Recent posts

#61

Track Tuning Techniques for Overall Handling Balance / Track Tuning for Overall Handl...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Dec 06, 2025, 06:44 PMTrack Tuning for Overall Handling Balance

Welcome,

I promise to post advice only when I have significant knowledge & experience on the topic. Please don't be offended if you ask me to speculate & I decline. I don't like to guess, wing it or BS on things I don't know. I figure you can wing it without my input, so no reason for me to wing it for you.

A few guidelines I'm asking for this thread:

1. I don't enjoy debating the merits of tuning strategies with anyone that thinks it should be set-up or tuned another way. It's not fun or valuable for me, so I simply don't do it. Please don't get mad if I won't debate with you.

2. If we see it different ... let's just agree to disagree & go run 'em on the track. Arguing on an internet forum just makes us all look stupid. Besides, that's why they make race tracks, have competitions & then declare winners & losers.

3. To my engineering friends ... I promise to use the wrong terms ... or the right terms the wrong way. Please don't have a cow.

4. To my car guy friends ... I promise to communicate as clear as I can in "car guy" terms. Some stuff is just complex or very involved. If I'm not clear ... call me on it.

5. I type so much, so fast, I often misspell or leave out words. Ignore the mistakes if it makes sense. But please bring it up if it doesn't.

6. I want people to ask questions. That's why I'm starting this thread ... so we can discuss & learn. There are no stupid questions, so please don't be embarrassed to ask about anything within the scope of the thread.

7. If I think your questions ... and the answers to them will be valuable to others ... I want to leave it on this thread for all of us to learn from. If your questions get too specific to your car only & I think the conversation won't be of value to others ... I may ask you to start a separate thread where you & I can discuss your car more in-depth.

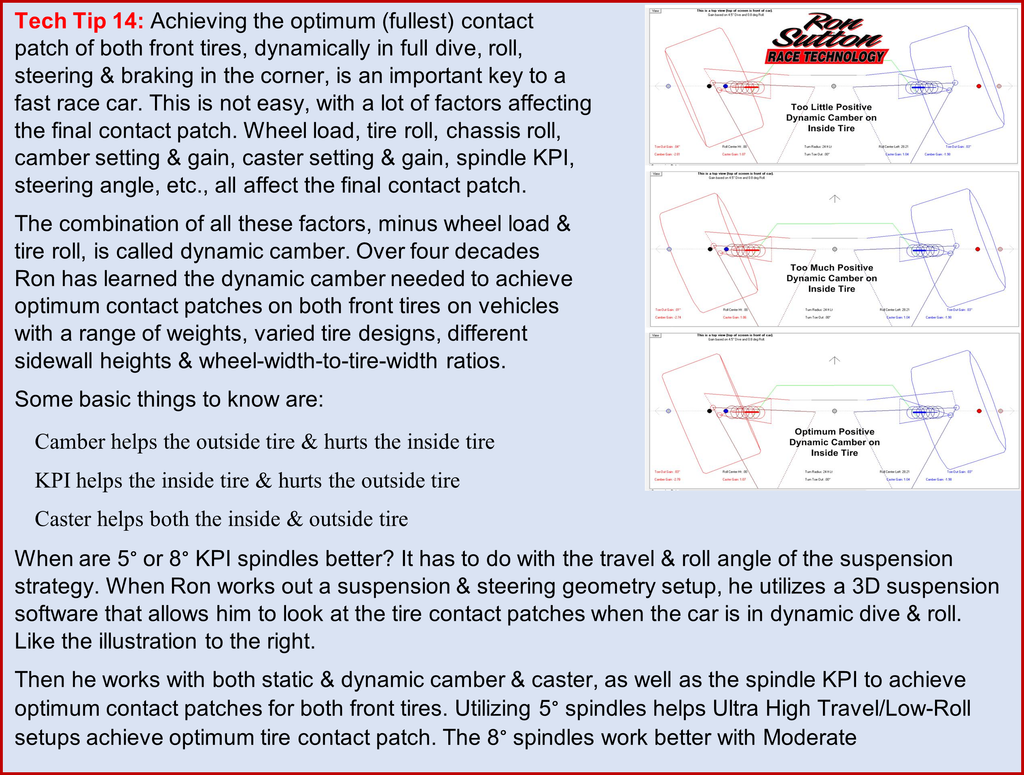

8. Some people ask me things like "what should I do?" ... and I can't answer that. It's your hot rod. I can tell you what doing "X" or "Y" will do and you can decide what makes sense for you.

9. It's fun for me to share my knowledge & help people improve their cars. It's fun for me to learn stuff. Let's keep this thread fun.

10. As we go along, I may re-read what I wrote ... fix typos ... and occasionally, fix or improve how I stated something. When I do this, I will color that statement red, so it stands out if you re-skim this thread at some time too.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Let's Clarify the Cars We're Discussing:

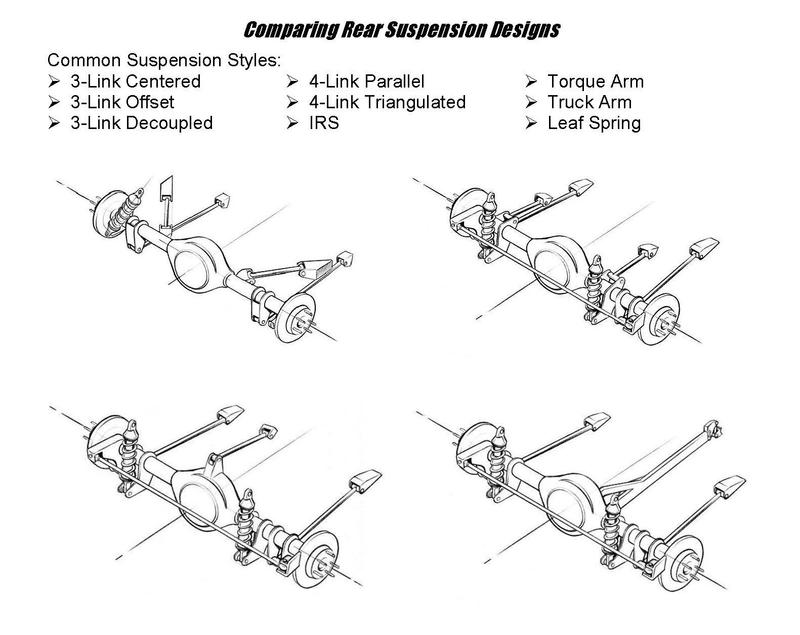

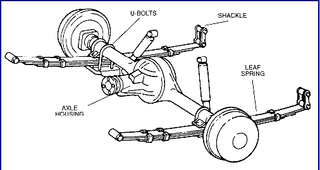

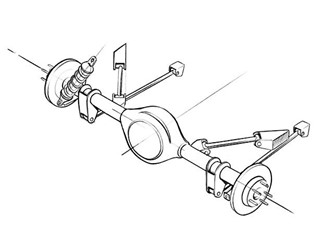

We're going to keep the conversation to typical full bodied Track & Road Race cars ... front engine, rear wheel drive ... with a ride height requirement of at least 1.5" or higher. They can be tube chassis or oem bodied cars ... straight axle or IRS ... with or without aero ... and for any purpose that involves road courses or autocross.

But if the conversation bleeds over into other types of cars too much ... I may suggest we table that conversation. The reason is simple, setting up & tuning these different types of cars ... are well ... different. There are genres of race cars that have such different needs, they don't help the conversation here.

In fact, they cloud the issue many times. If I hear one more time how F1 does XYZ ... in a conversation about full bodied track/race cars with a X" of ride height ... I may shoot someone. Just kidding. I'll have it done. LOL

Singular purpose designed race cars like Formula 1-2-3-4, Formula Ford, F1600, F2000, etc, Indy Cars, IMSA Prototypes, Open Wheel Midgets & Sprint Cars. First, none of them have a body that originated as a production car. Second, they have no ride height rule, so they run almost on the ground & do not travel the suspension very far. Formula 1-2-3-4, Formula Ford, F1600, F2000, etc, Indy Cars, IMSA Prototypes are rear engine. The Open Wheel Midgets & Sprint Cars are front engine & run straight axles in front.

I have a lot of experience with these cars & their suspension & geometry needs are VERY different than full bodied track & road race cars with a significant ride height. All of them have around 60% rear weight bias. That changes the game completely. With these cars we're always hunting for more REAR grip, due to the around 60%+/- rear weight bias.

In all my full bodied track & road race cars experience ... Stock Cars, Road Race GT cars, TA/GT1, etc. ... with somewhere in the 50%-58% FRONT bias ... we know we can't go any faster through the corners than the front end has grip. So, what we need to do, compared to Formula 1-2-3-4, Formula Ford, F1600, F2000, etc, Indy Cars, IMSA Prototypes, Open Wheel Midgets & Sprint Cars, is very different.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Before we get started, let's get on the same page with terms & critical concepts.

Shorthand Acronyms

IFT = Inside Front Tire

IRT = Inside Rear Tire

OFT = Outside Front Tire

ORT = Outside Rear Tire

*Inside means the tire on the inside of the corner, regardless of corner direction.

Outside is the tire on the outside of the corner.

