Recent posts

#11

Client Projects & Tips – Muscle Cars / 93 Mustang

Last post by Rob Tarrien - Jan 25, 2026, 12:43 PMI own this car since new. Was my daily for the first year and then the transformation started. I ordered this as a GT because the dealer weren't allowing Ford A plan pricing on the Cobra. The only thing I liked about the Cobra was the ground effects over the GT. I had a buddy that work at a Ford dealership and I ordered all the original Cobra ground effects for $1800. At the time Ford had released the Cobra R so I purchased the Cobra R double adjustable Koni's and added matching springs and swaybars. I added Baer Racings first brake kit which was C4 Corvette parts. I purchased a set of wheels from Baer in 17x9.

#12

Motorsports Events / NASA Race @ Sebring April 2-5

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 22, 2026, 04:19 PMI'll be at the NASA race in Sebring April 2nd through April 5th.

Sebring International Raceway Info HERE

NASA Race Weekend info HERE

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I have a whole catalog of Track-Warrior chassis packages that fit into the NASA Super racing classes. As well as Race-Pro & Race-Star "Race Car in a Box" for GM & Ford Muscle Cars to race in NASA's American Iron & American Iron Extreme classes. So I'll be shaking hands & hanging out with friends in the pits. If you see me in my typical black logo'd shirt, stop & say "howdy."

Sebring International Raceway Info HERE

NASA Race Weekend info HERE

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I have a whole catalog of Track-Warrior chassis packages that fit into the NASA Super racing classes. As well as Race-Pro & Race-Star "Race Car in a Box" for GM & Ford Muscle Cars to race in NASA's American Iron & American Iron Extreme classes. So I'll be shaking hands & hanging out with friends in the pits. If you see me in my typical black logo'd shirt, stop & say "howdy."

#13

Motorsports Events / Opening NASCAR Race @ Daytona

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 22, 2026, 04:13 PMI'll be in the pits at the NASCAR race in Daytona, February 13th & 14th.

I'll be with Bill McAnally Racing in the Truck Series Friday & Richard Childress Racing in the O'Reilly Series Saturday. I won't be there Sunday.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you see me in my typical black logo'd shirt, stop & say "howdy."

I'll be with Bill McAnally Racing in the Truck Series Friday & Richard Childress Racing in the O'Reilly Series Saturday. I won't be there Sunday.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you see me in my typical black logo'd shirt, stop & say "howdy."

#14

In Shop - Race Car Setup, Scaling & Alignment / Re: In Shop - Race Car Setup, ...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 22, 2026, 04:02 PMScaling a Car for Autocross, Track or Road Racing

To get this right, it's a process. Be patient, thorough & accurate. Let's start with getting the scales level & located properly to achieve accurate numbers. I use a what is called a scale platen to roll the cars on that has been leveled in every direction & locked down. Most guys don't have access to something like this, so let's talk about how to properly scale a car on the garage floor.

Tip #1: Take your time & get this right. The info that comes out of this is only as good as the accuracy of the scaling.

Tip #2: Yes, 1/8" is a big deal. I've seen garage floors off 1/2".

Getting the scales ready ...

a. Find spots on the garage floor to match the track width & wheel base of the car. Place the scales in a rectangle on the floor, dead center & square to those measurements.

Using a laser pointer or long, straight, non-bowed, stiff piece of tubing, make sure the scale pads are square to each other. Use blue masking tape to outline the four sides of the scales ... in the exact location they need to be on the floor. Now, during the process, when you knock scales around, you can always go right back to the correct spots.

b. All 4 scale pads need to be at the exact same height.

Using a laser level or long, straight, non-bowed, stiff piece of tubing & a level (digital is preferred as it will be more accurate) ... determine which pad is highest. Then using 16"x16" vinyl floor tile squares (Home Depot?) ... and thin pieces of 16"x16" sheet metal of different thicknesses ... shim the low pads to match the height of the tallest pad.

c. You want the pads themselves to be level too. So if the floor dips so much it causes a scale pad to sit at an angle, you may want to pick another spot, or put shims under the low end.

You want to end up with the scales:

* Centered for track width & wheelbase

* Level & level to each other

* Square to each other & outlined with tape

Grease Plates:

Anytime you jack & lower the front suspension, the tires will "bind" from rubber friction on the scales. This will sometime move the scales ... sometimes not. But it will always give you false ride height & scale numbers. So you need to prevent this "tire bind."

Make four square pieces of thin sheet metal somewhere around 12"x12" to 15"x15". I use .040" thick aluminum, because we have it around the shop often. Put a fine, thin, even film of grease on one side of two plates. Lay another plate on top of the greased up plates ... and you have two sets of "grease plates."

Lay these centered on top of the scales for the front tires. Now you can move the scales (shims & all) out of the way ... roll the car into place so the tires are centered in the tape squares ... jack one side (or one end) of the car up & place the scales in their tape boxes ... repeat on the other side (or other end).

In the real world, the car never ends up centered and the scales and/or grease plates are out of their boxes. Jack & move stuff until the scales are in their boxes & all four tires are centered on the scales & grease plates.

Prepping the car:

a. Put the fuel level in it you plan to compete with.

b. Air the tires up to the pressure you plan to compete with, or at least the same.

c. Put weight in the driver seat to match the driver's weight with helmet & gear.

d. Make sure the tires are dead true straight ahead. If you have toe-out, make sure both are evenly toed out.

e. For now ... unbolt one side of the sway bar linkage, on both front & rear bars, so they don't affect our numbers.

f. Mark a spot on the frame at all 4 corners where you will measure ride height ... and measure ride height before you start. Write them down.

Now, you can read the scales & see where you are. Write these numbers down, before you start making adjustments. I suggest you write down all your ride heights, adjustments & scale readings (with dates) from those changes and keep in a file folder. You'll need the info someday.

Ok ... before we make any adjustments ... is the car level side to side? If not, we need to fix this & the weights together. Never tweak on the adjusters to "hit a scale #" without keeping the ride heights correct. I prefer to get the ride heights even side to side ... and the desired rake front to rear ... then tune on the adjusters to achieve my scale numbers.

Here's how ...assuming your ride heights are even side to side:

• If you need to add cross weight (make the LR & RF heavier) adjust the spring adjusters to raise the LR & RF ... and to lower the RR & LF ... by the same amounts.

• In other words if you turned the spring adjusters to raise the LR & RF by 1 full turn ... turn the spring adjusters to lower the RR & LF by same 1 full turn.

• This will keep the ride heights "pretty close".

• When you get down to the gnat's eye, you'll need to tweak them individually ... but not by much.

• We almost always keep the ride heights level side to side for road course & autocross competition. There are exceptions, but not worth discussing here.

We only care about the numbers with the driver ... unless it's going to be a drone.

So for discussion sake, let's say the scales read

LF 1075# RF 1025#

LR 900# RR 900#

Results:

3900# Total weight

53.85% Front Weight Bias

50.64% Left Side Weight Bias

49.36% Cross weight or "wedge"

* As a "standard" tuners add up the weights of the LR & RF for a percentage.

This is where tuners differ. Some will adjust the spring adjusters to achieve 50.0% cross weight.

That would look like this:

LF 1062# RF 1038#

LR 913# RR 887#

* Remember, check your corner ride heights.

Results:

3900# Total weight

53.85% Front Weight Bias

50.64% Left Side Weight Bias

50.00% Cross weight or "wedge"

The problem with this strategy is the heavier left side weight will make the car roll less & have more grip on left hand corners ... and roll more & have less grip on right hand corners. An ideal solution would be to physically move weight from the left side of the car to the right side of the car.

Because ultimately an autocross, track car or road race car will perform best if the side-to-side weight bias is 50/50 ... and the cross weight is 50/50. But for many street cars, that is not practical. The best "compromise" solution that will produce the best handling (if the left side is heavier) is to run less cross weight than 50%.

I'd love to tell you the formula is XYZ. But in reality, every car is a bit different. I do however have a proven rule of thumb. And that is the cross weight & left side weight need to add up to 100.0%. So if the car's left side weight (with driver) is 50.6% ... then we need to reduce the cross weight from 50.0% to 49.%.

Hey wait a minute ... that's where we started in this example. Yup ... the 50.6% Left Side Weight Bias & 49.4% Cross weight kind of balance each other out. It's just an experienced starting point. Because you have other factors in your car that may make it have more grip one direction & less grip the other.

So driving it hard in autocross, track or road race competition & tuning it are what I suggest to achieve optimum balance for your car. More cross weight (heavier loaded LR & RF) will add grip turning left & free the car turning right. Less cross weight (heavier loaded RR & LF) will add grip turning right & free the car turning left.

You ... and everyone with adjustable spring heights ... have the ability to fine tune this and achieve the best balance.

Future posts will go over more detail.

#15

In Shop - Race Car Setup, Scaling & Alignment / In Shop - Race Car Setup, Scal...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 22, 2026, 03:57 PMIn Shop - Race Car Setup, Scaling & Alignment

Welcome,

I promise to post advice only when I have significant knowledge & experience on the topic. Please don't be offended if you ask me to speculate & I decline. I don't like to guess, wing it or BS on things I don't know. I figure you can wing it without my input, so no reason for me to wing it for you.

A few guidelines I'm asking for this thread:

1. I don't enjoy debating the merits of tuning strategies with anyone that thinks it should be set-up or tuned another way. It's not fun or valuable for me, so I simply don't do it. Please don't get mad if I won't debate with you.

2. If we see it different ... let's just agree to disagree & go run 'em on the track. Arguing on an internet forum just makes us all look stupid. Besides, that's why they make race tracks, have competitions & then declare winners & losers.

3. To my engineering friends ... I promise to use the wrong terms ... or the right terms the wrong way. Please don't have a cow.

4. To my car guy friends ... I promise to communicate as clear as I can in "car guy" terms. Some stuff is just complex or very involved. If I'm not clear ... call me on it.

5. I type so much, so fast, I often misspell or leave out words. Ignore the mistakes if it makes sense. But please bring it up if it doesn't.

