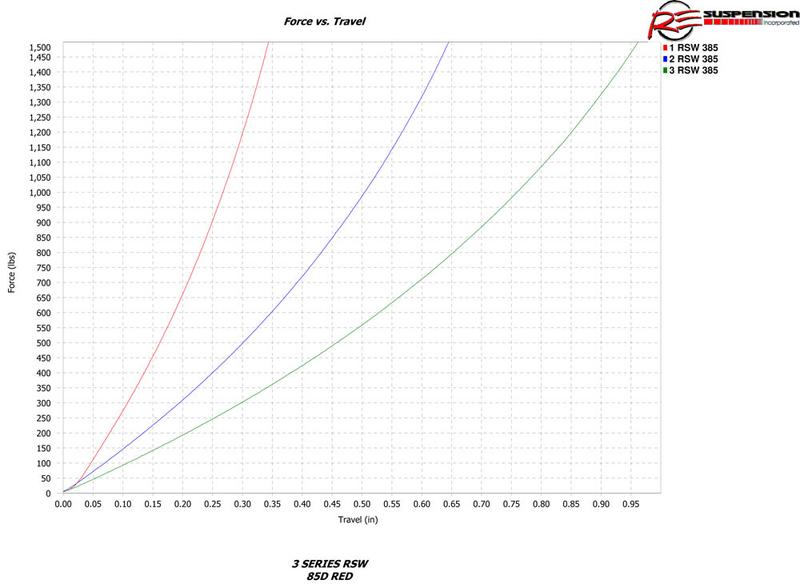

Recently, Earnhardt Technologies Group (ETG) developed Air Spring Bump Stops that we have utilized in place of the Poly Bump Stops. Like Poly Bump Stops, the ETG Air Spring Bump Stops have a similar, very progressive rate curve to them. (See chart) This is perfect for our needs, as we want the initial compression to be soft & quick ... then to have the rate increase to slow down the sudden stop.

The Earnhardt Technologies Air Spring Bump Stops have several advantages over the Poly Bump Stops. Number one. They don't split & pop out! Second, we can tune them without taking them off, by changing the air pressure in them. The chart to the right shows the rate changes with air (Nitrogen) PSI changes. The ETG Air Spring Bump Stops come in four travel versions from 1/2" to 2" to fit our needs.

They can be used on regular Torque Absorber & Poly Bump Stop Decoupled 3-Link linkages, but we utilize the ETG "Bump Stick." It bolts in place of the shock. Frankly, it makes it easy to go back & forth between shock controlled ... with an Air Spring Bump Stop on the shock ... or just Air Spring Bump Stop controlled (with no shock) depending on the rules where the race car is run.

We have a version that only uses ETG Air Bump Stops ... and no shock ... that is legal for SCCA GT classes & Trans Am. On the Decel side ... when the Driver lifts off the throttle & applies initial braking ... the top link mount comes back that same 1.00" to 1.25" plus another .25" to .50" to "help" soften the transition. I used the word "help" intentionally, as one of the few cons of the poly Bump Stops & the Air Spring Bump Stops, is there is no shock valving to slow these transitions.

The top of the rear axle pulling on the Accel side under hard acceleration is relatively smooth. But the system hits pretty hard on the Decel side, when the Driver gets off throttle & on the brakes. Not enough to upset the chassis. But enough to irritate the Driver if they're not used to it. The image above shows an open shaft. We place the ETG Air Bump Stops, spacers & shims to fill that gap.

For that Accel Link, we utilize ETG's 2" travel "Pull Bar". Same technology & progressive spring rate as the Air Spring Bump Stops. Both have travel indicators. We like to 1.00" to 1.25" pull on the Accel Link. That amount of pull allows us to control the engine power from shocking the tire very well. Any more than that and we risk the rear axle hitting the watts link or other stuff back there. Any less than that & we find the system is not as effective at reducing the shock to the tires when the Driver cracks open the throttle. Especially with short sidewall tires on 18" wheels.