LF = Left Front

RF = Right Front

LR = Left Rear

RR = Right Rear

ARB = Anti-Roll Bar (Sway Bar)

FLLD = Front Lateral Load Distribution

RLLD = Rear Lateral Load Distribution

TRS = Total Roll Stiffness

LT = Load Transfer

RA = Roll Angle

RC = Roll Center

CG = Center of Gravity

CL = Centerline

FACL = Front Axle Centerline

RACL = Rear Axle Centerline

UCA = Upper Control Arm

LCA = Lower Control Arm

LBJ = Lower Ball Joint

UBJ = Upper Ball Joint

BJC = Ball Joint Center

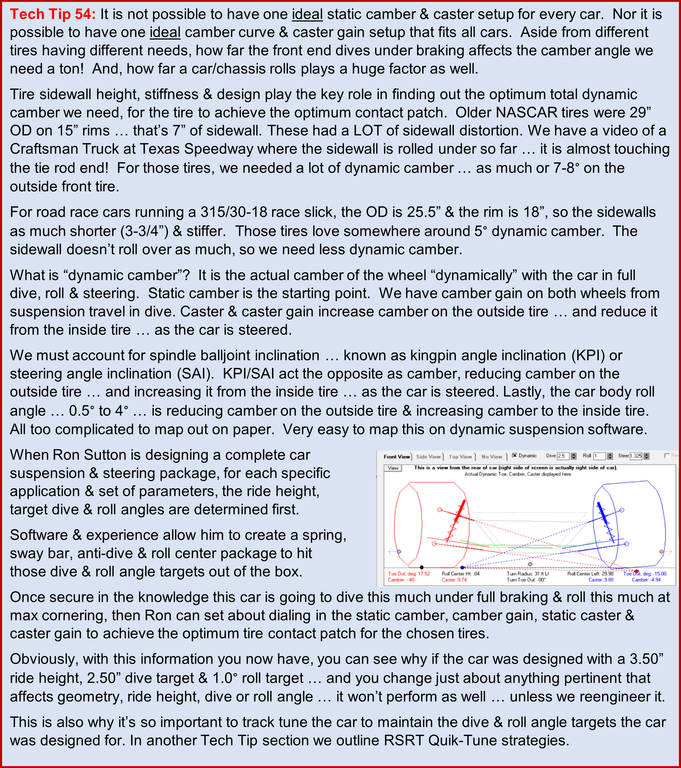

IC = Instant Center is the pivot point of a suspension assembly or "Swing Arm"

CL-CL = Distance from centerline of one object to the centerline of the other

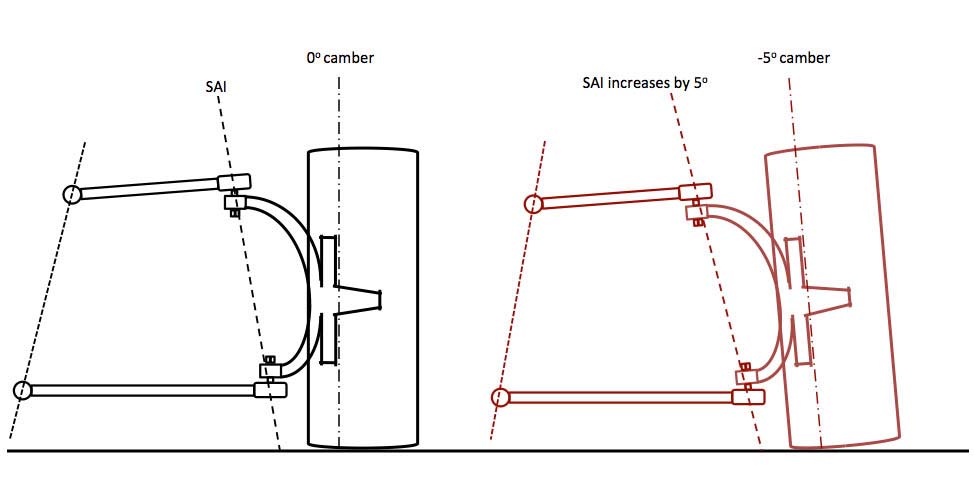

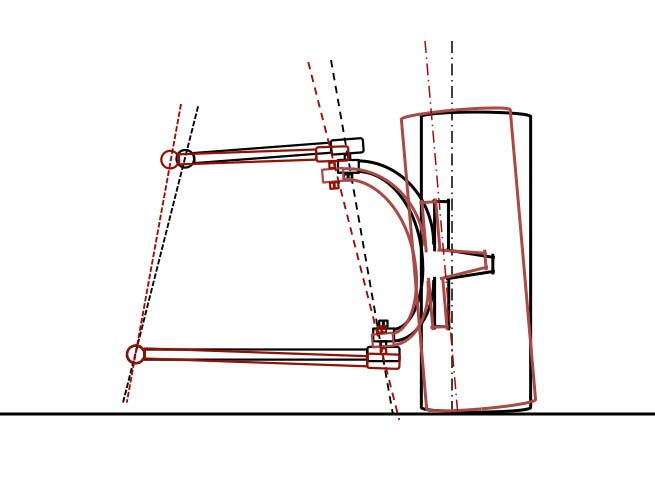

KPI = King Pin Inclination, an older term for the angle of the ball joints in relation to the spindle

SAI = Steering Angle Inclination, a modern term for the angle of the ball joints in relation to the spindle

TERMS:

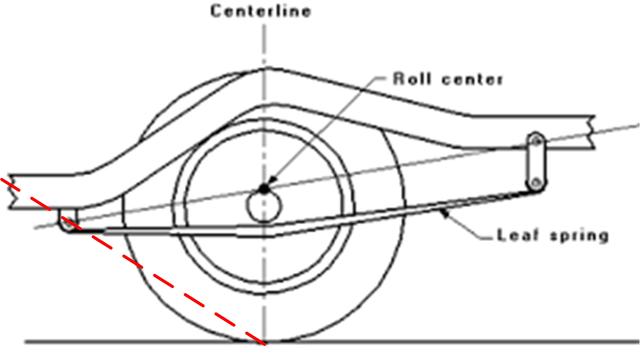

Roll Centers = Cars have two Roll Centers ... one as part of the front suspension & one as part of the rear suspension, that act as pivot points. When the car experiences body roll during cornering ... everything above that pivot point rotates towards the outside of the corner ... and everything below the pivot point rotates the opposite direction, towards the inside of the corner.

Center of Gravity = Calculation of the car's mass to determine where the center is in all 3 planes. When a car is cornering ... the forces that act on the car to make it roll ... act upon the car's Center of Gravity (CG). With typical production cars & "most" race cars, the CG is above the Roll Center ... acting like a lever. The distance between the height of the CG & the height of each Roll Center is called the "Moment Arm." Think of it a lever. The farther apart the CG & Roll Center are ... the more leverage the CG has over the Roll Center to make the car roll.

Instant Center is the point where a real pivot point is, or two theoretical suspension lines come together, creating a pivot arc or swing arm.

Swing Arm is the length of the theoretical arc of a suspension assembly, created by the Instant Center.

Static Camber is the tire angle (as viewed from the front) as the car sits at ride height. Straight up, 90 degrees to the road would be zero Camber. Positive Camber would have the top of tire leaned outward, away from the car. Negative Camber would have the top of tire leaned inward, towards the center of the car.

Camber Gain specifically refers to increasing negative Camber (top of wheel & tire leaning inward, towards the center of the car) as the suspension compresses under braking & cornering.

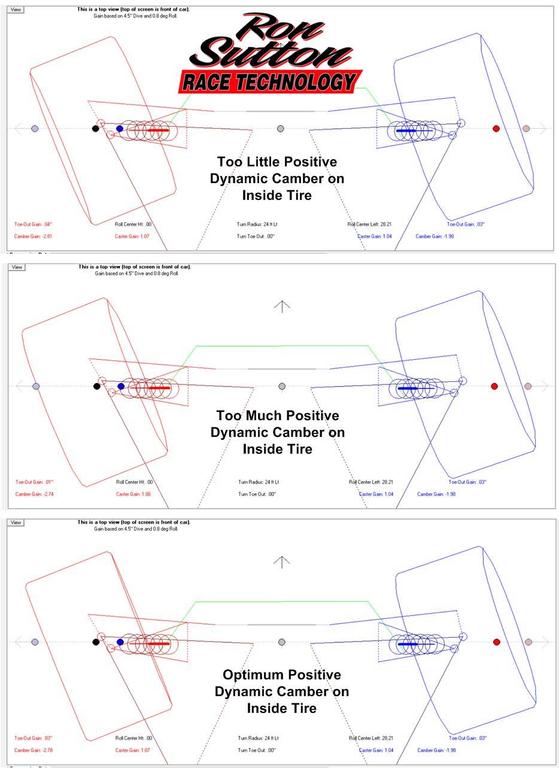

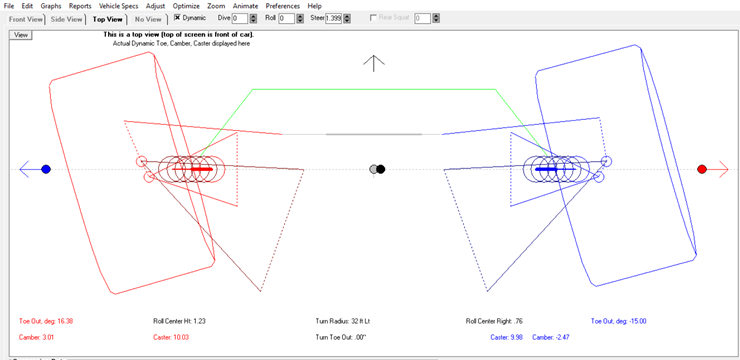

Total Camber is the combination of Static Camber & Camber Gain ... under braking, in dive with no roll & no steering, as well as the Dynamic Camber with chassis roll & steering.

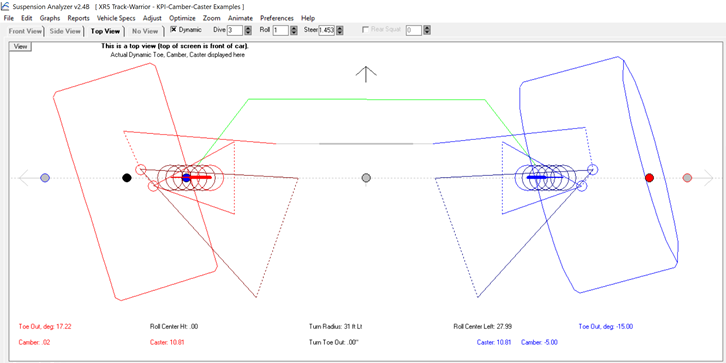

Dynamic Camber refers to actual angle of the wheel & tire (top relative to bottom) ... compared to the track surface ... whit the suspension in dive, with full chassis roll & a measure of steering. In others, dynamically in the corner entry. For our purposes, we are assuming the car is being driven hard, at its limits, so the suspension compression & chassis/body roll are at their maximum.

Static Caster is the spindle angle (viewed from the side with the wheel off). Straight up, 90 degrees to the road would be zero Caster. Positive Caster would have the top of spindle leaned back toward to cockpit. Negative Caster would have the top of spindle leaned forward towards the front bumper.

Caster Gain is when the Caster angle of the spindle increases (to the positive) as the suspension is compressed, by the upper ball joint migrating backwards and/or the lower ball joint migrating forward ... as the control arms pivot up. This happens when the upper and/or lower control arms are mounted to create Anti-dive. If there is no Anti-dive, there is no Caster Gain. If there is Pro-Dive, there is actually Caster loss.

Anti-Dive is the mechanical leverage to resist or slow compression of the front suspension (to a degree) under braking forces. Anti-dive can be achieved by mounting the upper control arms higher in the front & lower in the rear creating an angled travel. Anti-dive can also be achieved by mounting the lower control arms lower in the front & higher in the rear, creating an angled travel. If both upper & lower control arms were level & parallel, the car would have zero Anti-dive.