6. I want people to ask questions. That's why I'm starting this thread ... so we can discuss & learn. There are no stupid questions, so please don't be embarrassed to ask about anything within the scope of the thread.

7. If I think your questions ... and the answers to them will be valuable to others ... I want to leave it on this thread for all of us to learn from. If your questions get too specific to your car only & I think the conversation won't be of value to others ... I may ask you to start a separate thread where you & I can discuss your car more in-depth.

8. Some people ask me things like "what should I do?" ... and I can't answer that. It's your hot rod. I can tell you what doing "X" or "Y" will do and you can decide what makes sense for you.

9. It's fun for me to share my knowledge & help people improve their cars. It's fun for me to learn stuff. Let's keep this thread fun.

10. As we go along, I may re-read what I wrote ... fix typos ... and occasionally, fix or improve how I stated something. When I do this, I will color that statement red, so it stands out if you re-skim this thread at some time too.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Let's Clarify the Cars We're Discussing:

We're going to keep the conversation to typical full bodied Track & Road Race cars ... front engine, rear wheel drive ... with a ride height requirement of at least 1.5" or higher. They can be tube chassis or oem bodied cars ... straight axle or IRS ... with or without aero ... and for any purpose that involves road courses or autocross.

But if the conversation bleeds over into other types of cars too much ... I may suggest we table that conversation. The reason is simple, setting up & tuning these different types of cars ... are well ... different. There are genres of race cars that have such different needs, they don't help the conversation here.

In fact, they cloud the issue many times. If I hear one more time how F1 does XYZ ... in a conversation about full bodied track/race cars with a X" of ride height ... I may shoot someone. Just kidding. I'll have it done. LOL

Singular purpose designed race cars like Formula 1-2-3-4, Formula Ford, F1600, F2000, etc, Indy Cars, IMSA Prototypes, Open Wheel Midgets & Sprint Cars. First, none of them have a body that originated as a production car. Second, they have no ride height rule, so they run almost on the ground & do not travel the suspension very far. Formula 1-2-3-4, Formula Ford, F1600, F2000, etc, Indy Cars, IMSA Prototypes are rear engine. The Open Wheel Midgets & Sprint Cars are front engine & run straight axles in front.

I have a lot of experience with these cars & their suspension & geometry needs are VERY different than full bodied track & road race cars with a significant ride height. All of them have around 60% rear weight bias. That changes the game completely. With these cars we're always hunting for more REAR grip, due to the around 60%+/- rear weight bias.

In all my full bodied track & road race cars experience ... Stock Cars, Road Race GT cars, TA/GT1, etc. ... with somewhere in the 50%-58% FRONT bias ... we know we can't go any faster through the corners than the front end has grip. So, what we need to do, compared to Formula 1-2-3-4, Formula Ford, F1600, F2000, etc, Indy Cars, IMSA Prototypes, Open Wheel Midgets & Sprint Cars, is very different.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Before we get started, let's get on the same page with terms & critical concepts.

Shorthand Acronyms

IFT = Inside Front Tire

IRT = Inside Rear Tire

OFT = Outside Front Tire

ORT = Outside Rear Tire

*Inside means the tire on the inside of the corner, regardless of corner direction.

Outside is the tire on the outside of the corner.

LF = Left Front

RF = Right Front

LR = Left Rear

RR = Right Rear

ARB = Anti-Roll Bar (Sway Bar)

FLLD = Front Lateral Load Distribution

RLLD = Rear Lateral Load Distribution

TRS = Total Roll Stiffness

LT = Load Transfer

RA = Roll Angle

RC = Roll Center

CG = Center of Gravity

CL = Centerline

FACL = Front Axle Centerline

RACL = Rear Axle Centerline

UCA = Upper Control Arm

LCA = Lower Control Arm

LBJ = Lower Ball Joint

UBJ = Upper Ball Joint

BJC = Ball Joint Center

IC = Instant Center is the pivot point of a suspension assembly or "Swing Arm"

CL-CL = Distance from centerline of one object to the centerline of the other

KPI = King Pin Inclination, an older term for the angle of the ball joints in relation to the spindle

SAI = Steering Angle Inclination, a modern term for the angle of the ball joints in relation to the spindle

TERMS:

Roll Centers = Cars have two Roll Centers ... one as part of the front suspension & one as part of the rear suspension, that act as pivot points. When the car experiences body roll during cornering ... everything above that pivot point rotates towards the outside of the corner ... and everything below the pivot point rotates the opposite direction, towards the inside of the corner.

Center of Gravity = Calculation of the car's mass to determine where the center is in all 3 planes. When a car is cornering ... the forces that act on the car to make it roll ... act upon the car's Center of Gravity (CG). With typical production cars & "most" race cars, the CG is above the Roll Center ... acting like a lever. The distance between the height of the CG & the height of each Roll Center is called the "Moment Arm." Think of it a lever. The farther apart the CG & Roll Center are ... the more leverage the CG has over the Roll Center to make the car roll.

Instant Center is the point where a real pivot point is, or two theoretical suspension lines come together, creating a pivot arc or swing arm.

Swing Arm is the length of the theoretical arc of a suspension assembly, created by the Instant Center.

Static Camber is the tire angle (as viewed from the front) as the car sits at ride height. Straight up, 90 degrees to the road would be zero Camber. Positive Camber would have the top of tire leaned outward, away from the car. Negative Camber would have the top of tire leaned inward, towards the center of the car.

Camber Gain specifically refers to increasing negative Camber (top of wheel & tire leaning inward, towards the center of the car) as the suspension compresses under braking & cornering.

Total Camber is the combination of Static Camber & Camber Gain ... under braking, in dive with no roll & no steering, as well as the Dynamic Camber with chassis roll & steering.

Dynamic Camber refers to actual angle of the wheel & tire (top relative to bottom) ... compared to the track surface ... whit the suspension in dive, with full chassis roll & a measure of steering. In others, dynamically in the corner entry. For our purposes, we are assuming the car is being driven hard, at its limits, so the suspension compression & chassis/body roll are at their maximum.

Static Caster is the spindle angle (viewed from the side with the wheel off). Straight up, 90 degrees to the road would be zero Caster. Positive Caster would have the top of spindle leaned back toward to cockpit. Negative Caster would have the top of spindle leaned forward towards the front bumper.

Caster Gain is when the Caster angle of the spindle increases (to the positive) as the suspension is compressed, by the upper ball joint migrating backwards and/or the lower ball joint migrating forward ... as the control arms pivot up. This happens when the upper and/or lower control arms are mounted to create Anti-dive. If there is no Anti-dive, there is no Caster Gain. If there is Pro-Dive, there is actually Caster loss.

Anti-Dive is the mechanical leverage to resist or slow compression of the front suspension (to a degree) under braking forces. Anti-dive can be achieved by mounting the upper control arms higher in the front & lower in the rear creating an angled travel. Anti-dive can also be achieved by mounting the lower control arms lower in the front & higher in the rear, creating an angled travel. If both upper & lower control arms were level & parallel, the car would have zero Anti-dive.

Pro-Dive is the opposite of Anti-dive. It is the mechanical leverage to assist or speed up compression of the front suspension (to a degree) under braking forces. Provide is achieved by mounting the upper control arms lower in the front & higher in the rear, creating the opposite angled travel as Anti-Dive. Pro-dive can also be achieved by mounting the lower control arms higher in the front & lower in the rear, creating the opposite angled travel as Anti-Dive.

Split is the measurement difference in two related items. We would say the panhard bar has a 1" split if one side was 10" & the other side 11". If we had 1° of Pro-Dive on one control arm & 2° of Anti-Dive on the other, we would call that a 3° split. If we have 8° of Caster on one side & 8.75° on the other, that is a .75° split.

Scrub Radius = A car's Scrub Radius is the distance from the steering axis line to tread centerline at ground level. It starts by drawing a line through our upper & lower ball joints, to the ground, that is our car's steering axis line. The dimension, at ground level, to the tire tread centerline, is the Scrub Radius. The tire's contact patch farthest from the steering axis loses grip earliest & most during steering. This reduces the tire's grip on tight corners. The largest the Scrub Radius, the more pronounced the loss of grip is on tight corners. Reducing the Scrub Radius during design increases front tire grip on tight corners.

Baseline Target is the package of information about the car, like ride height, dive travel, Roll Angle, CG height, weight, weight bias, tires & wheel specifications, track width, engine power level, estimated downforce, estimated max corner g-force, etc. We call it "Baseline" ... because it's where we're starting at & "Target" because these key points are the targets we're aiming to achieve. We need to work this package of information prior to chassis & suspension design, or we have no target.

Total Roll Stiffness (aka TRS) is the mathematical calculation of the "roll resistance" built into the car with springs, Sway Bars, Track Width & Roll Centers. Stiffer springs, bigger Sway Bars, higher Roll Centers & wider Track Widths make this number go UP & the Roll Angle of the car to be less. "Total Roll Stiffness" is expressed in foot-pounds per degree of Roll Angle ... and it does guide us on how much the car will roll.

Front Lateral Load Distribution & Rear Lateral Load Distribution (aka FLLD & RLLD):

FLLD/RLLD are stated in percentages, not pounds. The two always add up to 100% as they are comparing front to rear roll resistance split. Knowing the percentages alone, will not provide clarity as to how much the car will roll ... just how the front & rear roll in comparison to each other. If the FLLD % is higher than the RLLD % ... that means the front suspension has a higher resistance to roll than the rear suspension ... and therefore the front of the car runs flatter than the rear of the suspension ... which is the goal.

Roll is the car chassis and body "rolling" on its Roll Axis (side-to-side) in cornering.

Roll Angle is the amount the car "rolls" on its Roll Axis (side-to-side) in cornering, usually expressed in degrees.

Dive is the front suspension compressing under braking forces.

Full Dive is the front suspension compressing to a preset travel target, typically under threshold braking. It is NOT how far it can compress.

Rise = Can refer to either end of the car rising up.

Squat = Refers to the car planting the rear end on launch or under acceleration.

Pitch = Fore & aft body rotation. As when the front end dives & back end rises under braking or when the front end rises & the back end squats under acceleration.