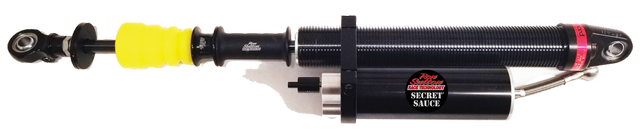

This is where the shock controlled versions of the Decoupled 3-Link shine. The unique shock valving we run smooths out the travel each direction. The Driver can still feel the stops each way, but it is minor. Believe it or not, the top link of the rear axle moves so much faster than any wheel on the race car. So, the valving is VERY different. To manage this well, the shocks we use have to be ultra quick responding. No twin tube crap. Only monotube shocks, with decoupled pistons & separation gas canisters will perform optimally.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

With a Decoupled 3-Link rear suspension, we have a shared top rear axle housing mount (see below) that the Accel & Decel links attach to with a special V-block we make. The chassis mounts tie into the roll cage via a "J-Bar" assembly. You can see the upper brackets for the Decel link weld on & the lower adjustable mount clamps on the J-Bar. It has 4" of adjustability range, but can be unclamped, moves & reclamped on the J-Bar. The J-Bar welds to the rear crossmember. You can see it in the photo below next to the half round laser cut out for the driveshaft loop. This setup runs the exhaust down the passenger side of the car.

In the photo above, you can see how the J-Bar attaches to both cross bars in the main hoop of the roll cage. The top mount is gusseted both ways. You can see here in this photo, the rear crossmember has a gap. That is for the exhaust to come down the tunnel. The J-Bar always mounts to the passenger side of the roll cage.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The ARS shock shown above & below is the fastest responding shock on the racing market. It works excellent as long as we don't overheat it. It is a monotube shock with a small diameter decoupled piston. This piston allows the shocks to respond to small inputs (track surfaces) separate from the faster & longer stroke of acceleration & deceleration.

You can see how the decoupled 3-Link Accel & Decel system work in this video here:

It is of an autocross car just testing in a parking lot, so take that into account. But this shock in the video is not the decoupled piston.

The decoupled piston keeps the tires planted over irregularities. Then under hard acceleration the rebound valving allows the shock to extend fast, but smoothly. On Decel, the valving slows the shock compression significantly to take the violence out of the transition to braking. We like this shock up to 1000HP on track cars that see 5-10 laps or 750Hp if they're going to run 30 laps.

Anytime we're going to see more laps, or we have a lot more power to control, we step up to either Penske 8300DA or 8760TA shocks, with larger OD decoupled pistons, provide more control. The additional oil volume of these shocks allows them to see more abuse without running hot & thinning out the shock fluid. You can see these & the ETG Air Spring Bump Stops in the images below in our Race-Warrior underslung rear frame clip.

#57

Front Suspension & Steering Geometry for Track & Racing / Re: Front Suspension & Steerin...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Dec 07, 2025, 02:13 PMUnderstanding Front Roll Centers:

Before we delve into the details of Front Roll Centers (FRC) ... I think it's helpful for Racers to take several steps back & look at the big picture of handling ... to better understand the role of the FRC with the rest of the car.

Total weight ... weight distribution front to rear ... and height of this weight (CG) act like a lever over the roll centers. As discussed earlier, lowering the CG shortens that lever, as does raising the RC ... but works the tires less. Raising the CG lengthens that lever, as does lowering the RC ... and works the tires more.

Our goal is to move them both ... to the degree possible ... where we find the optimum balance of working the tires & Roll Angle. If it is a clean sheet a paper race car design, like I do often, the goal is to get the CG as low as possible ... the FRC at 0.00" in full dive, roll & steer (15°) ... and the RRC at the lowest height (spring rate dependent) that achieves neutral handling balance

Picking the target front Roll Center for road course racing is often based on priorities ... and the understanding of three things:

1. Tighter corners need the FRC lower & faster, sweeping corners need it higher.

2. How far the front end has dived in each corner.