Pro-Dive is the opposite of Anti-dive. It is the mechanical leverage to assist or speed up compression of the front suspension (to a degree) under braking forces. Provide is achieved by mounting the upper control arms lower in the front & higher in the rear, creating the opposite angled travel as Anti-Dive. Pro-dive can also be achieved by mounting the lower control arms higher in the front & lower in the rear, creating the opposite angled travel as Anti-Dive.

Split is the measurement difference in two related items. We would say the panhard bar has a 1" split if one side was 10" & the other side 11". If we had 1° of Pro-Dive on one control arm & 2° of Anti-Dive on the other, we would call that a 3° split. If we have 8° of Caster on one side & 8.75° on the other, that is a .75° split.

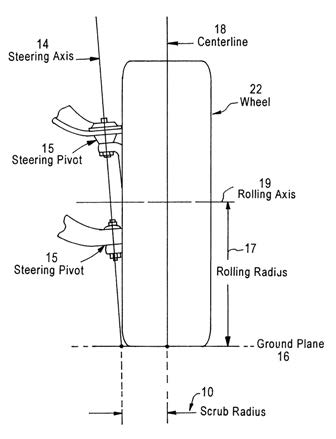

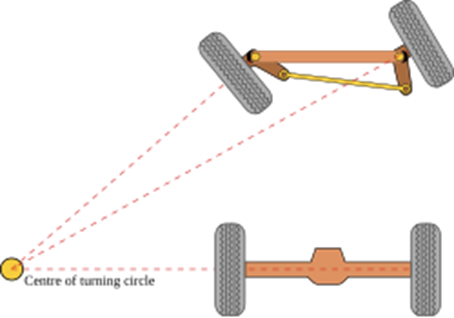

Scrub Radius = A car's Scrub Radius is the distance from the steering axis line to tread centerline at ground level. It starts by drawing a line through our upper & lower ball joints, to the ground, that is our car's steering axis line. The dimension, at ground level, to the tire tread centerline, is the Scrub Radius. The tire's contact patch farthest from the steering axis loses grip earliest & most during steering. This reduces the tire's grip on tight corners. The largest the Scrub Radius, the more pronounced the loss of grip is on tight corners. Reducing the Scrub Radius during design increases front tire grip on tight corners.

Baseline Target is the package of information about the car, like ride height, dive travel, Roll Angle, CG height, weight, weight bias, tires & wheel specifications, track width, engine power level, estimated downforce, estimated max corner g-force, etc. We call it "Baseline" ... because it's where we're starting at & "Target" because these key points are the targets we're aiming to achieve. We need to work this package of information prior to chassis & suspension design, or we have no target.

Total Roll Stiffness (aka TRS) is the mathematical calculation of the "roll resistance" built into the car with springs, Sway Bars, Track Width & Roll Centers. Stiffer springs, bigger Sway Bars, higher Roll Centers & wider Track Widths make this number go UP & the Roll Angle of the car to be less. "Total Roll Stiffness" is expressed in foot-pounds per degree of Roll Angle ... and it does guide us on how much the car will roll.

Front Lateral Load Distribution & Rear Lateral Load Distribution (aka FLLD & RLLD):

FLLD/RLLD are stated in percentages, not pounds. The two always add up to 100% as they are comparing front to rear roll resistance split. Knowing the percentages alone, will not provide clarity as to how much the car will roll ... just how the front & rear roll in comparison to each other. If the FLLD % is higher than the RLLD % ... that means the front suspension has a higher resistance to roll than the rear suspension ... and therefore the front of the car runs flatter than the rear of the suspension ... which is the goal.

Roll is the car chassis and body "rolling" on its Roll Axis (side-to-side) in cornering.

Roll Angle is the amount the car "rolls" on its Roll Axis (side-to-side) in cornering, usually expressed in degrees.

Dive is the front suspension compressing under braking forces.

Full Dive is the front suspension compressing to a preset travel target, typically under threshold braking. It is NOT how far it can compress.

Rise = Can refer to either end of the car rising up.

Squat = Refers to the car planting the rear end on launch or under acceleration.

Pitch = Fore & aft body rotation. As when the front end dives & back end rises under braking or when the front end rises & the back end squats under acceleration.

Pitch Angle is the amount the car "rotates" fore & aft under braking or acceleration, usually expressed by engineers in degrees & in inches of rise or dive by Racers.

Diagonal Roll is the combination of pitch & roll. It is a dynamic condition. On corner entry, when the Driver is both braking & turning, front is in dive, the rear may, or may not, have rise & the body/chassis are rolled to the outside of the corner. In this dynamic state the outside front of the car is lowest point & the inside rear of the car is the highest point.

Track Width is the measurement center to center of the tires' tread, measuring both front or rear tires.

Tread Width is the measurement outside to outside of the tires' tread. (Not sidewall to sidewall)

Tire Width is the measurement outside to outside of the sidewalls. A lot of people get these confused & our conversations get sidelined.

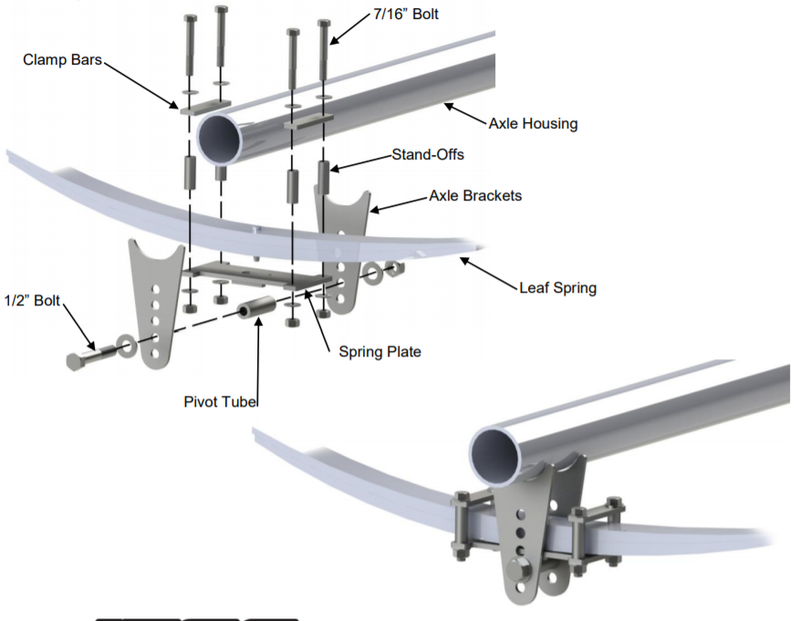

Floating typically means one component is re-engineered into two components that connect, but mount separate. In rear ends, a "Floater" has hubs that mount & ride on the axle tube ends, but is separate from the axle itself. They connect via couplers. In brakes, a floating caliper or rotor means it is attached in a way it can still move to some degree.