Pitch Angle is the amount the car "rotates" fore & aft under braking or acceleration, usually expressed by engineers in degrees & in inches of rise or dive by Racers.

Diagonal Roll is the combination of pitch & roll. It is a dynamic condition. On corner entry, when the Driver is both braking & turning, front is in dive, the rear may, or may not, have rise & the body/chassis are rolled to the outside of the corner. In this dynamic state the outside front of the car is lowest point & the inside rear of the car is the highest point.

Track Width is the measurement center to center of the tires' tread, measuring both front or rear tires.

Tread Width is the measurement outside to outside of the tires' tread. (Not sidewall to sidewall)

Tire Width is the measurement outside to outside of the sidewalls. A lot of people get these confused & our conversations get sidelined.

Floating typically means one component is re-engineered into two components that connect, but mount separate. In rear ends, a "Floater" has hubs that mount & ride on the axle tube ends, but is separate from the axle itself. They connect via couplers. In brakes, a floating caliper or rotor means it is attached in a way it can still move to some degree.

Decoupled typically means one component is re-engineered into two components that connect, but ACT separately. In suspensions, it typically means one of the two new components perform one function, while the second component performs a different function.

Spring Rate = Pounds of linear force to compress the spring 1". If a spring is rated at 500# ... it takes 500# to compress it 1"

Spring Force = Total amount of force (weight and/or load transfer) on the spring. If that same 500# spring was compressed 1.5" it would have 750# of force on it.

Sway Bar, Anti-Sway Bar, Anti Roll Bar = All mean the same thing. Kind of like "slim chance" & "fat chance."

Sway Bar Rate = Pounds of torsional force to twist the Sway Bar 1 inch at the link mount on the control arm.

Rate = The rating of a device often expressed in pounds vs distance. A 450# spring takes 900# to compress 2".

Rate = The speed at which something happens, often expressed in time vs distance. 3" per second. 85 mph. * Yup, dual meanings.

Corner Weight = What each, or a particular, corner of the race car weighs when we scale the car with 4 scales. One under each tire.

Weight Bias = Typically compares the front & rear weight bias of the race car on scales. If the front of the car weighs 1650# & the rear weighs 1350# (3000# total) we would say the car has a 55%/45% front bias. Bias can also apply to side to side weights, but not cross weight. If the left side of the car weighs 1560# & the right 1440#, we would say the car has a 52/42 left side bias.

Cross Weight = Sometimes called "cross" for short or wedge in oval track racing. This refers to the comparison of the RF & LR corner weights to the LF & RR corner weights. If the RF & LR corner scale numbers add up to the same as the LF & RR corners, we would say the car has a 50/50 cross weight. In oval track circles, they may say we have zero wedge in the car. If the RF & LR corner scale numbers add up to 1650# & the LF & RR corners add up to 1350#, we would say the car has a 55/45 cross weight. In oval track circles, they may say we have 5% wedge in the car, or refer to the total & say we have 55% wedge in the car.

Grip & Bite = Are my slang terms for tire traction.

Push = Oval track slang for understeer, meaning the front tires have lost grip and the car is going towards the outside of the corner nose first.

Loose = Oval track slang for oversteer meaning the rear tires have lost grip and the car is going towards the outside of the corner tail first.

Tight is the condition before push, when the steering wheel feels "heavy" ... is harder to turn ... but the front tires have not lost grip yet.

Free is the condition before loose, when the steering in the corner is easier because the car has "help" turning with the rear tires in a slight "glide" condition.

Good Grip is another term for "balanced" or "neutral" handling condition ... meaning both the front & rear tires have good traction, neither end is over powering the other & the car is turning well.

Mean = My slang term for a car that is bad fast, suspension is on kill, handling & grip turned up to 11, etc., etc.

Greedy is when we get too mean with something on the car, too aggressive in our setup & it causes problems.

Steering Turn-In is when the Driver initiates steering input turning into the corner.

Steering Unwind is when the Driver initiates steering input out of the corner.

Steering Set is when the Driver holds the steering steady during cornering. This is in between Steering Turn-In & Steering Unwind.

Roll Thru Zone = The section of a corner, typically prior to apex, where the Driver is off the brakes & throttle. The car is just rolling. The start of the Roll Thru Zone is when the Driver releases the brakes 100%. The end of the Roll Thru Zone is when the Driver starts throttle roll on.

TRO/Throttle Roll On is the process of the Driver rolling the throttle open at a controlled rate.

Trail Braking is the process of the Driver braking while turning into the corner. Typically, at the weight & size of the cars we're discussing here ... the Driver starts braking before Steering Turn-In ... and the braking after that is considered Trail Braking. This is the only fast strategy. Driver's that can't or won't trail brake are back markers.

Threshold Braking = The Driver braking as hard as possible without locking any tires, to slow the car as quickly as possible to the target speed for the Roll Thru Zone. Typically done with very late, deep braking to produce the quickest lap times.

#16

New Products & Product Spotlight / Product Spotlight - January 20...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 22, 2026, 01:52 PMProduct Spotlight - January 2026

Our complete Sway Bar kits have always been popular with DIY Car Guys, Racers & Fab Shops. When Speedway Engineering closed without notice, I scrambled & researched until I found the best replacement companies & products. Now, Speedway Engineering is back with new owners. they look to be doing good work & are catching up on backlogs of products.

I had utilized Speedway Engineering, with Kenny Sapper running it, for over 25 years. Never thought of shopping around. What I learned when I needed to replace them, was there are, in a few cases, better options. Only a few. But those options are good to add to our sway bar kit lineup.

The biggest things we changed or added are:

* 1.50" Step-Up Sway Bars over 1.75". They're lighter & achieve the same rates we need.

* Delrin Bushings instead of Nylon Bushings - Better Lubrication & Life

* 2.00" Tubular Race-Warrior Sway Bars made with 300M - Super Light & Quick Responding

* Monoball Bearing bushing for our 2.00" Race-Warrior Sway Bars

* Offset Sway Bar Arms, Made to Our Specifications - All Sizes

* Lightweight, Hollow, Chromoly, TIG welded, Race-Warrior Sway Bar Arms

So today, we utilize Speedway Engineering AND the new companies I found to work with. Adding an even more robust line of Sway Bar Kits front & rear.

You can see these in every "Race Car in a Box" package, as well as individually in the Component Kits & Technical Services catalog HERE. See pages 96-131.

#17

Company Updates & Notices / January 2026 - Updates

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 22, 2026, 01:36 PMWhat's New for January 2026

Some of you don't know, but I went through some health problems, 3 surgeries & cancer treatment. My wife retired & we moved to Florida just before that mess. Now I'm back. I'm only 62 & expect to do this for the next 20 years. I'm not messing around either. I have a new website home page, 7 new catalogs & a robust technical forum here at BrakeTurnGo.com.

I look forward to interacting with you on here, as well as assisting a number of you with your builds. I love seeing new race cars come together & then kick ass on track.

7 New Catalogs:

Tube Chassis

Race-Warriors

Vintage-Warriors

Track-Warriors

Muscle Car

Autocross

AutoX + Track

Track + Race

Individual Items & Services

Component Kits & Technical Services

My new "Race Car in a Box" packages in all the Catalogs but the last, are meant to help you get everything you need to build a rolling chassis. Either all at once, or front, rear, brakes & cage a piece at a time. These are truly designed for the DIY Racer, Car Guy or Fab Shop. They come with a complete suspension setup, optimized geometry & full alignment specs. Build it. Track It. Race it. Win.

Race-Warriors are for Pro Level racing in SCCA GT classes, Trans Am classes & specific classes in Australia, New Zealand & the United Kingdom. These are full on race cars with no corners cut. They will be competitive the moment they are built. Pick a class of racing where tube chassis race cars fit, and we probably have a "Race Car in Box" Race-Warrior package to build your winning race car. A lot of modern (and Vintage) bodies are available.

Vintage-Warriors are for Vintage racing fun. They fit in SVRA & HSR classes for vintage IMSA & Trans Am race cars. They have the period correct look, but modern geometry & track performance. If you can't find that Fill In the Blank Here road race car you loved back in the day ... just build your own. Maybe you did find the u] Fill In the Blank Here [/u] road race car you loved back in the day ... but they wanted a kidney & a lung for it ... just build your own. We know where most of the Vintage Trans Am & IMSA body molds are. With one of our "Race Car in a Box" Vintage-Warrior packages & your favorite Trans Am or IMSA body, you can build your dream car. Then race it with other Vintage gentlemen racers.

Track-Warriors are for Track day fun. They can be raced. We consider them more practical & budget friendly than Race-Warriors. But the number one goal is for you to build your own track car in your garage or shop. Knowing it will perform as soon as it's built. You can build yours with any car body you want. Maybe it's unique car you loved years ago, a muscle car you already have or a brand new composite body you like. With one of our "Race Car in a Box" Track-Warrior packages, you can build your dream car. Then track it for fun, or race it in the open classes with NASA, SCCA, NE GT, EMRA, WRL & others. Also great to build tube chassis Time Attack cars. Any body you want.

A Note on Composite Bodies: We post them in the catalog just as a resource for racers building a new Track, Vintage or Modern Race Car. We do NOT sell bodies or body components. We are in the Build Your Own chassis business. We offer the "race Car in a Box" packages ALONG WITH everythinbg else you need to build your car ... with two exceptions ... powertrain & body.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Autocross Catalog is for 60's to 90's Muscle Cars. If you want to build your Muscle Car into the best performing autocross competitor, this is for you. These "Race Car in a Box" packages are specifically optimized for Autocross & nothing else. You can be assured of having a competitive autocrosser the moment it is built.

AutoX + Track Catalog is for 60's to 90's Muscle Cars. If you want to build your Muscle Car into a dual purpose, autocross competitor & track car, this is for you. These "Race Car in a Box" packages are specifically designed & optimized to switch from Autocross to Track with quick, easy changes. These packages that allow you to build you own dual purpose, kick ass performing muscle car, are perfect for competitions like the GTV class of the Optima Ultimate Street Car Challenge. You can be assured of having a competitive car the moment it is built.

Track + Race Catalog is for 60's to 90's Muscle Cars. If you want to build your Muscle Car into a track car or road race muscle car, this is for you. This catalog is broken into two sections ... Track & Race. In the Race Section, I offer packages for Fords & GM Muscle Cars to race in NASA American Iron or American Iron Extreme. Those classes require you run the OEM Factory clip, but allow modifications. I designed the new "Star System" control arm & shocks mounts, as well as the AXT-Star steering system, specifically to race & win in these classes,

The Track "Race Car in a Box" packages are specifically designed & optimized to build your muscle car into a great Track Car. These packages that allow you to build you own kick ass performing track car in your garage or shop. Knowing it will handle well & perform great as soon as it's built. The Track-Star is the King of Hill in this section. They utilize the same suspension & steering systems I put in the American Iron & Extreme race cars. Giddy up!

Lastly, the catalog for Component Kits & Technical Services, are for DIY car guys & racers wanting to build their own bad ass race car, without one of my race car in a box packages. You can purchase my Tech Services there to ensure you have optimum suspension setup, geometry & full alignment specs. Then you can pick & choose which RSRT component kits you need, one at a time.

#18

Rules of the Road for This Forum Website / Re: Rules of BrakeTurnGo.com F...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 22, 2026, 12:43 PMI have listed 12 topic categories on the main page.

The first 5 are complete with content. They are the most important, in my opinion. All members can post replies to ask questions or make statements. Gold members you can start new topic threads whenever you want.

The next two topic categories I'm adding content threads for, in January, are:

*In Shop - Race Car Setup, Scaling & Alignment

*Track Tuning Techniques for Overall Handling Balance

After that, in February, I'll add content threads in:

*Designing in Safety for Track & Racing

*Designing & Tuning Aerodynamics for Track & Racing

*Driving Tips & Techniques for Track & Racing

I'll probably get to the last one in March:

*KERB & CEPS Strategies for Racing Improvement

You currently can not post in topics with an *. You will be able to once I post my content.

The first 5 are complete with content. They are the most important, in my opinion. All members can post replies to ask questions or make statements. Gold members you can start new topic threads whenever you want.

The next two topic categories I'm adding content threads for, in January, are:

*In Shop - Race Car Setup, Scaling & Alignment

*Track Tuning Techniques for Overall Handling Balance

After that, in February, I'll add content threads in:

*Designing in Safety for Track & Racing

*Designing & Tuning Aerodynamics for Track & Racing

*Driving Tips & Techniques for Track & Racing

I'll probably get to the last one in March:

*KERB & CEPS Strategies for Racing Improvement

You currently can not post in topics with an *. You will be able to once I post my content.

#19

Methods & Strategies to Increase Overall Grip for Track & Racing / Re: Methods & Strategies to In...

Last post by Ron Sutton - Jan 21, 2026, 06:44 PMBonus Tip #1: Not Grip Related > But Increasing Rolling Speed

I'm a fan of bearing spacers & run them often in race car applications. These are adjustable for width & go in between two tapered roller bearings. They allow you to set the preload on the bearings without over torquing them. Frankly, the thrust load is already distributed to both bearings, regardless of running a bearing spacer. A spacer does not increase the thrust load capability of either bearing, so the small, weak outer bearing is still the weak link.

Bearing spacers allow the bearings to be fully tightened and yet have minimal preload & drag. So, they make the rolling friction less. Moreso on straights, because in corners, the bearings are still side loaded. Even with that side load, THE RACE CAR SLOWS DOWN LESS in the roll through zone with bearing spacers. Simply put, they "free up horsepower" by requiring less power to accelerate & achieve speed. We run them in between the rear floater hub bearings too.

This does reduce bearing temperature, which is a cause of a bearing failure. So, they also increase bearing life. it doesn't change the thrust load capacity of the hub bearings, so you still need to get the best ones that your budget allows. Would I suggest you run bearing spacers? Absolutely. They will "help" your bearing, by reducing the heat ... and they help your car by reducing rolling friction.

Bonus Tip #2: Not Grip Related > But Increasing Rolling Speed

I'm a fan of micro polishing gears & bearings. Why? So many key reasons:

1. They reduce the rolling friction

2. Therefore, they increase total speed possible

3. The race car slows down less in the roll through zone

4. Polished gears & bearings generate less heat & last longer

5. Polished gears are quieter

6. Polished gears do not require any "break-in" time or procedure

Bonus Tip #3: Not Grip Related > But Increasing Rolling Speed

I'm a fan of friction reducing coatings. Why? Lot of reasons:

1. They reduce the rolling friction, similar to bearing spacers & polished gears

2. Therefore, they increase total speed possible

3. The race car slows down less in the roll through zone

4. Friction Coated gears generate less heat & last longer

*The gears below are Moly Koted

Bonus Tip #4: Not Grip Related > But Increasing Rolling Speed

I'm a fan of ProBlend metal treatment. Why? A couple of reasons. If ... if ... if you don't spend the time & money to micro polish gears or have them coated for friction reduction, ProBlend metal treatment is the next best thing. ProBlend is an oil additive, but doesn't treat the oil. The oil is just the carrier of ProBlend to the metals. Once there, ProBlend treats the metal to have lower friction.

1. ProBlend additives reduce the rolling friction, similar to coatings & polished gears

2. ProBlend additives increase total speed possible

3. The race car slows down less in the roll through zone

4. Gears generate less heat & last longer with ProBlend additives

26. Suspension Bind

The most common mistake Racers make is not checking for suspension bind. Then the car handles bad at the track, usually in ways that don't make sense initially.

An autocross client had a professional shop install his new Speedtech front clip, front & rear suspension. It would drive "OK" at lower speeds, but when driven fast, all four tires would break away & drift. When he explained this, Ron told him the suspension is bound up. "No way. They were a Professional Shop" and other reasons were suggested. When he inspected it himself, all the suspension was bolted (impacted) into WAY too tight & bound up.

When he removed the coil-overs, the front control arm assemblies and the rear suspension would not move freely. This KILLS grip. Before your car leaves the shop, remove the wheels, coil-overs & one link on each sway bar. Each control arm assembly needs to freely move up & down throughout the useful travel range. The rear axle needs to go up & down, plus articulate freely. Then, with a helper, check it all with the sway bars attached.

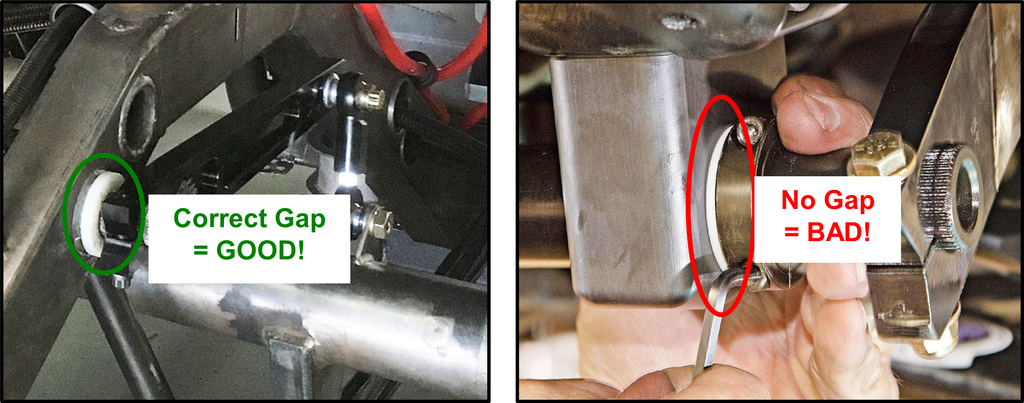

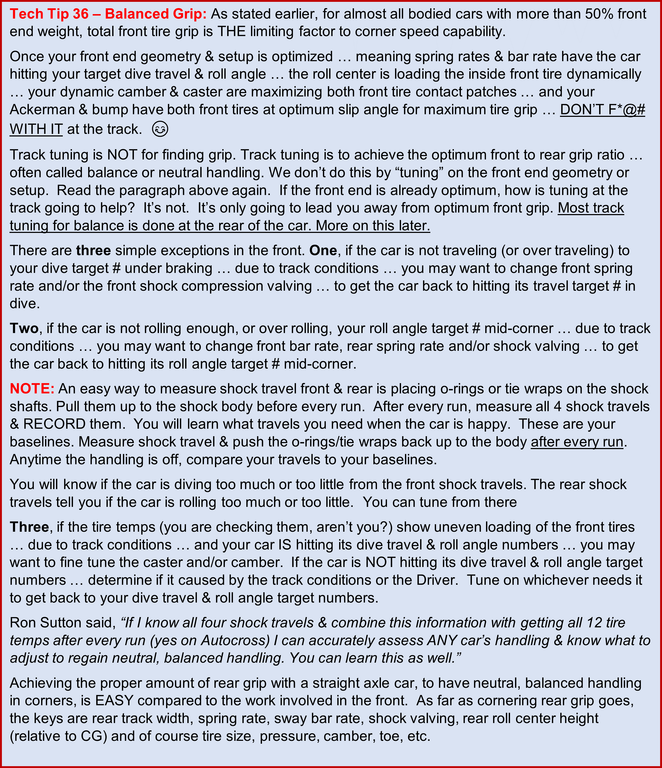

Sway bars binding up is super common. We had a Racer run zero gap on each side of his splined sway bars front & rear. The car handled OK at lower speeds. But, at higher speeds & roll angle, the car lost total grip. News Flash: Sway bars (and torsion bars) get shorter as they twist. His sway bars were binding & shooting the rates to infinity. He added gap on each side & the car handled great.

Another client built his tube chassis car from scratch, but didn't check for suspension bind. He had sway bar linkage binding against the lower control arms. With a Monster 1-3/4" GT/NASCAR sway bar ... it literally broke the lower control arms ... under hard braking. Another sway bar bind situation I ran into was the racer was using typical bronze lined pillowblock bushings.