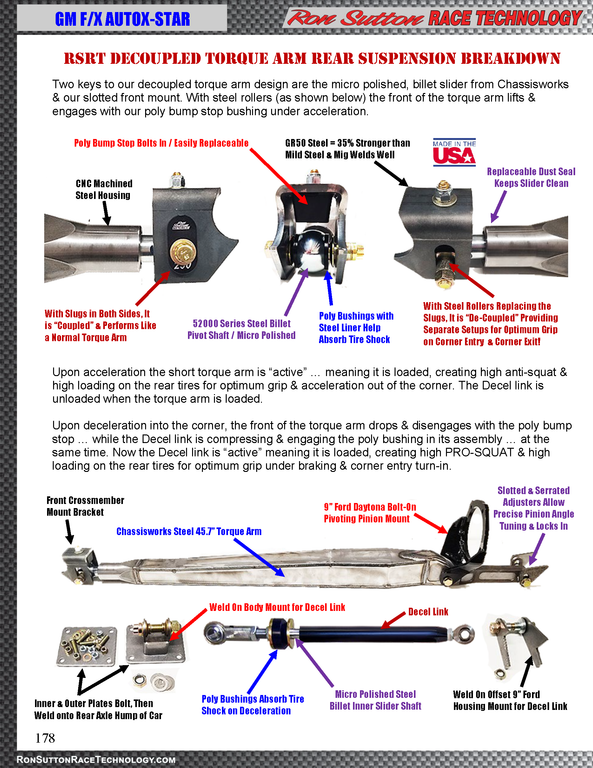

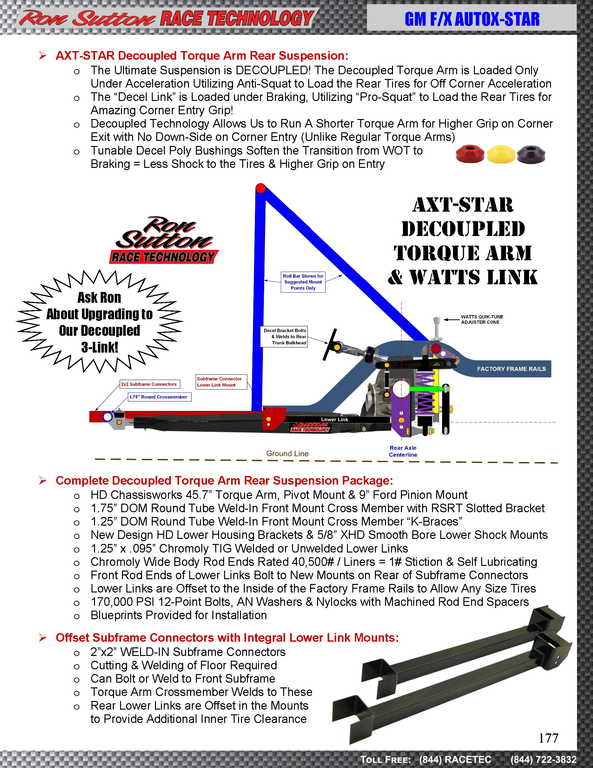

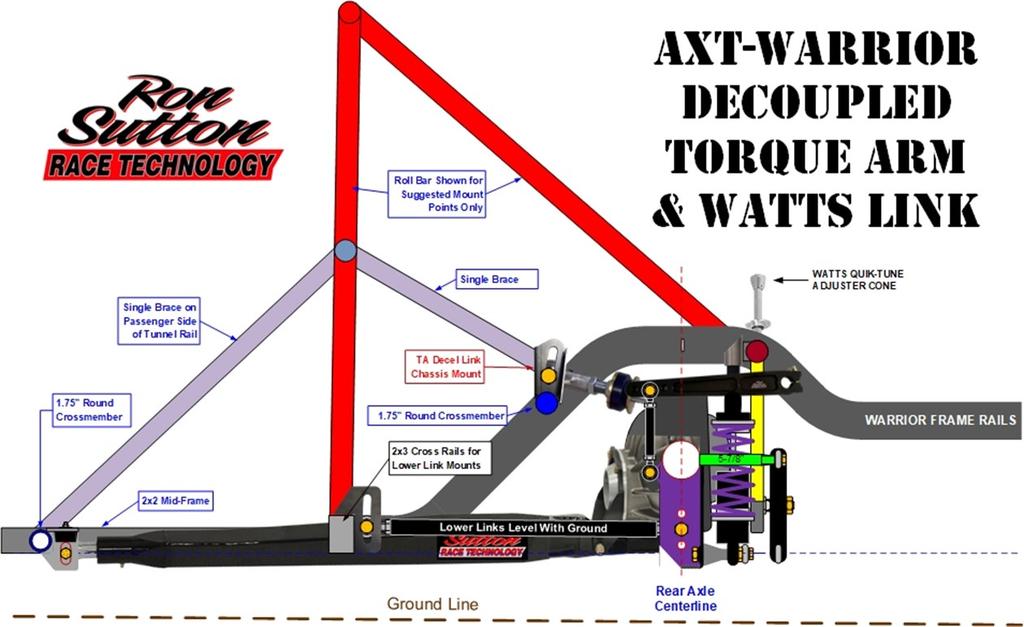

Decoupled typically means one component is re-engineered into two components that connect, but ACT separately. In suspensions, it typically means one of the two new components perform one function, while the second component performs a different function.

Spring Rate = Pounds of linear force to compress the spring 1". If a spring is rated at 500# ... it takes 500# to compress it 1"

Spring Force = Total amount of force (weight and/or load transfer) on the spring. If that same 500# spring was compressed 1.5" it would have 750# of force on it.

Sway Bar, Anti-Sway Bar, Anti Roll Bar = All mean the same thing. Kind of like "slim chance" & "fat chance."

Sway Bar Rate = Pounds of torsional force to twist the Sway Bar 1 inch at the link mount on the control arm.

Rate = The rating of a device often expressed in pounds vs distance. A 450# spring takes 900# to compress 2".

Rate = The speed at which something happens, often expressed in time vs distance. 3" per second. 85 mph. * Yup, dual meanings.

Corner Weight = What each, or a particular, corner of the race car weighs when we scale the car with 4 scales. One under each tire.

Weight Bias = Typically compares the front & rear weight bias of the race car on scales. If the front of the car weighs 1650# & the rear weighs 1350# (3000# total) we would say the car has a 55%/45% front bias. Bias can also apply to side to side weights, but not cross weight. If the left side of the car weighs 1560# & the right 1440#, we would say the car has a 52/42 left side bias.

Cross Weight = Sometimes called "cross" for short or wedge in oval track racing. This refers to the comparison of the RF & LR corner weights to the LF & RR corner weights. If the RF & LR corner scale numbers add up to the same as the LF & RR corners, we would say the car has a 50/50 cross weight. In oval track circles, they may say we have zero wedge in the car. If the RF & LR corner scale numbers add up to 1650# & the LF & RR corners add up to 1350#, we would say the car has a 55/45 cross weight. In oval track circles, they may say we have 5% wedge in the car, or refer to the total & say we have 55% wedge in the car.

Grip & Bite = Are my slang terms for tire traction.

Push = Oval track slang for understeer, meaning the front tires have lost grip and the car is going towards the outside of the corner nose first.

Loose = Oval track slang for oversteer meaning the rear tires have lost grip and the car is going towards the outside of the corner tail first.

Tight is the condition before push, when the steering wheel feels "heavy" ... is harder to turn ... but the front tires have not lost grip yet.

Free is the condition before loose, when the steering in the corner is easier because the car has "help" turning with the rear tires in a slight "glide" condition.

Good Grip is another term for "balanced" or "neutral" handling condition ... meaning both the front & rear tires have good traction, neither end is over powering the other & the car is turning well.

Mean = My slang term for a car that is bad fast, suspension is on kill, handling & grip turned up to 11, etc., etc.

Greedy is when we get too mean with something on the car, too aggressive in our setup & it causes problems.

Steering Turn-In is when the Driver initiates steering input turning into the corner.

Steering Unwind is when the Driver initiates steering input out of the corner.

Steering Set is when the Driver holds the steering steady during cornering. This is in between Steering Turn-In & Steering Unwind.

Roll Thru Zone = The section of a corner, typically prior to apex, where the Driver is off the brakes & throttle. The car is just rolling. The start of the Roll Thru Zone is when the Driver releases the brakes 100%. The end of the Roll Thru Zone is when the Driver starts throttle roll on.

TRO/Throttle Roll On is the process of the Driver rolling the throttle open at a controlled rate.

Trail Braking is the process of the Driver braking while turning into the corner. Typically, at the weight & size of the cars we're discussing here ... the Driver starts braking before Steering Turn-In ... and the braking after that is considered Trail Braking. This is the only fast strategy. Driver's that can't or won't trail brake are back markers.

Threshold Braking = The Driver braking as hard as possible without locking any tires, to slow the car as quickly as possible to the target speed for the Roll Thru Zone. Typically done with very late, deep braking to produce the quickest lap times.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

16 CRITICAL RACE CAR DESIGN CONCEPTS:

A. One of the most important design factors is utilizing all four tires on the track surface for maximum possible adhesion. Shaker Rigs (6, 7 & 8 post rigs) exist to help race car designers, teams & engineers maximize tire contact & loading to the track surface. As a general rule, anything that reduces contact patch and/or tire loading is our enemy & anything that increases contact patch (up to optimum) and/or achieves optimum loading of all four tires is our friend.

B. Weight is our enemy. Lighter race cars do everything better. They turn better. They accelerate better. They decelerate better. They even crash better (safer). They stress all the components less. Building a lighter car allows us to run less heavy duty, lighter suspension components reducing unsprung & rotating mass ... leading to an even lighter, faster race car. Every ounce matters if you are serious about winning.

C. Center of Gravity (aka CG ... aka weight mass) matters ... a lot. The mantra of oval track race car builders when it comes to race car weight is "low, light & left." (More left side weight helps cars turning left.) For road race cars it is "low, light & centered." The goal is to have the lightest race car ... weigh the exact same on all four scales ... with the majority of the mass (CG) low in the car & centered in the cockpit.

When the race series or class has a weight minimum, the Racers that build the car as light as practical, then places weight (lead, steel, tungsten) near the center of the car, down low ... will produce a faster, better handling, safer race car.

D. When we design a race car with a lower center of gravity, it is much easier to drive & can be much faster. A lower center of gravity allows the race car to run flatter through the corners, working all four tires better ... more grip ... more corner speed. A lower center of gravity allows the race car to pitch less (dive & rise) under braking & acceleration, working all four tires better ... more grip ... more corner entry & exit speed. A lower center of gravity makes the race car more stable, higher grip & easier to drive.

E. If we carelessly design a race car with excessive weight (mass) outside the axle centerlines, we're asking for a scary, ill handling, even dangerous handling, race car. Excess weight ahead of the front axle centerline will make the front end of the car swing out when we exceed total tire grip. Big push (understeer) & then nose hard into the outside barrier.

Similar in the rear. Excess weight behind of the rear axle centerline will make the rear end of the car swing out when we exceed total tire grip. Hard loose condition (oversteer) & then back hard into the outside barrier. Designing the race car with as much of its needed mass inside the axle centerlines is critical.

F. Track width is CRITICAL. Racing sanctioning bodies know this & enforce track width rules diligently, because all knowledgeable Racers know that even a small increase in track width can provide a significant advantage. Very similar to having a lower center of gravity ... having a wider track width allows the race car to run flatter through the corners, working all four tires better ... more grip ... more corner speed. A wider track width makes the race car more stable, higher grip & easier to drive.

With exception for tight, narrow autocross courses, designing the race car with the widest track width possible is the goal. Widening the car body, or building a wider car body, to achieve the maximum track width is an advantage. A wider track width makes the race car more stable, higher grip, with more corner speed & easier to drive.

G. With the lowest CG possible, the roll centers also need to be low. Ideally the front roll center is at 0" ground level in full dive at threshold braking. The rear roll center needs to be as low as is practical, while producing a roll axis that is optimum for the particular car to have neutral, balanced, high grip handling through all corners of the course.

H. Unsprung weight is everything not supported by the springs. In the front this includes half the control arms, tie rods & shocks & all of the tires, wheels, lugs, brake rotors, calipers, mounts, brake shrouds, uprights & hubs ... plus a portion of the brake cooling ducting. If we have IRS in the rear, the list is the same. If we run a straight axle rear, the list includes half the suspension links & shocks & all of the tires, wheels, lugs, brake rotors, caliper, mounts, brake shrouds, rear axle & hubs ... plus a portion of any brake cooling ducting.

Lighter unsprung weight allows the suspension to react & respond quicker to irregular track surface input, providing a higher % of loaded tire contact & grip. Lighter unsprung weight allows the suspension to react & respond quicker to Driver inputs & increases what the Driver feels in the race car.

I. Of the unsprung weight, the tires, wheels, lugs, brake rotors & hubs are ROTATING WEIGHT. Reducing rotating mass is even more critical than reducing unsprung weight. Accelerating & decelerating a heavier rotating mass take much more time. Said another way, lightening the rotating mass makes the car accelerate & decelerate quicker, producing quicker lap times.

J. The design structure of every component affects how well that component handles the forces inflicted upon it. The challenge is building lightweight chassis & components without having failures, or reduction in grip due to flex.

K. The degree of chassis rigidity ... and where it is ... needs to be designed into the car from the start. If a race car chassis is too flexible, the race car will have less grip, be less responsive to tuning changes & have a wider tuning sweet spot. If a race car chassis is too rigid, the race car will have more grip, be more responsive to tuning changes & have a narrower tuning sweet spot.

Race cars that are heavier, more powerful and/or capable of higher cornering g forces ... require more rigidity for optimum track performance. Race cars that are lighter, less powerful and/or capable of lower cornering g forces ... require less rigidity for optimum track performance.

L. Where the rigidity is designed into the chassis matters as well. Drag cars load the rear suspension significantly more than the front, so the rear of the chassis needs the majority of the chassis rigidity. Road race & oval tracks race cars load the front suspension significantly more than the rear, so the front of the chassis needs the majority of the chassis rigidity. Chassis rigidity designed into the car, needs to be tailored to the direction & location of forces seen dynamically.

M. Aero drag matters in road racing, but less than you may think. In high powered race cars on road courses, aero downforce is way more important than how much aero drag the race car has. The road race car that has more aero downforce, even with a bit more drag, will be the superior performer. With that said, we don't want unnecessary aero drag.

We want to eliminate & reduce all the aero drag possible, just not to the point of sacrificing aero downforce or track width. Yes, a wider track width & wider front end will create more frontal area & aero drag. The performance advantage of track width trumps aero drag on road courses.

The exception, to these aero rules, is super low powered cars where aero drag is more of a hinderance.

N. The suspension strategy that includes the target ride height, dive travel (under braking) & roll angle (when cornering) needs to be decided BEFORE the chassis & suspension are designed. There are a variety of reasons why, but the simple ones are ground clearance & camber gain.

If we design an optimal high travel suspension, for example 3"-4" of dive, we may utilize long control arms to slow the camber during dive. This way we can run optimal static camber & achieve the optimal camber gain. If we later decide to run a low travel suspension, for example 1"-1.5" of dive, the long control arms reduce the amount of camber gain can achieve. This problem would require us to run significantly more than optimal static camber, to arrive at the optimal camber. Conversely, we'll have the reverse problem if we start with a low travel design of shorter control arms & decide to run a high travel strategy ... too much camber gain.

On a different note, we may start with a low travel strategy, for example 1"-1.5" of dive, with a 2.5" ride height & later decide we want to run a high travel strategy, for example 3" of dive. The 2.5" ride height back at the firewall isn't the problem. The 2.25" height we designed the FACL crossmember on the front clip is the problem. If we knew we're going higher travel to start, we would raise the front clip (so to speak) in the design phase, so the FACL crossmember allows that travel.

O. Stiction & friction choices are not often thought about during the design process. But those decisions are often made during design & can be hard to change. Suspension bushings for example. If the chassis & control arms are designed for conventional wide bushings, deciding later to reduce stiction & friction with rod ends can be troublesome. Same with ball joints. Decide this early on.

P. Safety is often thought of as cage design, seat configuration, harnesses, suits, helmets, HANS & nets. These are all good to decide on beforehand as well, for increased protection in a crash. But spindle, hub & bearing failure cause more crashes than any other part on the car.

Race cars that are heavier, more powerful and/or capable of higher cornering g forces ... create higher load on the critical spindle, hub & bearing components. To PREVENT crashes in the first place, work out the load ratings of our spindle, hub & bearing with a safety factor built in.

20 CRITICAL HANDLING CONCEPTS:

1. A car with heavier front weight bias, can go no faster through a corner than the front tires can grip. Balancing the rear tire grip to the front ... for balanced neutral handling ... is relatively easy ... compared to the complexities of optimizing front tire grip.

2. What we do WITH & TO the TIRES ... are the key to performance. Contact patch is the highest priority, with how we load the tires a close second.

3. Geometry design, settings & changes to need to focus on how the tires contact the road dynamically & are loaded.

4. Tires are the only thing that connect the race car to the track surface. Tires play the largest role in race car performance. Rubber in tires hardens rapidly from the day they come out of the mold. Don't run old tires ... unless you want to learn how much it costs to repair race cars. The absolute best performance gain we can make to any race car is fresh, matched tires.

Matching the tires in rubber cure rate, durometer, sizing & sidewall spring rate is key to eliminating handling gremlins that make no sense. The grip level tires are capable of are based on these factors, regardless of tread depth! If the front and/or rear tires aren't matched, we will have different handling issues turning left & right.

5. After the car is built, tires are selected & the geometry is optimum ... most chassis fine tuning is to control the degree of load transfer to achieve the traction goal & handling balance. Dynamic force (load & load transfer) applied to a tire adds grip to that tire. With the exception of aerodynamics, load transfer from tire(s) to tire(s) is the primary force we have to work with.

6. The car's Center of Gravity (CG) acts as a lever on the Roll Center ... to load the tires ... separately front & rear. Higher CG's and/or lower RC's increases Roll Angle, but loads the tires more. Lower CG's and/or higher RC's decrease Roll Angle, but load the tires less. Getting the front & rear of the car to roll on an optimum roll axis is desired. Getting them to roll exactly the same is not the goal, because ...

7. Perpetual goal is to achieve maximum grip & neutral, balanced handling simultaneously through all the corners of the course. To do requires reducing the loading on the inside rear tire (to a degree) ... then increasing the loading of the inside rear tire (to a higher degree) for maximum forward bite on exit. So, on entry & mid-corner, the car needs to roll slightly less in the front to keep both front tires engaged for optimum front end grip, while allowing the car to roll slightly more in the rear to disengage the inside rear tire, to a small degree, to turn better.

For optimal corner exit, the car will have more roll in the front & less in the rear to re-engage the inside rear tire to a higher degree than it was on entry & exit, for maximum forward bite (traction) on exit. This difference is called diagonal roll. This amount differs as speeds & g-forces differ.

8. Modern day tuners do not use the RC height as the primary means of controlling Roll Angle. We use the suspension tuning items as our priority tools to control Roll Angle. We use the RC priority to load the tires optimally. So, to achieve the optimum balance of Roll Angle & working all four tires optimally ... this all has to work with our suspension ... springs, anti-roll bars & shocks ... and track width ... to end up at the optimum Roll Angle for our car & track application.

9. Sway Bars primarily control how far the front or rear suspension (and therefore chassis) "rolls" under force, and only secondarily influences the rate of roll. Softer bars allow increased Roll Angle & more load transfer from the inside tires to the outside tires. Stiffer bars reduce Roll Angle, keeping the car flatter & less load transfer from the inside tires to the outside tires.

10. Springs primarily control how far a suspension corner travels under force, and only secondarily influences the rate of travel. Shocks primarily control the rate of suspension corner travel under force, and only secondarily have influence on how far.

11. Springs, shocks & sway bars need to work together "as a team." Our springs' primary role is controlling dive & rise, also contribute significantly to the car's roll resistance. Our anti-roll bars (sway bars) primary role is controlling roll, but do contribute minutely to dive & rise. Our shocks primarily role is controlling the RATE of these changes, primarily during race car transitions from Driver input, such as braking throttle & steering. They all affect each other, but choose the right tool for the job & we create a harmonious team.

12. The front tires need force, from load transfer on corner entry, to provide front tire GRIP. Too little & the car pushes ... too much & the car is loose on entry. The rear tires need force, from load transfer on corner exit, to provide rear tire GRIP. Too little & the car is loose ... too much & the car pushes on exit.

13. Springs & Sway Bars are agents to load the tires with the force needed to produce maximum grip. Stiffer springs produce the needed force with less travel, whereas softer springs produce the needed force with more travel. Stiffer Sway Bars produce the needed force with less chassis roll, whereas softer Sway Bars produce the needed force with more chassis roll. The tire doesn't care which tool provides the loading force. Ultimately, they combine to produce a wheel load. Our role is to package the right combination for the target dive travel, chassis roll angle & wheel loading we need.

14. Softer front springs allow more compression travel in dive from braking & therefore a lower CG, more front grip & less rear grip. Stiffer front springs reduce compression travel in dive from braking & therefore a higher CG, less front grip & more rear grip. There are pros, cons & exceptions to these rules.

15. Too much Roll Angle overworks the outside tires in corners & underworks the inside tires. Too little Roll Angle underworks the outside tires in a corner. Excessive Roll Angle works the outside tires too much ... may provide an "ok" short run set-up ... but will be "knife edgy" to drive on long runs. The tires heat up quicker & go away quicker. If it has way too much Roll Angle ... the car loses grip as the inside tires are not being properly utilized.

16. Too little Roll Angle produces less than optimum grip. The car feels "skatey" to drive ... like it's "on top of the track." The outside tires are not getting worked enough, therefore not gripping enough. Tires heat up slower & car gets better very slowly over a long run as tires Gain heat.

17. A lower chassis Roll Angle works both sides of the car's tires "closer to even" ... within the optimum tire heat range ... providing a consistent long run set-up & optimum cornering traction, providing the fastest, most drivable race car.

18. Higher Roll Angles work better in tight corners but suffer in high speed corners. Lower Roll Angles work better in high speed corners but suffer in tight corners. The goal on a road course with various tight & high speed corners ... is to find the best balance & compromise that produces the quickest lap times. Smart Tuners use Roll Centers & Aero to achieve this.

19. Tuning is NOT linear two directions with stops at the ends. A car can be loose because it has too little Roll Angle in the rear & is not properly working the outside rear tire. A car can be loose because it has too much Roll Angle in the rear & is not properly working the inside rear tire.

A race car can be pushy because it has too little Roll Angle in the front & is not properly working the outside front tire. A race car can be pushy because it has too much Roll Angle in the front & is not properly working the inside front tire.

20. Don't forget the role & effects the engine, gears, brakes, Driver & track conditions each have on handling.

#62

Suspension Setup Strategies for Track & Racing / Suspension Setup Strategies

Last post by Ron Sutton - Dec 06, 2025, 06:43 PMSuspension Setup Strategies

Welcome,

I promise to post advice only when I have significant knowledge & experience on the topic. Please don't be offended if you ask me to speculate & I decline. I don't like to guess, wing it or BS on things I don't know. I figure you can wing it without my input, so no reason for me to wing it for you.

A few guidelines I'm asking for this thread:

1. I don't enjoy debating the merits of tuning strategies with anyone that thinks it should be set-up or tuned another way. It's not fun or valuable for me, so I simply don't do it. Please don't get mad if I won't debate with you.

2. If we see it different ... let's just agree to disagree & go run 'em on the track. Arguing on an internet forum just makes us all look stupid. Besides, that's why they make race tracks, have competitions & then declare winners & losers.

3. To my engineering friends ... I promise to use the wrong terms ... or the right terms the wrong way. Please don't have a cow.

4. To my car guy friends ... I promise to communicate as clear as I can in "car guy" terms. Some stuff is just complex or very involved. If I'm not clear ... call me on it.

5. I type so much, so fast, I often misspell or leave out words. Ignore the mistakes if it makes sense. But please bring it up if it doesn't.

6. I want people to ask questions. That's why I'm starting this thread ... so we can discuss & learn. There are no stupid questions, so please don't be embarrassed to ask about anything within the scope of the thread.

7. If I think your questions ... and the answers to them will be valuable to others ... I want to leave it on this thread for all of us to learn from. If your questions get too specific to your car only & I think the conversation won't be of value to others ... I may ask you to start a separate thread where you & I can discuss your car more in-depth.