As you can see from the photo above, the bronze bushings are made for rotation of the sway bar, but side-to-side articulation. These work "OK" if you have zero flex in the chassis. But if the chassis flexes, they will bind up. That is eaxactly what this racer did. The solution is to pillow block bushings with a monoball in it to rotate any direction. See our Delrin monoball bushings below. They will allow the sway bar to operate bind free, regardless of any frame flex.

27. Chassis Flex

When you think about it, all chassis are rigid or flexible to some degree. No chassis is 100% rigid with zero flex, and if it is, you built it waaaaaaay too heavy. Rigidity in a chassis makes the car more responsive to driver input & tuning changes & creates more grip. Flexibility in a chassis makes the car less responsive to driver input & tuning changes ... and has less grip.

The lower grip is due to energy loss from the chassis flexing too much. I use an electrical analogy. Think about if we plug in a super heavy gage wire extension cord, going only 10'. It will not see very much amperage loss, if any. Now make that extension cord 100' & the amperage loss is measurable. Now replace that extension cord with a very small gage wire. The amperage loss will be huge. This is energy loss due to an inferior structure.

Race cars are the same. Most production cars are limp noodles & flex way too much. Some race cars are over designed & too rigid for their application. I've had cars that were too flexible. It was hard to make them fast due to their lack of grip. The flexy chassis just gave up too much grip to be fast. I've had race cars that were too rigid.

When I got into USAC Midget racing, I bought a used race car. I could see it was a more rigid design than others. Man, that thing was fast! For 10 laps. It was TOO SENSITIVE. As the track would rubber up on a 30-50 lap race, this car's handling would change significantly. We had to decide which 10 laps we wanted that car fastest. LOL

Our biggest competitor in the USAC Midget chassis business had a little trick up his sleeve. I could see the difference between his "House Car" & his customer cars. His cars had additional bracing to be more rigid. When I asked him about it, he grinned & said, "My customers are not constant tuners like you & I are. By making my customer cars softer, the car is less sensitive. It works OK at most tracks & track changes don't affect it as much. I make mine stiffer, which requires being more spot on the setup, but our car is faster."

Our 23 AutoX & Track-Warrior chassis vary in rigidity, depending upon how much power, tire, weight & g-force loads they're designed for ... and what is the priority ... a wide tuning widow -OR- every bit of lap time possible. It's not a one-size fits all. The same can be said for our 8 Race-Warrior chassis. They vary from each other based on power, tire, weight & g-force loads. All 4 of these chassis are designed for 700HP, but very different applications, different g-loads & different goals.

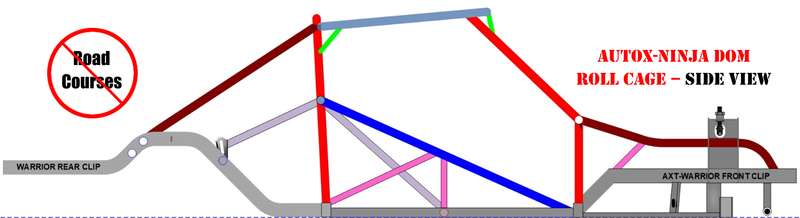

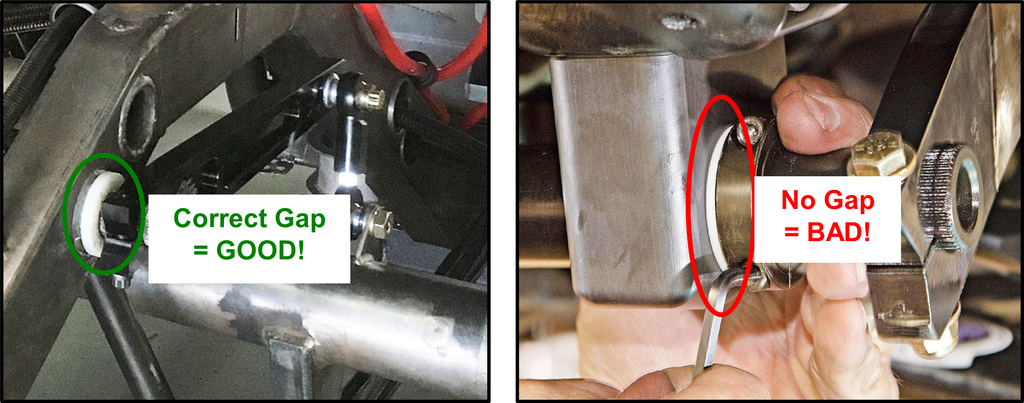

See the 4 chassis images below. The first one is called our AutoX-Ninja. Ninja because it's light & quick. It provides just enough rigidity for a 2600-2800# featherweight autocross car with 700HP. It has no place on a road course. It does NOT provide enough safety in my race car designer opinion. Nor does it have enough rigidity to handle road course g-forces.

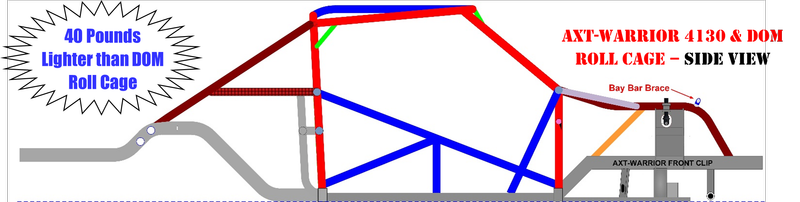

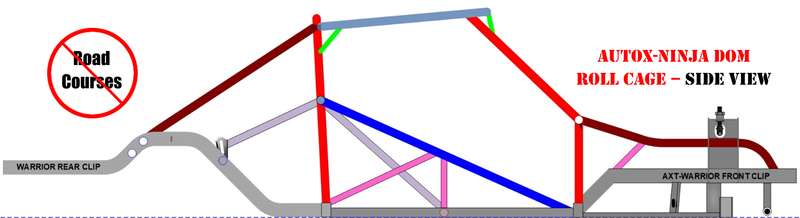

The second image, right below here, is our AXT-Warrior, designed for double duty track days & autocross. Same frame. Much safer roll cage design for the higher speeds seen on road courses. This chassis is also designed for 700HP, but more rigid to handle road course level g-forces in the 1.7 range. Compare details.

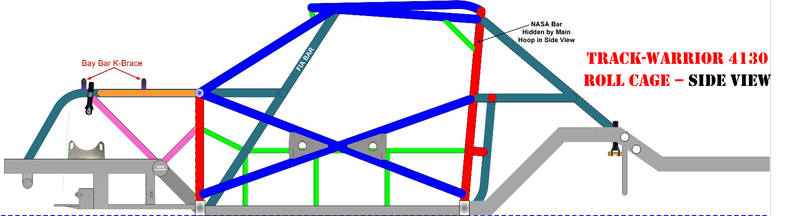

Compare the AXT-Warrior above to a Track-Warrior chassis below, designed to a full time track car or budget road race car with up to 700HP. The additions in structure are to make the Track-Warrior both faster & safer at g-loads near 2.0g. If all things were equal, weight, aero, power, etc. ... the Track-Warrior chassis will run faster lap times, but have a narrower tuning range than the AXT-Warrior.

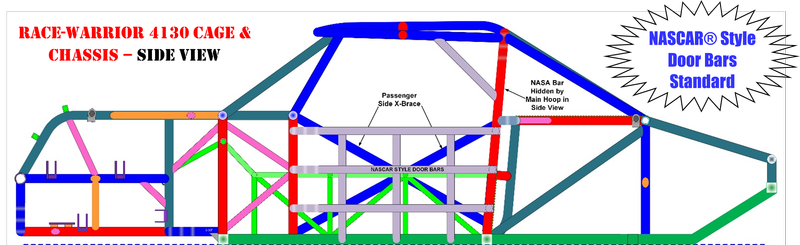

Now, below is a full blown Race-Warrior chassis, also meant for 700HP in top level road racing. Very different level of rigidity designed in. It is extremely stiff. Designed for loads well over 2g. This is meant for pro level road racing where every tenth of a second is precious. If all things were equal, weight, aero, power, etc. ... the Race-Warrior chassis will run faster lap times, but have a narrower tuning range than the Track-Warrior.

Summary: There is more detail & information on this area in the forum thread "suspension Strategies for Track & Racing." The key thing to know is if the chassis is too soft, too flexible, you will be giving up some grip. Conversely, if the chassis is too stiff, too rigid, it will have high grip, but in a narrow tuning range. Your goal is to have a race car chassis rigid enough to be fast & flexible enough to have a managable tuning sweet spot.

28. Aero Downforce

It feels kind of silly needing to talk about achieving grip with downforce in this section. So I'll keep it simple here & you can read in more depth & detail on how to do this in the "Designing & Tuning Aerodynamics" forum thread on this website.

Remember increasing front grip from aero downforce is just as important, if not more important, than the increasing rear grip with aero downforce. It's easier to get high amounts of additional grip on the rear tires by simply buying & installing a big ol wang or big spoiler. Easy peasy.

If you're not 100% clear on how spoilers work to create downforce, here it is. The spoiler itself is not where the downforce is. The spoiler just slows the airflow over the back of the race car to create a high pressure area in front of the spoiler. The trunk or decklid, as most call it. The flat area is where the downforce is created. The taller the spoiler and/or the steeper the angle of the spoiler defines how high the pressure area is.

The size of the usuable flat surface area plays a role in the rear downforce. The degree of high pressure & the amount of square inches of usuable surface area together define the actual rear downforce. So, a larger and/or flatter trunk or deck lid can create more downforce, if the high pressure created is the same.

The trunk/decklid needs to be strong enough to not flex away the downforce. Just like energy loss in chassis, springs & other areas, if the body panel the airflow is pushing on FLEXES, it is not going to be 100% efficient or effective. I've seen body panels flex up to 75 pounds before the chassis moved one iota. Nothing. That 75# of flex is 75# of downforce lost. So we need rigidity in the body panels we're creating downforce on.