8. Some people ask me things like "what should I do?" ... and I can't answer that. It's your hot rod. I can tell you what doing "X" or "Y" will do and you can decide what makes sense for you.

9. It's fun for me to share my knowledge & help people improve their cars. It's fun for me to learn stuff. Let's keep this thread fun.

10. As we go along, I may re-read what I wrote ... fix typos ... and occasionally, fix or improve how I stated something. When I do this, I will color that statement red, so it stands out if you re-skim this thread at some time too.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Let's Clarify the Cars We're Discussing:

We're going to keep the conversation to typical full bodied Track & Road Race cars ... front engine, rear wheel drive ... with a ride height requirement of at least 1.5" or higher. They can be tube chassis or oem bodied cars ... straight axle or IRS ... with or without aero ... and for any purpose that involves road courses or autocross.

But if the conversation bleeds over into other types of cars too much ... I may suggest we table that conversation. The reason is simple, setting up & tuning these different types of cars ... are well ... different. There are genres of race cars that have such different needs, they don't help the conversation here.

In fact, they cloud the issue many times. If I hear one more time how F1 does XYZ ... in a conversation about full bodied track/race cars with a X" of ride height ... I may shoot someone. Just kidding. I'll have it done. LOL

Singular purpose designed race cars like Formula 1-2-3-4, Formula Ford, F1600, F2000, etc, Indy Cars, IMSA Prototypes, Open Wheel Midgets & Sprint Cars. First, none of them have a body that originated as a production car. Second, they have no ride height rule, so they run almost on the ground & do not travel the suspension very far. Formula 1-2-3-4, Formula Ford, F1600, F2000, etc, Indy Cars, IMSA Prototypes are rear engine. The Open Wheel Midgets & Sprint Cars are front engine & run straight axles in front.

I have a lot of experience with these cars & their suspension & geometry needs are VERY different than full bodied track & road race cars with a significant ride height. All of them have around 60% rear weight bias. That changes the game completely. With these cars we're always hunting for more REAR grip, due to the around 60%+/- rear weight bias.

In all my full bodied track & road race cars experience ... Stock Cars, Road Race GT cars, TA/GT1, etc. ... with somewhere in the 50%-58% FRONT bias ... we know we can't go any faster through the corners than the front end has grip. So, what we need to do, compared to Formula 1-2-3-4, Formula Ford, F1600, F2000, etc, Indy Cars, IMSA Prototypes, Open Wheel Midgets & Sprint Cars, is very different.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Before we get started, let's get on the same page with terms & critical concepts.

Shorthand Acronyms

IFT = Inside Front Tire

IRT = Inside Rear Tire

OFT = Outside Front Tire

ORT = Outside Rear Tire

*Inside means the tire on the inside of the corner, regardless of corner direction.

Outside is the tire on the outside of the corner.

LF = Left Front

RF = Right Front

LR = Left Rear

RR = Right Rear

ARB = Anti-Roll Bar (Sway Bar)

FLLD = Front Lateral Load Distribution

RLLD = Rear Lateral Load Distribution

TRS = Total Roll Stiffness

LT = Load Transfer

RA = Roll Angle

RC = Roll Center

CG = Center of Gravity

CL = Centerline

FACL = Front Axle Centerline

RACL = Rear Axle Centerline

UCA = Upper Control Arm

LCA = Lower Control Arm

LBJ = Lower Ball Joint

UBJ = Upper Ball Joint

BJC = Ball Joint Center

IC = Instant Center is the pivot point of a suspension assembly or "Swing Arm"

CL-CL = Distance from centerline of one object to the centerline of the other

KPI = King Pin Inclination, an older term for the angle of the ball joints in relation to the spindle

SAI = Steering Angle Inclination, a modern term for the angle of the ball joints in relation to the spindle

TERMS:

Roll Centers = Cars have two Roll Centers ... one as part of the front suspension & one as part of the rear suspension, that act as pivot points. When the car experiences body roll during cornering ... everything above that pivot point rotates towards the outside of the corner ... and everything below the pivot point rotates the opposite direction, towards the inside of the corner.

Center of Gravity = Calculation of the car's mass to determine where the center is in all 3 planes. When a car is cornering ... the forces that act on the car to make it roll ... act upon the car's Center of Gravity (CG). With typical production cars & "most" race cars, the CG is above the Roll Center ... acting like a lever. The distance between the height of the CG & the height of each Roll Center is called the "Moment Arm." Think of it a lever. The farther apart the CG & Roll Center are ... the more leverage the CG has over the Roll Center to make the car roll.

Instant Center is the point where a real pivot point is, or two theoretical suspension lines come together, creating a pivot arc or swing arm.

Swing Arm is the length of the theoretical arc of a suspension assembly, created by the Instant Center.

Static Camber is the tire angle (as viewed from the front) as the car sits at ride height. Straight up, 90 degrees to the road would be zero Camber. Positive Camber would have the top of tire leaned outward, away from the car. Negative Camber would have the top of tire leaned inward, towards the center of the car.

Camber Gain specifically refers to increasing negative Camber (top of wheel & tire leaning inward, towards the center of the car) as the suspension compresses under braking & cornering.

Total Camber is the combination of Static Camber & Camber Gain ... under braking, in dive with no roll & no steering, as well as the Dynamic Camber with chassis roll & steering.

Dynamic Camber refers to actual angle of the wheel & tire (top relative to bottom) ... compared to the track surface ... whit the suspension in dive, with full chassis roll & a measure of steering. In others, dynamically in the corner entry. For our purposes, we are assuming the car is being driven hard, at its limits, so the suspension compression & chassis/body roll are at their maximum.

Static Caster is the spindle angle (viewed from the side with the wheel off). Straight up, 90 degrees to the road would be zero Caster. Positive Caster would have the top of spindle leaned back toward to cockpit. Negative Caster would have the top of spindle leaned forward towards the front bumper.

Caster Gain is when the Caster angle of the spindle increases (to the positive) as the suspension is compressed, by the upper ball joint migrating backwards and/or the lower ball joint migrating forward ... as the control arms pivot up. This happens when the upper and/or lower control arms are mounted to create Anti-dive. If there is no Anti-dive, there is no Caster Gain. If there is Pro-Dive, there is actually Caster loss.

Anti-Dive is the mechanical leverage to resist or slow compression of the front suspension (to a degree) under braking forces. Anti-dive can be achieved by mounting the upper control arms higher in the front & lower in the rear creating an angled travel. Anti-dive can also be achieved by mounting the lower control arms lower in the front & higher in the rear, creating an angled travel. If both upper & lower control arms were level & parallel, the car would have zero Anti-dive.

Pro-Dive is the opposite of Anti-dive. It is the mechanical leverage to assist or speed up compression of the front suspension (to a degree) under braking forces. Provide is achieved by mounting the upper control arms lower in the front & higher in the rear, creating the opposite angled travel as Anti-Dive. Pro-dive can also be achieved by mounting the lower control arms higher in the front & lower in the rear, creating the opposite angled travel as Anti-Dive.

Split is the measurement difference in two related items. We would say the panhard bar has a 1" split if one side was 10" & the other side 11". If we had 1° of Pro-Dive on one control arm & 2° of Anti-Dive on the other, we would call that a 3° split. If we have 8° of Caster on one side & 8.75° on the other, that is a .75° split.

Scrub Radius = A car's Scrub Radius is the distance from the steering axis line to tread centerline at ground level. It starts by drawing a line through our upper & lower ball joints, to the ground, that is our car's steering axis line. The dimension, at ground level, to the tire tread centerline, is the Scrub Radius. The tire's contact patch farthest from the steering axis loses grip earliest & most during steering. This reduces the tire's grip on tight corners. The largest the Scrub Radius, the more pronounced the loss of grip is on tight corners. Reducing the Scrub Radius during design increases front tire grip on tight corners.

Baseline Target is the package of information about the car, like ride height, dive travel, Roll Angle, CG height, weight, weight bias, tires & wheel specifications, track width, engine power level, estimated downforce, estimated max corner g-force, etc. We call it "Baseline" ... because it's where we're starting at & "Target" because these key points are the targets we're aiming to achieve. We need to work this package of information prior to chassis & suspension design, or we have no target.

Total Roll Stiffness (aka TRS) is the mathematical calculation of the "roll resistance" built into the car with springs, Sway Bars, Track Width & Roll Centers. Stiffer springs, bigger Sway Bars, higher Roll Centers & wider Track Widths make this number go UP & the Roll Angle of the car to be less. "Total Roll Stiffness" is expressed in foot-pounds per degree of Roll Angle ... and it does guide us on how much the car will roll.

Front Lateral Load Distribution & Rear Lateral Load Distribution (aka FLLD & RLLD):

FLLD/RLLD are stated in percentages, not pounds. The two always add up to 100% as they are comparing front to rear roll resistance split. Knowing the percentages alone, will not provide clarity as to how much the car will roll ... just how the front & rear roll in comparison to each other. If the FLLD % is higher than the RLLD % ... that means the front suspension has a higher resistance to roll than the rear suspension ... and therefore the front of the car runs flatter than the rear of the suspension ... which is the goal.

Roll is the car chassis and body "rolling" on its Roll Axis (side-to-side) in cornering.

Roll Angle is the amount the car "rolls" on its Roll Axis (side-to-side) in cornering, usually expressed in degrees.

Dive is the front suspension compressing under braking forces.

Full Dive is the front suspension compressing to a preset travel target, typically under threshold braking. It is NOT how far it can compress.

Rise = Can refer to either end of the car rising up.

Squat = Refers to the car planting the rear end on launch or under acceleration.

Pitch = Fore & aft body rotation. As when the front end dives & back end rises under braking or when the front end rises & the back end squats under acceleration.

Pitch Angle is the amount the car "rotates" fore & aft under braking or acceleration, usually expressed by engineers in degrees & in inches of rise or dive by Racers.

Diagonal Roll is the combination of pitch & roll. It is a dynamic condition. On corner entry, when the Driver is both braking & turning, front is in dive, the rear may, or may not, have rise & the body/chassis are rolled to the outside of the corner. In this dynamic state the outside front of the car is lowest point & the inside rear of the car is the highest point.

Track Width is the measurement center to center of the tires' tread, measuring both front or rear tires.

Tread Width is the measurement outside to outside of the tires' tread. (Not sidewall to sidewall)

Tire Width is the measurement outside to outside of the sidewalls. A lot of people get these confused & our conversations get sidelined.

Floating typically means one component is re-engineered into two components that connect, but mount separate. In rear ends, a "Floater" has hubs that mount & ride on the axle tube ends, but is separate from the axle itself. They connect via couplers. In brakes, a floating caliper or rotor means it is attached in a way it can still move to some degree.

Decoupled typically means one component is re-engineered into two components that connect, but ACT separately. In suspensions, it typically means one of the two new components perform one function, while the second component performs a different function.

Spring Rate = Pounds of linear force to compress the spring 1". If a spring is rated at 500# ... it takes 500# to compress it 1"

Spring Force = Total amount of force (weight and/or load transfer) on the spring. If that same 500# spring was compressed 1.5" it would have 750# of force on it.

Sway Bar, Anti-Sway Bar, Anti Roll Bar = All mean the same thing. Kind of like "slim chance" & "fat chance."

Sway Bar Rate = Pounds of torsional force to twist the Sway Bar 1 inch at the link mount on the control arm.

Rate = The rating of a device often expressed in pounds vs distance. A 450# spring takes 900# to compress 2".

Rate = The speed at which something happens, often expressed in time vs distance. 3" per second. 85 mph. * Yup, dual meanings.

Corner Weight = What each, or a particular, corner of the race car weighs when we scale the car with 4 scales. One under each tire.

Weight Bias = Typically compares the front & rear weight bias of the race car on scales. If the front of the car weighs 1650# & the rear weighs 1350# (3000# total) we would say the car has a 55%/45% front bias. Bias can also apply to side to side weights, but not cross weight. If the left side of the car weighs 1560# & the right 1440#, we would say the car has a 52/42 left side bias.

Cross Weight = Sometimes called "cross" for short or wedge in oval track racing. This refers to the comparison of the RF & LR corner weights to the LF & RR corner weights. If the RF & LR corner scale numbers add up to the same as the LF & RR corners, we would say the car has a 50/50 cross weight. In oval track circles, they may say we have zero wedge in the car. If the RF & LR corner scale numbers add up to 1650# & the LF & RR corners add up to 1350#, we would say the car has a 55/45 cross weight. In oval track circles, they may say we have 5% wedge in the car, or refer to the total & say we have 55% wedge in the car.

Grip & Bite = Are my slang terms for tire traction.

Push = Oval track slang for understeer, meaning the front tires have lost grip and the car is going towards the outside of the corner nose first.

Loose = Oval track slang for oversteer meaning the rear tires have lost grip and the car is going towards the outside of the corner tail first.

Tight is the condition before push, when the steering wheel feels "heavy" ... is harder to turn ... but the front tires have not lost grip yet.

Free is the condition before loose, when the steering in the corner is easier because the car has "help" turning with the rear tires in a slight "glide" condition.

Good Grip is another term for "balanced" or "neutral" handling condition ... meaning both the front & rear tires have good traction, neither end is over powering the other & the car is turning well.

Mean = My slang term for a car that is bad fast, suspension is on kill, handling & grip turned up to 11, etc., etc.

Greedy is when we get too mean with something on the car, too aggressive in our setup & it causes problems.

Steering Turn-In is when the Driver initiates steering input turning into the corner.

Steering Unwind is when the Driver initiates steering input out of the corner.

Steering Set is when the Driver holds the steering steady during cornering. This is in between Steering Turn-In & Steering Unwind.

Roll Thru Zone = The section of a corner, typically prior to apex, where the Driver is off the brakes & throttle. The car is just rolling. The start of the Roll Thru Zone is when the Driver releases the brakes 100%. The end of the Roll Thru Zone is when the Driver starts throttle roll on.

TRO/Throttle Roll On is the process of the Driver rolling the throttle open at a controlled rate.

Trail Braking is the process of the Driver braking while turning into the corner. Typically, at the weight & size of the cars we're discussing here ... the Driver starts braking before Steering Turn-In ... and the braking after that is considered Trail Braking. This is the only fast strategy. Driver's that can't or won't trail brake are back markers.

Threshold Braking = The Driver braking as hard as possible without locking any tires, to slow the car as quickly as possible to the target speed for the Roll Thru Zone. Typically done with very late, deep braking to produce the quickest lap times.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

16 CRITICAL RACE CAR DESIGN CONCEPTS:

A. One of the most important design factors is utilizing all four tires on the track surface for maximum possible adhesion. Shaker Rigs (6, 7 & 8 post rigs) exist to help race car designers, teams & engineers maximize tire contact & loading to the track surface. As a general rule, anything that reduces contact patch and/or tire loading is our enemy & anything that increases contact patch (up to optimum) and/or achieves optimum loading of all four tires is our friend.

B. Weight is our enemy. Lighter race cars do everything better. They turn better. They accelerate better. They decelerate better. They even crash better (safer). They stress all the components less. Building a lighter car allows us to run less heavy duty, lighter suspension components reducing unsprung & rotating mass ... leading to an even lighter, faster race car. Every ounce matters if you are serious about winning.

C. Center of Gravity (aka CG ... aka weight mass) matters ... a lot. The mantra of oval track race car builders when it comes to race car weight is "low, light & left." (More left side weight helps cars turning left.) For road race cars it is "low, light & centered." The goal is to have the lightest race car ... weigh the exact same on all four scales ... with the majority of the mass (CG) low in the car & centered in the cockpit.

When the race series or class has a weight minimum, the Racers that build the car as light as practical, then places weight (lead, steel, tungsten) near the center of the car, down low ... will produce a faster, better handling, safer race car.

D. When we design a race car with a lower center of gravity, it is much easier to drive & can be much faster. A lower center of gravity allows the race car to run flatter through the corners, working all four tires better ... more grip ... more corner speed. A lower center of gravity allows the race car to pitch less (dive & rise) under braking & acceleration, working all four tires better ... more grip ... more corner entry & exit speed. A lower center of gravity makes the race car more stable, higher grip & easier to drive.

E. If we carelessly design a race car with excessive weight (mass) outside the axle centerlines, we're asking for a scary, ill handling, even dangerous handling, race car. Excess weight ahead of the front axle centerline will make the front end of the car swing out when we exceed total tire grip. Big push (understeer) & then nose hard into the outside barrier.

Similar in the rear. Excess weight behind of the rear axle centerline will make the rear end of the car swing out when we exceed total tire grip. Hard loose condition (oversteer) & then back hard into the outside barrier. Designing the race car with as much of its needed mass inside the axle centerlines is critical.

F. Track width is CRITICAL. Racing sanctioning bodies know this & enforce track width rules diligently, because all knowledgeable Racers know that even a small increase in track width can provide a significant advantage. Very similar to having a lower center of gravity ... having a wider track width allows the race car to run flatter through the corners, working all four tires better ... more grip ... more corner speed. A wider track width makes the race car more stable, higher grip & easier to drive.

With exception for tight, narrow autocross courses, designing the race car with the widest track width possible is the goal. Widening the car body, or building a wider car body, to achieve the maximum track width is an advantage. A wider track width makes the race car more stable, higher grip, with more corner speed & easier to drive.

G. With the lowest CG possible, the roll centers also need to be low. Ideally the front roll center is at 0" ground level in full dive at threshold braking. The rear roll center needs to be as low as is practical, while producing a roll axis that is optimum for the particular car to have neutral, balanced, high grip handling through all corners of the course.

H. Unsprung weight is everything not supported by the springs. In the front this includes half the control arms, tie rods & shocks & all of the tires, wheels, lugs, brake rotors, calipers, mounts, brake shrouds, uprights & hubs ... plus a portion of the brake cooling ducting. If we have IRS in the rear, the list is the same. If we run a straight axle rear, the list includes half the suspension links & shocks & all of the tires, wheels, lugs, brake rotors, caliper, mounts, brake shrouds, rear axle & hubs ... plus a portion of any brake cooling ducting.

Lighter unsprung weight allows the suspension to react & respond quicker to irregular track surface input, providing a higher % of loaded tire contact & grip. Lighter unsprung weight allows the suspension to react & respond quicker to Driver inputs & increases what the Driver feels in the race car.

I. Of the unsprung weight, the tires, wheels, lugs, brake rotors & hubs are ROTATING WEIGHT. Reducing rotating mass is even more critical than reducing unsprung weight. Accelerating & decelerating a heavier rotating mass take much more time. Said another way, lightening the rotating mass makes the car accelerate & decelerate quicker, producing quicker lap times.

J. The design structure of every component affects how well that component handles the forces inflicted upon it. The challenge is building lightweight chassis & components without having failures, or reduction in grip due to flex.

K. The degree of chassis rigidity ... and where it is ... needs to be designed into the car from the start. If a race car chassis is too flexible, the race car will have less grip, be less responsive to tuning changes & have a wider tuning sweet spot. If a race car chassis is too rigid, the race car will have more grip, be more responsive to tuning changes & have a narrower tuning sweet spot.

Race cars that are heavier, more powerful and/or capable of higher cornering g forces ... require more rigidity for optimum track performance. Race cars that are lighter, less powerful and/or capable of lower cornering g forces ... require less rigidity for optimum track performance.

L. Where the rigidity is designed into the chassis matters as well. Drag cars load the rear suspension significantly more than the front, so the rear of the chassis needs the majority of the chassis rigidity. Road race & oval tracks race cars load the front suspension significantly more than the rear, so the front of the chassis needs the majority of the chassis rigidity. Chassis rigidity designed into the car, needs to be tailored to the direction & location of forces seen dynamically.

M. Aero drag matters in road racing, but less than you may think. In high powered race cars on road courses, aero downforce is way more important than how much aero drag the race car has. The road race car that has more aero downforce, even with a bit more drag, will be the superior performer. With that said, we don't want unnecessary aero drag.

We want to eliminate & reduce all the aero drag possible, just not to the point of sacrificing aero downforce or track width. Yes, a wider track width & wider front end will create more frontal area & aero drag. The performance advantage of track width trumps aero drag on road courses.

The exception, to these aero rules, is super low powered cars where aero drag is more of a hinderance.

N. The suspension strategy that includes the target ride height, dive travel (under braking) & roll angle (when cornering) needs to be decided BEFORE the chassis & suspension are designed. There are a variety of reasons why, but the simple ones are ground clearance & camber gain.

If we design an optimal high travel suspension, for example 3"-4" of dive, we may utilize long control arms to slow the camber during dive. This way we can run optimal static camber & achieve the optimal camber gain. If we later decide to run a low travel suspension, for example 1"-1.5" of dive, the long control arms reduce the amount of camber gain can achieve. This problem would require us to run significantly more than optimal static camber, to arrive at the optimal camber. Conversely, we'll have the reverse problem if we start with a low travel design of shorter control arms & decide to run a high travel strategy ... too much camber gain.