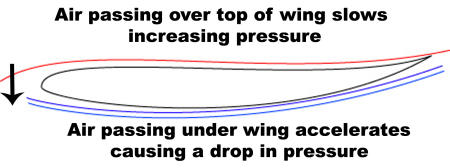

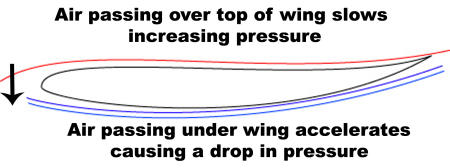

Wings are different animals. The downforce is created on the top of the wing surface. So more surface area (of the same wing shape) creates more downforce. The shape of the wing itself plays a big role in both downforce & drag. The closer to flat the top of the wing is, the less downforce & less drag. The more the middle of the wing cord dips down, assuming the design is good, the more downforce & drag created.

AoA, Angle of Attack plays a a key part in how much downforce a wing can make. Basically, for most wings, if the top of the wing cord is level, that will be the lowest downforce & drag position. As you increase the angle of the wing (AoA) the downforce & drag will increase ... up to a point. Every wing shape has a specific stall angle. With each wing shape, there is an AoA in which the downforce stops increasing, but the drag increases continue.

The front is harder. Increasing front grip from aero downforce is a lot more work. Well, getting some downforce in the front is easy. Getting enough front downforce can be challenging. The easy part in the front is building an airdam, then adding a splitter. The height of the airdam/splitter combination needs to work with your suspension travel strategy. The longer the splitter is, going out & forward, the more surface area it has for high pressure to push down on it. You'll notice strut braces on splitters in the photo. Anytime the splitter is more than a couple inches, the downforce will bend them down, losing some of your downforce to energy loss & probably losing a splitter to the track.

Of course we have to create this high pressure zone. The best is an air dam that is either straight up or angled inward to "catch" the air flow in the front. We literally want to stall the airflow here to create a high pressure zone, to push down on the splitter. (See yellow car below) This is not the place to pull engine or brake cooling from, if you want maximum front downforce. (See white car below)

The harder part, but very important is creating downforce over the hood of the car. How well the airflow in the front area of the car flows over the hood is dependant on a few things. First is the smooth roundness of the top of the nose, where it meets the hood. If the top of the nose is not smooth & round, we will see less airflow at the front of the hood. This means we're only utilizing the rear portion of the hood, as airflow gets on it.

The hood surface area has similar needs to the deck lid in the rear. The flat area is where the downforce is created. What's different is the windsheild is our spoiler. The windsheild is what slows the airflow to create a high pressure zone on the hood of our race car. The taller the windshieild and/or the steeper the angle of the windsheild defines how high the pressure area is.

The size of the usuable flat or concave hood surface area plays a role in the front downforce. The degree of high pressure & the amount of square inches of usuable surface area together define the actual front downforce at the hood. So, a larger, flatter & cleaner hood can create more downforce, if the high pressure created is the same. Look at the shear size & surface area of the hood on the yellow Mustang above.

The hood needs to be supported enough to not flex away the downforce. Just like energy loss in chassis, springs & other areas, if the hood the airflow is pushing on FLEXES, it is not going to be 100% efficient or effective. I've seen hoods flex up to 120 pounds before the chassis moved one iota. Nothing. That 120# of flex is 120# of downforce lost. So we need rigidity in the body panels we're creating downforce on.

What hurts smooth airflow over the hood, & takes away downforce, are obstacles to airflow on the hood. Funky shaped hood scoops, Injectors or air filters & other odd obstructions all create trubulence & reduce downforce on the hood. Vents typically (not always) reduce downforce, but are sometimes necessary regardless. I am a fan of well designed vents over the tops of the front tires, if the car has a smooth belly pan. This helps get some of that turbulent air out of the wheelwell. If the car doesn't have a full belly pan, I haven't seen much gain form vents. Mainly downforce loss.

Radiator ducting through the hood may, or may not, reduce downforce. It is a gain/loss situation, where we're hoping to gain more than we lose. I see a lot of homemade radiator ducting coming out of hoods. I realize some do it for cool factor. Some do it better cool the engine. Some do it thinking they're increasing downforce, but most fail at this.

Yes, creating a clean pathway for the airflow to go through the radiator, up & out the hood DOES provide some downforce. The question of loss we have is how much of the downforce the hood makes, was lost from this disruption in the hood's airflow surface. IF, the airflow coming up & out of the hood ducts crashes into the over hood airflow, frankly we'll create more trubulence & a higher downforce loss than we gained from the radiator hood ducting.

My friend Joey Hand raced for BMW for awhile before going to Ford & winning the 24 Hours of Daytona, 12 Hours of Sebring, 24 Hours of Lemans & much, much more in Grand Am & IMSA. So I follow his racing somewhat. The BMW's he raced utlized radiator ducting through the hood. I was told the aero engineers spent days with several hood & duct models in the wind tunnel working it out. What they landed on blended the radiator ducted airflow onto the hood & windsheild very smoothly. It is my opinion, to do this well, and expect to see a downforce increase, requires some pretty smart people & a wind tunnel. Otherwise you just guessing.

Having said that, I prefer to incorporate well designed side vents into the front fenders to evacuate hot air out of the radiator, engine compartment & tire wheelwell. It requires a radical fender rework to achieve this (see Callaway C7 be3low) but it leaves the full hood open as a downforce platform.

Canards on the leading edge of the front fenders are a nice addition to add some downforce. Most are small & offer small gains, but it still a measurable gain for the front. They help create some front downforce, & if effective, get the airflow out & away from the tires. (See red car below) There is a LOT more to learn in the Designing & Tuning Aerodynamics forum thread.

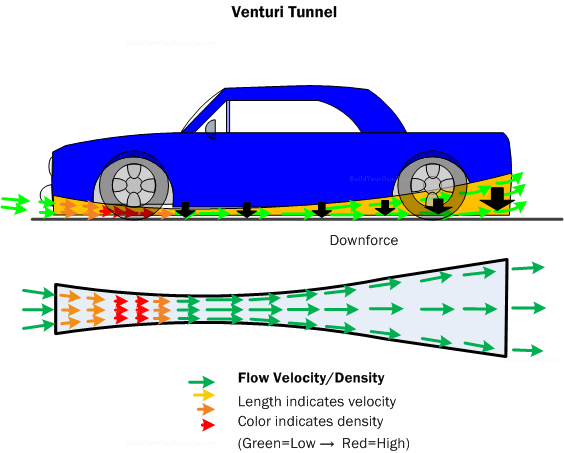

29. Aero Lift

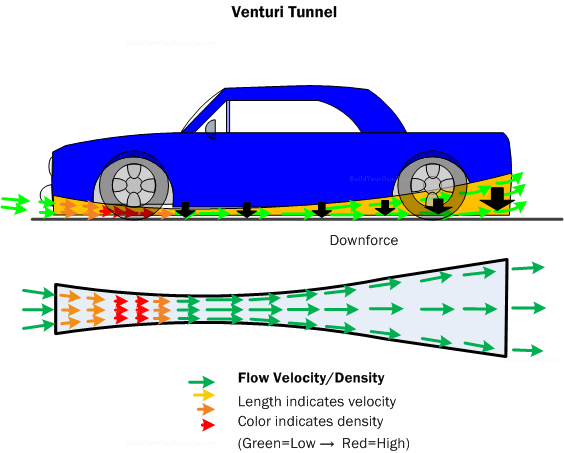

Reducing lift under the bottom of the race car is just as effective as increasing downforce over the top. In most cases with full bodied race cars, there is NOT as much downforce to be found under the car, as over. But it all adds up.

First, and most important is a full belly pan under the car. Without it, you have a mess under there. Visualize this. In your mind, flip the non belly pan race car over and ask yourself how smooth the airflow will be over that mess? Hell there are crossmembers running perpendicular to the race car centeline. Ok, flip the car rightside up.

All of the obstacles under your race car are slowing down airflow, creating a high pressure zone. This high pressure is pushing UP on the , hood, floorboard & truck area of your race car, creating lift. Obviously, lift is the opposite of downforce. Not good. If you can, if your rules allow, you will see a nice lift reduction, or downforce increase, based on your point of view, from running a full, smooth belly pan.

Next would be building & running an effective rear diffuser. The diffuser's role is to speed up the airflow as it exits the back of the car AND to help this airflow BLEND into the airflow over the race car. In my experience there will be turbulence & drag were the airflow under the car meets the airflow over the car. We're not going to eliminate it. But we can reduce it.

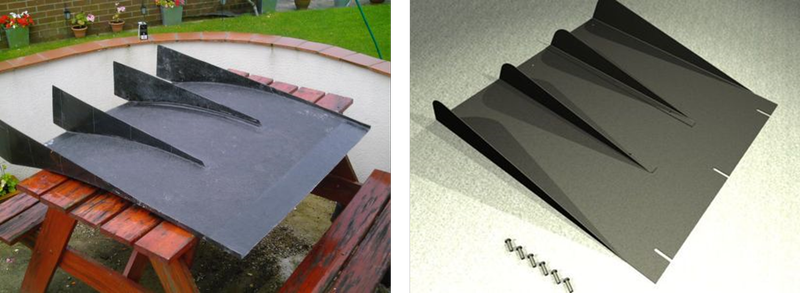

Most diffusers ... I said most, LOL ... on OEM cars are for looks. They don't work for shit. The most effective diffusers are long, wide & arch up in a GENTLE curve like the image below on the left. The one on the right with a flat surface you angle up will be effective. Just not as much as the gentle curved unit. But I'd much rather have a long, straight diffuser than a short one with an aggressive curve. The airflow won't follow an aggressive curve, so that type of diffuser is barely effective if at all.

A smooth belly pan, leading into a well designed rear diffuser will reduce the turbulence at the back of the car. This reduction in turbulence is also a reduction in aero drag. So the race car also picks up straight away speed. Bonus.