On a different note, we may start with a low travel strategy, for example 1"-1.5" of dive, with a 2.5" ride height & later decide we want to run a high travel strategy, for example 3" of dive. The 2.5" ride height back at the firewall isn't the problem. The 2.25" height we designed the FACL crossmember on the front clip is the problem. If we knew we're going higher travel to start, we would raise the front clip (so to speak) in the design phase, so the FACL crossmember allows that travel.

O. Stiction & friction choices are not often thought about during the design process. But those decisions are often made during design & can be hard to change. Suspension bushings for example. If the chassis & control arms are designed for conventional wide bushings, deciding later to reduce stiction & friction with rod ends can be troublesome. Same with ball joints. Decide this early on.

P. Safety is often thought of as cage design, seat configuration, harnesses, suits, helmets, HANS & nets. These are all good to decide on beforehand as well, for increased protection in a crash. But spindle, hub & bearing failure cause more crashes than any other part on the car.

Race cars that are heavier, more powerful and/or capable of higher cornering g forces ... create higher load on the critical spindle, hub & bearing components. To PREVENT crashes in the first place, work out the load ratings of our spindle, hub & bearing with a safety factor built in.

20 CRITICAL HANDLING CONCEPTS:

1. A car with heavier front weight bias, can go no faster through a corner than the front tires can grip. Balancing the rear tire grip to the front ... for balanced neutral handling ... is relatively easy ... compared to the complexities of optimizing front tire grip.

2. What we do WITH & TO the TIRES ... are the key to performance. Contact patch is the highest priority, with how we load the tires a close second.

3. Geometry design, settings & changes to need to focus on how the tires contact the road dynamically & are loaded.

4. Tires are the only thing that connect the race car to the track surface. Tires play the largest role in race car performance. Rubber in tires hardens rapidly from the day they come out of the mold. Don't run old tires ... unless you want to learn how much it costs to repair race cars. The absolute best performance gain we can make to any race car is fresh, matched tires.

Matching the tires in rubber cure rate, durometer, sizing & sidewall spring rate is key to eliminating handling gremlins that make no sense. The grip level tires are capable of are based on these factors, regardless of tread depth! If the front and/or rear tires aren't matched, we will have different handling issues turning left & right.

5. After the car is built, tires are selected & the geometry is optimum ... most chassis fine tuning is to control the degree of load transfer to achieve the traction goal & handling balance. Dynamic force (load & load transfer) applied to a tire adds grip to that tire. With the exception of aerodynamics, load transfer from tire(s) to tire(s) is the primary force we have to work with.

6. The car's Center of Gravity (CG) acts as a lever on the Roll Center ... to load the tires ... separately front & rear. Higher CG's and/or lower RC's increases Roll Angle, but loads the tires more. Lower CG's and/or higher RC's decrease Roll Angle, but load the tires less. Getting the front & rear of the car to roll on an optimum roll axis is desired. Getting them to roll exactly the same is not the goal, because ...

7. Perpetual goal is to achieve maximum grip & neutral, balanced handling simultaneously through all the corners of the course. To do requires reducing the loading on the inside rear tire (to a degree) ... then increasing the loading of the inside rear tire (to a higher degree) for maximum forward bite on exit. So, on entry & mid-corner, the car needs to roll slightly less in the front to keep both front tires engaged for optimum front end grip, while allowing the car to roll slightly more in the rear to disengage the inside rear tire, to a small degree, to turn better.

For optimal corner exit, the car will have more roll in the front & less in the rear to re-engage the inside rear tire to a higher degree than it was on entry & exit, for maximum forward bite (traction) on exit. This difference is called diagonal roll. This amount differs as speeds & g-forces differ.

8. Modern day tuners do not use the RC height as the primary means of controlling Roll Angle. We use the suspension tuning items as our priority tools to control Roll Angle. We use the RC priority to load the tires optimally. So, to achieve the optimum balance of Roll Angle & working all four tires optimally ... this all has to work with our suspension ... springs, anti-roll bars & shocks ... and track width ... to end up at the optimum Roll Angle for our car & track application.

9. Sway Bars primarily control how far the front or rear suspension (and therefore chassis) "rolls" under force, and only secondarily influences the rate of roll. Softer bars allow increased Roll Angle & more load transfer from the inside tires to the outside tires. Stiffer bars reduce Roll Angle, keeping the car flatter & less load transfer from the inside tires to the outside tires.[/color]

10. Springs primarily control how far a suspension corner travels under force, and only secondarily influences the rate of travel. Shocks primarily control the rate of suspension corner travel under force, and only secondarily have influence on how far.

11. Springs, shocks & sway bars need to work together "as a team." Our springs' primary role is controlling dive & rise, also contribute significantly to the car's roll resistance. Our anti-roll bars (sway bars) primary role is controlling roll, but do contribute minutely to dive & rise. Our shocks primarily role is controlling the RATE of these changes, primarily during race car transitions from Driver input, such as braking throttle & steering. They all affect each other, but choose the right tool for the job & we create a harmonious team.

12. The front tires need force, from load transfer on corner entry, to provide front tire GRIP. Too little & the car pushes ... too much & the car is loose on entry. The rear tires need force, from load transfer on corner exit, to provide rear tire GRIP. Too little & the car is loose ... too much & the car pushes on exit.

13. Springs & Sway Bars are agents to load the tires with the force needed to produce maximum grip. Stiffer springs produce the needed force with less travel, whereas softer springs produce the needed force with more travel. Stiffer Sway Bars produce the needed force with less chassis roll, whereas softer Sway Bars produce the needed force with more chassis roll. The tire doesn't care which tool provides the loading force. Ultimately, they combine to produce a wheel load. Our role is to package the right combination for the target dive travel, chassis roll angle & wheel loading we need.

14. Softer front springs allow more compression travel in dive from braking & therefore a lower CG, more front grip & less rear grip. Stiffer front springs reduce compression travel in dive from braking & therefore a higher CG, less front grip & more rear grip. There are pros, cons & exceptions to these rules.

15. Too much Roll Angle overworks the outside tires in corners & underworks the inside tires. Too little Roll Angle underworks the outside tires in a corner. Excessive Roll Angle works the outside tires too much ... may provide an "ok" short run set-up ... but will be "knife edgy" to drive on long runs. The tires heat up quicker & go away quicker. If it has way too much Roll Angle ... the car loses grip as the inside tires are not being properly utilized.

16. Too little Roll Angle produces less than optimum grip. The car feels "skatey" to drive ... like it's "on top of the track." The outside tires are not getting worked enough, therefore not gripping enough. Tires heat up slower & car gets better very slowly over a long run as tires Gain heat.

17. A lower chassis Roll Angle works both sides of the car's tires "closer to even" ... within the optimum tire heat range ... providing a consistent long run set-up & optimum cornering traction, providing the fastest, most drivable race car.

18. Higher Roll Angles work better in tight corners but suffer in high speed corners. Lower Roll Angles work better in high speed corners but suffer in tight corners. The goal on a road course with various tight & high speed corners ... is to find the best balance & compromise that produces the quickest lap times. Smart Tuners use Roll Centers & Aero to achieve this.

19. Tuning is NOT linear two directions with stops at the ends. A car can be loose because it has too little Roll Angle in the rear & is not properly working the outside rear tire. A car can be loose because it has too much Roll Angle in the rear & is not properly working the inside rear tire.

A race car can be pushy because it has too little Roll Angle in the front & is not properly working the outside front tire. A race car can be pushy because it has too much Roll Angle in the front & is not properly working the inside front tire.

20. Don't forget the role & effects the engine, gears, brakes, Driver & track conditions each have on handling.

#63

Methods & Strategies to Increase Overall Grip for Track & Racing / Methods & Strategies to Increa...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Dec 06, 2025, 06:40 PMMethods & Strategies to Increase Overall Grip

Welcome,

I promise to post advice only when I have significant knowledge & experience on the topic. Please don't be offended if you ask me to speculate & I decline. I don't like to guess, wing it or BS on things I don't know. I figure you can wing it without my input, so no reason for me to wing it for you.

A few guidelines I'm asking for this thread:

1. I don't enjoy debating the merits of tuning strategies with anyone that thinks it should be set-up or tuned another way. It's not fun or valuable for me, so I simply don't do it. Please don't get mad if I won't debate with you.

2. If we see it different ... let's just agree to disagree & go run 'em on the track. Arguing on an internet forum just makes us all look stupid. Besides, that's why they make race tracks, have competitions & then declare winners & losers.

3. To my engineering friends ... I promise to use the wrong terms ... or the right terms the wrong way. Please don't have a cow.

4. To my car guy friends ... I promise to communicate as clear as I can in "car guy" terms. Some stuff is just complex or very involved. If I'm not clear ... call me on it.

5. I type so much, so fast, I often misspell or leave out words. Ignore the mistakes if it makes sense. But please bring it up if it doesn't.

6. I want people to ask questions. That's why I'm starting this thread ... so we can discuss & learn. There are no stupid questions, so please don't be embarrassed to ask about anything within the scope of the thread.

7. If I think your questions ... and the answers to them will be valuable to others ... I want to leave it on this thread for all of us to learn from. If your questions get too specific to your car only & I think the conversation won't be of value to others ... I may ask you to start a separate thread where you & I can discuss your car more in-depth.

8. Some people ask me things like "what should I do?" ... and I can't answer that. It's your hot rod. I can tell you what doing "X" or "Y" will do and you can decide what makes sense for you.

9. It's fun for me to share my knowledge & help people improve their cars. It's fun for me to learn stuff. Let's keep this thread fun.

10. As we go along, I may re-read what I wrote ... fix typos ... and occasionally, fix or improve how I stated something. When I do this, I will color that statement red, so it stands out if you re-skim this thread at some time too.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Let's Clarify the Cars We're Discussing:

We're going to keep the conversation to typical full bodied Track & Road Race cars ... front engine, rear wheel drive ... with a ride height requirement of at least 1.5" or higher. They can be tube chassis or oem bodied cars ... straight axle or IRS ... with or without aero ... and for any purpose that involves road courses or autocross.

But if the conversation bleeds over into other types of cars too much ... I may suggest we table that conversation. The reason is simple, setting up & tuning these different types of cars ... are well ... different. There are genres of race cars that have such different needs, they don't help the conversation here.

In fact, they cloud the issue many times. If I hear one more time how F1 does XYZ ... in a conversation about full bodied track/race cars with a X" of ride height ... I may shoot someone. Just kidding. I'll have it done. LOL