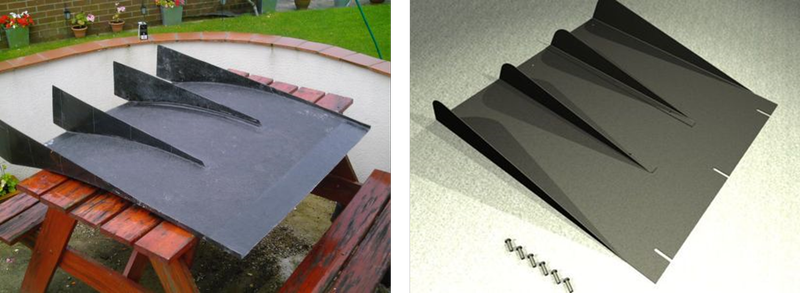

If you are going to do the full Monty with a full, smooth belly pan & well designed rear diffuser, you should modify your front splitter design. It needs to step up in the middle. (See image below) It needs to have a short, but wide, opening right in the middle, to force a small amount of ariflow through it, to the belly pan. This creates a venturi tunnel of sorts, and will make the belly pan & diffuser MORE EFFECTIVE, than simply running a regular splitter that blocks off air.

On the other hand, if you're NOT running a diffuser, even with a belly pan, a straight splitter that blocks off the airflow works better. You may like the look of the newer "Stepped" splitter. But it only adds downforce when paired with a full belly pan & diffuser.

A key area to reduce lift was mentioned above in the Aero Downforce section. That is venting out the hot, high airflow coming into the engine compartment & through the radiator. If not vented, this will literally create a high pressure are pushing up on the hood, taking away front downforce. Not good. Radiator extractors ducting through the hood can be challenging to get aero effective. I am more a fan of side airflow extractors, that blend into the side airflow, which we're not using much, if at all.

Another great tool to reduce lift are "Ground Effects" we started seeing in the 1980's or side splitters, we often see on modern sports cars like Corvettes. Both have the same goal, to solve a problem. The problem is the curved body panels on the sides of production cars. This is really prominent in cars from the 60's to the 90's, where you see the beltline of the car is the widest point.

Look at your door. If you look down the side of the car, it's clear the body curves under, at the beltline. What this means to us is the airflow going down both sides of the car is ROLLING UNDER the car, from the beltline down. Ground effects we're designed to attach to the rolled under doors & fenders to stop this. Most, if well designed, actually rolled out at the bottom edge. This was to give the airflow a "lane" to flow down the side of the car & not under.

More modern cars are built with much less rolled doors & fenders. Many incorporate what would be considered smaller ground effects. They are basically a lip to prevent the side airflow from rolling under. C5 through C7 Corvettes have a small roll under area. But many of the performance packges include side skirts. They basically a short panel that stick out a bit, stopping that airflow rolling under. All to stop lift. Aftermarket "side skirt" kits exist for many newer cars. But if you're building a track or race car, you can make this. Wider is better.

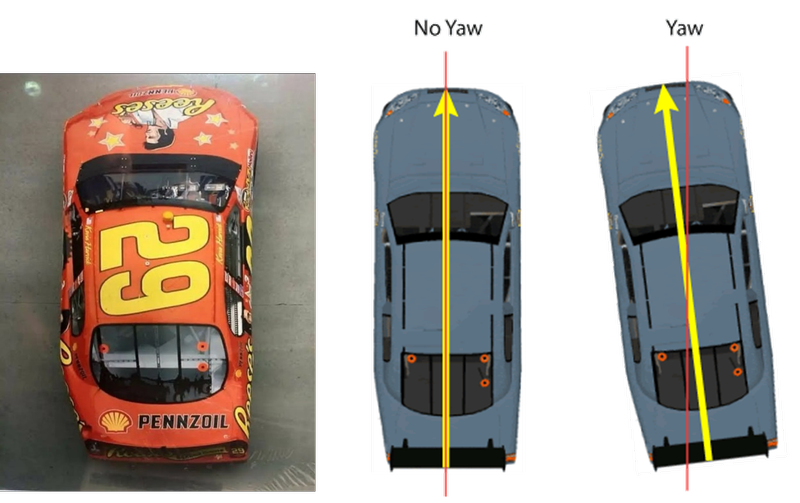

30. Aero Sideforce

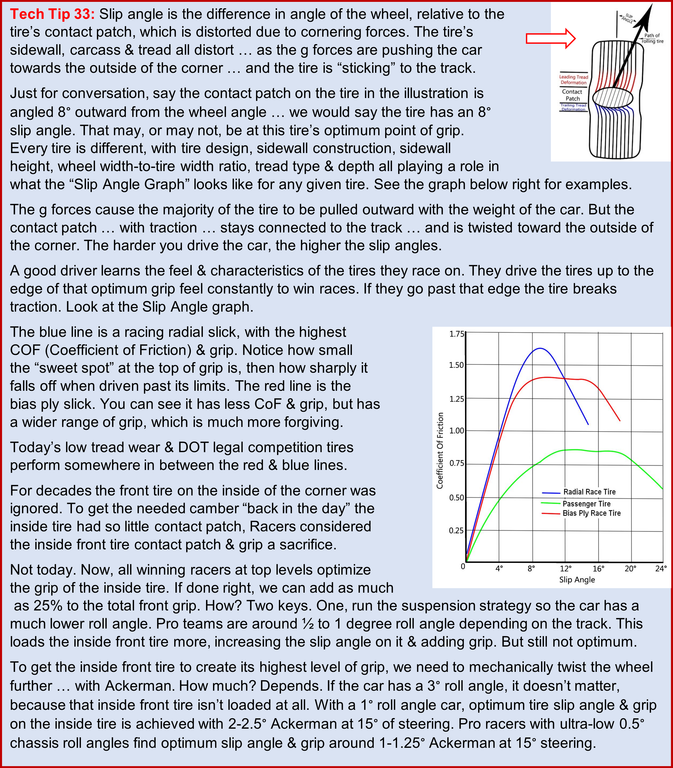

Sideforce is something you rarely hear about outside professional racing circles. But in all of pro racing, the aerodynamicists pay attention to sideforce as well as lift & downforce. What is it? Well ... it's aero force generated on the side of the race car, near the rear quarter panel. It is airflow pushing on a flat-ish surface, when the driver turns the race car into the corner at speed. The car is in yaw, relative to airflow, so there is more outflow on the outside of the car in this instance.

What does it do? This airflow pushing on the rear quarter panel is helping the race car to not pin out. It is like a hand providing a small amount of push on the rear quarter panel, at corner turn in. It was big in NASCAR back when they hand built bodies. They would make & massage the right side of the race car & specifically the rear quarter panel (fender) to catch airflow. They would do the opposite on the left side. See image of Cup car below. These were called "Twisted Sister" cars. Think of it as a small billboard out in the wind. They want it to catch side airflow as the car turns into the corner.

They would finess the door & lower rocker sheetmetal to help increase airflow onto the rear quarter. None of generated a ton of sideforce. But it mattered. If you didn't have it & your competitors did, they were beating you on corner entry & middle. Middle? Yes. Because if we can use 60-100# of sideforce to help the car not be loose on turn-in ... then we can mechanically free up the car to turn better in the middle.

I did the same thing with my NASCAR Modiifeds (see photo above). Al the Modifieds run flat side bodies, so nothing new. We just braced the right rear quarter so it didn't flex & lose the sideforce. We alos added a 4th spill plate runner in the middle of the spoiler. All those things add to help the race car have grip on corner entry. Again, there is a LOT more to learn in the Designing & Tuning Aerodynamics forum thread.

Bonus Tip: Grip Creates Harmonics

Grip creates harmonics. Period. Anytime we create more grip in a race car, we will have more harmonics. Higher spring rates? More harmonics. Higher sway bar rates? More harmonics. Stiffer valving to control the springs & bars? More harmonics. Shorter sidewall tires? More harmonics. Wider wheels & more tire pressure? More harmonics. Big aero creating downforce and load on those springs & tires? More harmonics.

Heck, extreme grip can be violent. Seriously. Ever watch a rear tire launch on a top fuel dragster? It is violent. Even in Pro/Stock & Pro/Mod doorslammers with 1000-3000HP, the launch can be violent. So much so it creates violent tire shake. I've personally seen drivers knocked unconscious from extreme tire shake. This is super high harmonics.

We get a high enough harmonics in road racing cars to experience tire chatter. I've seen it ... and felt it ... in front tires & rear tires. Where the tire is gripping ... letting go ... re-gripping ... letting go ... many times in a fraction of a second. That's road racing's version of tire shake. It is from grip harmonics. All grip create harmonics.

Ok. Ok. There are exceptions to the rule. Eliminating chassis bind reduces harmonics. So does eliminating stiction throughout the suspension. But, for the most part, creating race car with a high level of grip, brings a high level of harmonics with it.

This is not comfortable in the car. In fact, it is downright uncomfortable & will wear out the average driver in a shorter time. If the goal is to build a winning race car, the driver & crew need to embrace harmonics as a side effect of going faster. The driver needs to be in better shape & not complain about the harmonics to the crew. Because the only cure is to reduce grip & slow the car down.

Now, if you have a track car, and driving is all about fun, you need to decide what level of harmonics are you willing to live with in the car, to outrun all of your friends. Thank goodness track days only run 5-15 laps, then you get a break. But endurance racers, you need to decide how much grip do I need to win over my competitors, without wearing out the driver(s).

I'll close out this section & open it to questions on creating grip with a 4-page grip summary.

I'm a fan of bearing spacers & run them often in race car applications. These are adjustable for width & go in between two tapered roller bearings. They allow you to set the preload on the bearings without over torquing them. Frankly, the thrust load is already distributed to both bearings, regardless of running a bearing spacer. A spacer does not increase the thrust load capability of either bearing, so the small, weak outer bearing is still the weak link.

Bearing spacers allow the bearings to be fully tightened and yet have minimal preload & drag. So, they make the rolling friction less. Moreso on straights, because in corners, the bearings are still side loaded. Even with that side load, THE RACE CAR SLOWS DOWN LESS in the roll through zone with bearing spacers. Simply put, they "free up horsepower" by requiring less power to accelerate & achieve speed. We run them in between the rear floater hub bearings too.

This does reduce bearing temperature, which is a cause of a bearing failure. So, they also increase bearing life. it doesn't change the thrust load capacity of the hub bearings, so you still need to get the best ones that your budget allows. Would I suggest you run bearing spacers? Absolutely. They will "help" your bearing, by reducing the heat ... and they help your car by reducing rolling friction.

Bonus Tip #2: Not Grip Related > But Increasing Rolling Speed

I'm a fan of micro polishing gears & bearings. Why? So many key reasons:

1. They reduce the rolling friction

2. Therefore, they increase total speed possible

3. The race car slows down less in the roll through zone

4. Polished gears & bearings generate less heat & last longer

5. Polished gears are quieter

6. Polished gears do not require any "break-in" time or procedure

Bonus Tip #3: Not Grip Related > But Increasing Rolling Speed

I'm a fan of friction reducing coatings. Why? Lot of reasons:

1. They reduce the rolling friction, similar to bearing spacers & polished gears

2. Therefore, they increase total speed possible

3. The race car slows down less in the roll through zone

4. Friction Coated gears generate less heat & last longer

*The gears below are Moly Koted

Bonus Tip #4: Not Grip Related > But Increasing Rolling Speed

I'm a fan of ProBlend metal treatment. Why? A couple of reasons. If ... if ... if you don't spend the time & money to micro polish gears or have them coated for friction reduction, ProBlend metal treatment is the next best thing. ProBlend is an oil additive, but doesn't treat the oil. The oil is just the carrier of ProBlend to the metals. Once there, ProBlend treats the metal to have lower friction.

1. ProBlend additives reduce the rolling friction, similar to coatings & polished gears

2. ProBlend additives increase total speed possible

3. The race car slows down less in the roll through zone

4. Gears generate less heat & last longer with ProBlend additives

26. Suspension Bind

The most common mistake Racers make is not checking for suspension bind. Then the car handles bad at the track, usually in ways that don't make sense initially.

An autocross client had a professional shop install his new Speedtech front clip, front & rear suspension. It would drive "OK" at lower speeds, but when driven fast, all four tires would break away & drift. When he explained this, Ron told him the suspension is bound up. "No way. They were a Professional Shop" and other reasons were suggested. When he inspected it himself, all the suspension was bolted (impacted) into WAY too tight & bound up.

When he removed the coil-overs, the front control arm assemblies and the rear suspension would not move freely. This KILLS grip. Before your car leaves the shop, remove the wheels, coil-overs & one link on each sway bar. Each control arm assembly needs to freely move up & down throughout the useful travel range. The rear axle needs to go up & down, plus articulate freely. Then, with a helper, check it all with the sway bars attached.

Sway bars binding up is super common. We had a Racer run zero gap on each side of his splined sway bars front & rear. The car handled OK at lower speeds. But, at higher speeds & roll angle, the car lost total grip. News Flash: Sway bars (and torsion bars) get shorter as they twist. His sway bars were binding & shooting the rates to infinity. He added gap on each side & the car handled great.

Another client built his tube chassis car from scratch, but didn't check for suspension bind. He had sway bar linkage binding against the lower control arms. With a Monster 1-3/4" GT/NASCAR sway bar ... it literally broke the lower control arms ... under hard braking. Another sway bar bind situation I ran into was the racer was using typical bronze lined pillowblock bushings.

As you can see from the photo above, the bronze bushings are made for rotation of the sway bar, but side-to-side articulation. These work "OK" if you have zero flex in the chassis. But if the chassis flexes, they will bind up. That is eaxactly what this racer did. The solution is to pillow block bushings with a monoball in it to rotate any direction. See our Delrin monoball bushings below. They will allow the sway bar to operate bind free, regardless of any frame flex.

27. Chassis Flex

When you think about it, all chassis are rigid or flexible to some degree. No chassis is 100% rigid with zero flex, and if it is, you built it waaaaaaay too heavy. Rigidity in a chassis makes the car more responsive to driver input & tuning changes & creates more grip. Flexibility in a chassis makes the car less responsive to driver input & tuning changes ... and has less grip.

The lower grip is due to energy loss from the chassis flexing too much. I use an electrical analogy. Think about if we plug in a super heavy gage wire extension cord, going only 10'. It will not see very much amperage loss, if any. Now make that extension cord 100' & the amperage loss is measurable. Now replace that extension cord with a very small gage wire. The amperage loss will be huge. This is energy loss due to an inferior structure.

Race cars are the same. Most production cars are limp noodles & flex way too much. Some race cars are over designed & too rigid for their application. I've had cars that were too flexible. It was hard to make them fast due to their lack of grip. The flexy chassis just gave up too much grip to be fast. I've had race cars that were too rigid.

When I got into USAC Midget racing, I bought a used race car. I could see it was a more rigid design than others. Man, that thing was fast! For 10 laps. It was TOO SENSITIVE. As the track would rubber up on a 30-50 lap race, this car's handling would change significantly. We had to decide which 10 laps we wanted that car fastest. LOL

Our biggest competitor in the USAC Midget chassis business had a little trick up his sleeve. I could see the difference between his "House Car" & his customer cars. His cars had additional bracing to be more rigid. When I asked him about it, he grinned & said, "My customers are not constant tuners like you & I are. By making my customer cars softer, the car is less sensitive. It works OK at most tracks & track changes don't affect it as much. I make mine stiffer, which requires being more spot on the setup, but our car is faster."

Our 23 AutoX & Track-Warrior chassis vary in rigidity, depending upon how much power, tire, weight & g-force loads they're designed for ... and what is the priority ... a wide tuning widow -OR- every bit of lap time possible. It's not a one-size fits all. The same can be said for our 8 Race-Warrior chassis. They vary from each other based on power, tire, weight & g-force loads. All 4 of these chassis are designed for 700HP, but very different applications, different g-loads & different goals.

See the 4 chassis images below. The first one is called our AutoX-Ninja. Ninja because it's light & quick. It provides just enough rigidity for a 2600-2800# featherweight autocross car with 700HP. It has no place on a road course. It does NOT provide enough safety in my race car designer opinion. Nor does it have enough rigidity to handle road course g-forces.

The second image, right below here, is our AXT-Warrior, designed for double duty track days & autocross. Same frame. Much safer roll cage design for the higher speeds seen on road courses. This chassis is also designed for 700HP, but more rigid to handle road course level g-forces in the 1.7 range. Compare details.

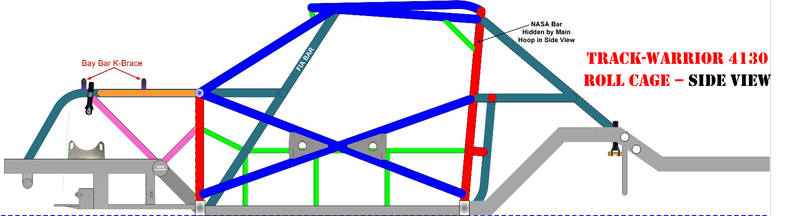

Compare the AXT-Warrior above to a Track-Warrior chassis below, designed to a full time track car or budget road race car with up to 700HP. The additions in structure are to make the Track-Warrior both faster & safer at g-loads near 2.0g. If all things were equal, weight, aero, power, etc. ... the Track-Warrior chassis will run faster lap times, but have a narrower tuning range than the AXT-Warrior.

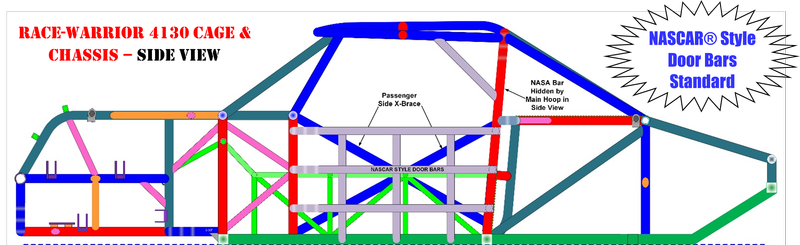

Now, below is a full blown Race-Warrior chassis, also meant for 700HP in top level road racing. Very different level of rigidity designed in. It is extremely stiff. Designed for loads well over 2g. This is meant for pro level road racing where every tenth of a second is precious. If all things were equal, weight, aero, power, etc. ... the Race-Warrior chassis will run faster lap times, but have a narrower tuning range than the Track-Warrior.

Summary: There is more detail & information on this area in the forum thread "suspension Strategies for Track & Racing." The key thing to know is if the chassis is too soft, too flexible, you will be giving up some grip. Conversely, if the chassis is too stiff, too rigid, it will have high grip, but in a narrow tuning range. Your goal is to have a race car chassis rigid enough to be fast & flexible enough to have a managable tuning sweet spot.

28. Aero Downforce

It feels kind of silly needing to talk about achieving grip with downforce in this section. So I'll keep it simple here & you can read in more depth & detail on how to do this in the "Designing & Tuning Aerodynamics" forum thread on this website.

Remember increasing front grip from aero downforce is just as important, if not more important, than the increasing rear grip with aero downforce. It's easier to get high amounts of additional grip on the rear tires by simply buying & installing a big ol wang or big spoiler. Easy peasy.

If you're not 100% clear on how spoilers work to create downforce, here it is. The spoiler itself is not where the downforce is. The spoiler just slows the airflow over the back of the race car to create a high pressure area in front of the spoiler. The trunk or decklid, as most call it. The flat area is where the downforce is created. The taller the spoiler and/or the steeper the angle of the spoiler defines how high the pressure area is.

The size of the usuable flat surface area plays a role in the rear downforce. The degree of high pressure & the amount of square inches of usuable surface area together define the actual rear downforce. So, a larger and/or flatter trunk or deck lid can create more downforce, if the high pressure created is the same.

The trunk/decklid needs to be strong enough to not flex away the downforce. Just like energy loss in chassis, springs & other areas, if the body panel the airflow is pushing on FLEXES, it is not going to be 100% efficient or effective. I've seen body panels flex up to 75 pounds before the chassis moved one iota. Nothing. That 75# of flex is 75# of downforce lost. So we need rigidity in the body panels we're creating downforce on.